The shape of things

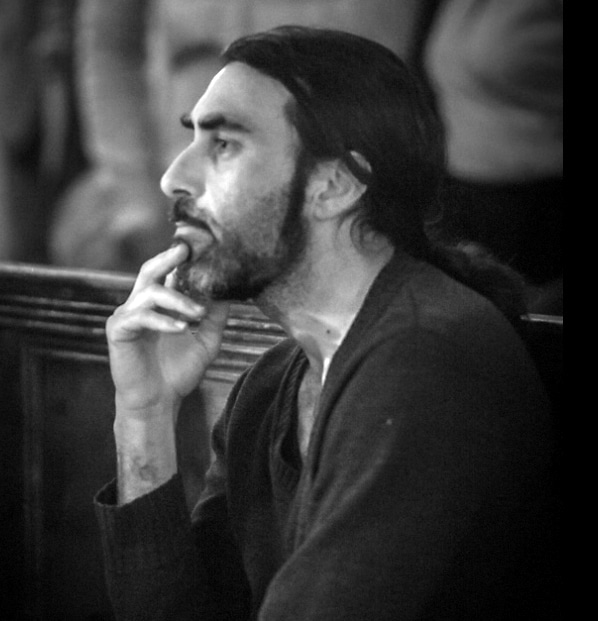

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

It is difficult for us to imagine how shocked – even scandalised – people were at the turn of the 20th century by the work of the so-called avant-garde of artists emerging in France at the time. Painters such as Picasso and Matisse and Cezanne and Gauguin before them impressed a new vision upon the age – one that placed subjective feeling above objective observation. Amongst sculptors Rodin and Claudel introduced a torrent of subjective feeling, whilst Brancusi sought subjective essence in abstraction, and Maillol and Marini a simplified monumentality in figuration. Modernism broke all the codes of the academy. Representational sculpture subjectively morphed, blooming into the monumental figures of Henry Moore and crumbling into the shadowy figures of Alberto Giacometti.

The work of contemporary Irish sculptor Michael Quane is born of the monumental tradition of modernist sculpture, in the line of Marini and Moore; for although relatively small in scale his sculptures exhibit a similar dedication to mass and proportional distortion (in Quane’s case oversized hands and feet), ‘formed through feeling’ rather than observation.

Quane’s career, like his modernist antecedent, Marino Marini, has almost been entirely devoted to the horse and rider motif, the horse in recent years morphing into unidentifiable “strange beasts”. His figures – again like Marini’s – are anti-classical, non-heroic, ordinary, even squat, an obvious distinction from classical equestrian sculpture (think of Michaelangelo and DaVinci). Where, however, Marini morphed his figures more and more into ‘primitive’ lines of energy, Quane’s figures have maintained their voluptuous curves and spherical mass, often entwining with and morphing into the beasts they ride.

Quane’s principle medium is stone, and his method, direct carving. He has often, in interviews and talks, remarked with genuine awe on the sheer age of the stone he works with (for example 350-million-year-old Kilkenny limestone) and feels a deep connection with the geological life of the earth. Concurrent with this awe of age and history is a reverence for the force of gravity, which he describes as “the God force, the organiser”, that which holds the universe together. It is a sculptor’s reverence for every consideration of mass, he explains, is contingent on gravity’s force. But it is also a source, for Quane, of light-hearted levity, particularly in relation to his ‘Buoyed’ series of swimming figures, where he plays upon the dichotomy of weight and weightlessness, of body and spirit.

I have discussed in previous articles, the importance of the spiral in two-dimensional composition, but it is of course also instrumental in sculpture. In so saying, circularity is a key aspect of Quane’s ‘beast and rider’ forms, perhaps best demonstrated by his work titled ‘Aqualung Buoyancy’, from 2003-2020.

In this work an aquatic rider sits atop a dugong-like creature, the rider’s oxygen tank seeming to morph with the creature’s tail, whilst the rider’s breathing apparatus seems to morph into the creature’s head. The connectedness of all life is given tactile expression in the circular essence of the form, whilst concerns of ‘natural’ and ‘man-made’ are leveled by the material of the stone. It is a wonderful image – playful and soft, heavy yet buoyant, two yet one.

We see this circularity born out in a different way in the work ‘Strange Beasts’ (2020), the title piece of Quane’s show, held in the Lavitt Gallery, Cork, last year. In this piece, carved from limestone, the right foot of the rider forms the fulcrum of an invisible spiral which leads up and around his body, arcs down, around the head of the beast, circling back through the opposing thrust of the beast’s legs and body. The rear thrust of the beast strikes a wonderful tension with the forward-tilt of the rider, underscoring the precarious position of the latter, and yielding a sensation of unlikely balance, a feeling of imminent collapse countered by remarkable stability. The art of pushing such tensions to their limits is the very essence and language of sculpture, a language of which Quane is clearly a master.

Speaking of the beast and rider aspect of his work, Quane explains that “it is like a palette for me, I keep coming back to it. It’s a barometer, it tells me how I am, both in life and in work.” Within the limits of this theme Quane has, like Marini before him, found a universe of expression, one that, happily for us, keeps on giving.