I live on the edge of the River Ilen where the river is still tidal. Every so often I walk along the river’s edge collecting waste plastic, glass bottles and tins or aluminium cans that have washed up along the shore line.

I put it in plastic bags and phone the council who send someone to come and collect it and take it to a municipal site. I go home, have a cup of tea and feel a mix of righteousness, sadness and frustration, because I know that on the next high tide more rubbish will get dumped on the edge of the river and more rubbish from the edge of the river will re-enter the waterways.

Sadly, research shows that most of what I pick up will either go to landfill or end up back in the water on some far-flung shore.

Tins, bottles and plastic need to be clean if they are to be to be recycled. If the plastic I pick up is not clean, it will contaminate the recycling stream. If I mix recyclable plastic with non-recyclable plastic, I will contaminate the recycling stream.

According to figures from Repak: In Ireland, 100,000 tonnes of contaminated recyclable material is sent to landfill each year, causing considerable damage to the environment. Repak estimates that each person in Ireland generates 61 kg of plastic packaging waste per year. Too much of that ends up in the ocean.

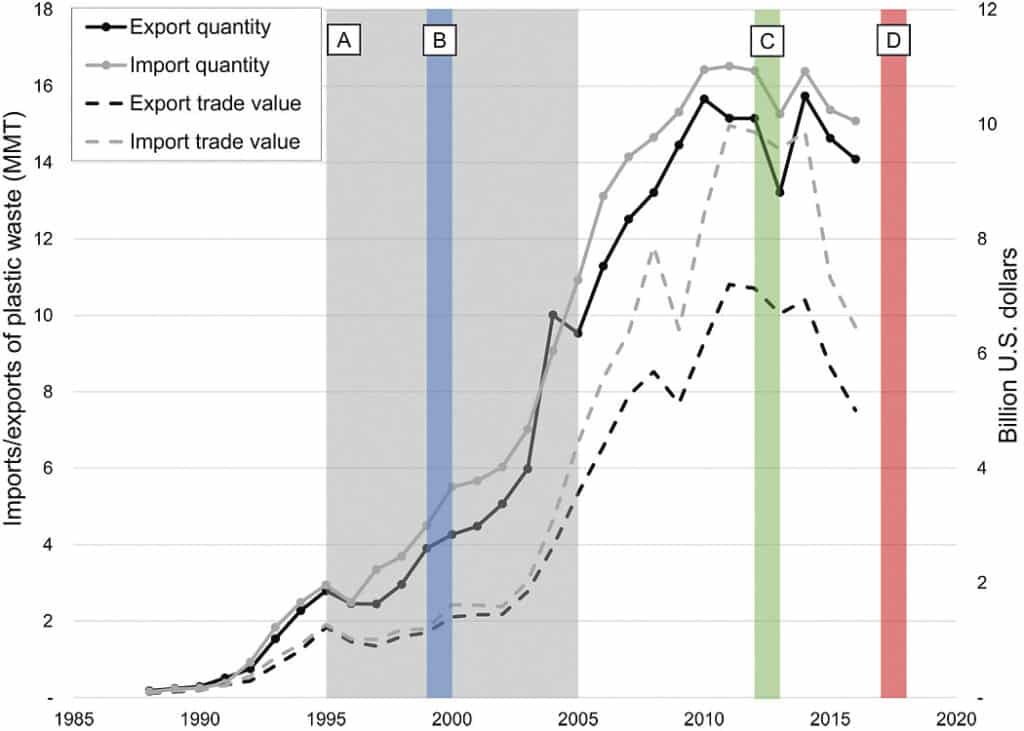

Government policy to improve the environment has consistently encouraged recycling, however the material that is sent for recycling is mostly shipped to Asia. Indeed, waste plastic has become an important mainstream trade. Global annual imports and exports of plastic waste have been rapidly increasing since 1993. In 2016 alone, about half of all plastic waste intended for recycling was exported, with China taking most of it.

Collectively, China and Hong Kong have imported 72.4 per cent of all plastic waste. Hong Kong acts as an entry port into China, with most of the plastic waste that has been imported to Hong Kong (63pc) also going directly to China as an export. Out of all plastic waste imported into Asia, only about 20 per cent is recyclable. This 20 per cent is removed and traded whilst the other 80 per cent is dumped into landfill or the riverbanks and finishes up in the ocean.

Most of the plastic that I pick up from the banks of the river, in an effort to stop it entering the oceans, makes an expensive journey across the world and ends up in the ocean; because we simply give our waste problem to other countries; who just like us, do not really have the resources to deal effectively with it.

In 2013, the Chinese Green Fence campaign saw intensive inspections by China of incoming loads of waste material, in an effort to enforce import regulations.

This resulted in a reduction of plastic waste accepted at the Chinese border, with some shipments being turned away and sent back to the source countries.

As China tightened up it’s laws and refused to accept much of the West’s plastic waste, other countries followed with Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam bringing in restrictions in 2018.

January 1, 2021 saw the new legislation making shipping of mixed plastics from Europe to underdeveloped countries illegal.

Data from Eurostat shows that Ireland produces the highest volume of plastic waste per person in the EU. This leaves us with a significant problem.

Nik Spencer of Mission Resources states: “The issue of protecting our environment from our own ‘waste’ is critical. The continuing action of discarding material with no further purpose, to the well evidenced and documented broken ‘waste’ system in the blind faith it is not causing harm to the environment, must be significantly reduced with haste, to avoid untold environmental and human health issues.

This requires a Paradigm Shift in our way of thinking, driven by Life Cycle Assessment.”

The paradigm shift Nik is talking about is to stop thinking of ‘waste’ and instead call it ‘resource’.

His view is that every home and every business should manage this valuable resource at source, cutting out the need for expensive transport to central collection areas and redistribution.

Nik’s solution is slow pyrolysis, using the resource in individual waste-to-energy plants connected to a boiler, hot water tank and your drain. You open the device’s lid, put in your rubbish, which can be anything from spoiled food to grass cuttings to used nappies and plastic packaging. Close the lid. Press the start button. Walk away.

His company has created My HERU (home energy recycling unit), a heat pump run on the very materials that we no longer want and have such a problem getting rid of.

Nik says all materials’ lifecycles should be examined so that at the end of their lifecycle there should be nothing that could damage the environment. He describes pyrolysis as the speeding up of a natural process. “Bury a dinosaur or a tree in the earth in a lack of oxygen” he told me “and wait for millions of years whilst the heat from the earth transforms it into hydrocarbons. HERU does exactly that process but speeds it up.”

Using HERU produces a very small amount of oily vapour that passes over the heat exchangers and condenses. The oil content is washed off the heat exchangers and along with any chlorine flushed down the drain. Removing the chlorine before the combustion stage avoids dangerous dioxins being produced. The combustion stage produces syngas which is scrubbed through a water screen filter, passes through a cyclone to spin off the moisture, through a compressor, and thence directed to a storage tank until it’s needed by your boiler.

All that is left is ash containing a gritty substance called lye. The final stage involves the HERU pressure-washing its own innards to flush the ash down the drain. Lye helps clean the sewers and because it is alkaline it helps neutralise the sulphuric acid drained to sewers by modern boilers. This sulphuric acid inhibits the bacteria used in water treatment plants, so neutralising it is helpful to the water companies.

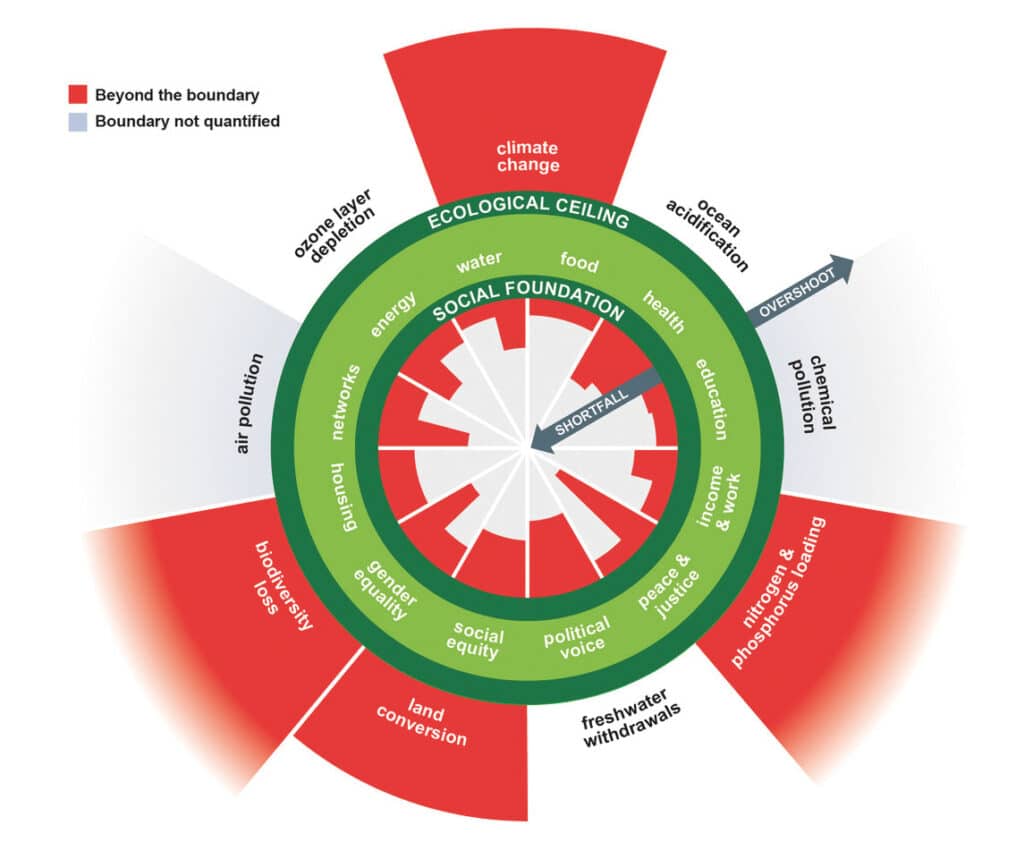

We urgently need to find elegant solutions to our environmental problems.

However, we not only need technological solutions and community efforts but we also need the political will to respond to those technological solutions, creating policy that supports them and puts them within reach by using subsidies and grants. We need policy that allows communities to choose a regenerative future and works on clearing up our unsustainable past.

Stop thinking ‘waste’ start thinking ‘resource’.

Find more about HERU at www.myheru.com.