The shape of things

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

One of the most remarkable processions of recent years in West Cork was the first Samhain festival in Clonakilty in 2017: to the beat of drums fantastic masked figures with long gilded trumpets loomed out of the dusk and the mist into the yellow haloed lights of Wolfe Tone Street. Others with Venetian-inspired curlew masks beat the drums, whilst a head-wreathed choir, faces painted and bodies gowned in cerebral white, sung and chanted into the liminal spaces that divide the living world from the dead. It was a well-spring of theatrical animism which struck a primal chord; the sense of release whilst under the cover of processional theatre was palpable. The masks, the animal cries and the music gave licence to an alteration of reality which was as unexpected as it was magical.

There are certain paintings which recall this sensation of the mask looming out of the void, where the paint appears ecstatically dripped, scraped or slung against the darkness. One such is Rembrandt’s ‘Self Portrait as Zeuxis Laughing’ (1662). In the theatre of paint this was the Dutch master’s swan song, his visceral laughter-through-paint in the face of ruin. There is a devil-may-care attitude to the figure which comes through its wild, spontaneous, visceral application. The drawing is there, the visage of the Master unmistakeable, but he was not being precious; he was in full, poetic flight, slamming red and gold against the darkness, daring the promise of death to diminish him.

Rembrandt eschewed colour in his self portrait as Zeuxis (it is a monochrome of yellows, from ochre to cadmium) and in doing so distanced the work from the mimetic surface of reality, embracing instead something deeper, something closer to the rawness of spirit. He was, at this latter stage of his life (he was to die seven years later) down on his luck, bankrupt and deserted by buyers who had turned away from his thick, edgy application for something more classical, safe and serene. It was perhaps for this reason that he embraced the subject of the classical painter Zeuxis who, as legend has it, laughed himself to death after painting a portrait of an old woman who had commissioned him to paint her as Aphrodite, the goddess of love.

Rembrandt used Zeuxis as a mask, stripped his palette bare, and shone. Many of the self portraits by the contemporary Norwegian master Odd Nerdum shine in a similar away, the painter’s rugged fluency allowing shadowed areas to seemingly float on the raw ground of the imprimatura. It is his strangely titled ‘Hepatitus’ from 1996, however, which feels closest in feeling to Rembrandt’s ‘Zeuxis’, the reds and golds of the figure laughing against the darkness. A close-up of the head reveals Nerdrum’s splendid semi-abrasive delivery, the true solidity of the monochromatic form belied by the schism of darting strokes and abrasive distortions, the paint in flux, even as it is fixed, the expression alive even when frozen.

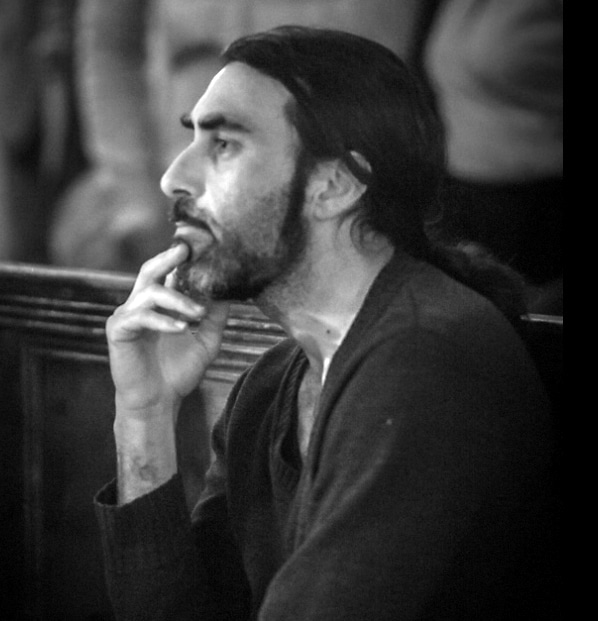

Against these two painterly masks, I would like to pitch Konstantinos Kyrtis’ powerful work, ‘Cecco d’Ascoli’ (2021). Kyrtis, a celebrated portraitist from Cyprus bares in his work all the hallmarks of late Rembrandt, from his pared-back palette to his visceral, deeply felt application. ‘Cecco d’Ascoli’ is no exception. Like Rembrandt’s ‘Zeuxis’ its subject is taken from the distant past; Cecco d’Ascoli (c. 1269–1327) was the diminutive used by the Italian writer and poet Francesco Stabili who was burnt at the stake as a relapsed heretic (Oxford Bibliographies). Like in the work of Rembrandt and Nerdrum the skin of the paint flurries against the darkness, its visceral body alternately protruding from and dissolving into the canvas. The ecstatic indeterminancy of the boundary between the figure and the void, combined with the figure’s melancholy expression gives this painting a great and powerful poignancy. It is a painterly mask of the distant dead, imagined into an oily spell which hovers between being and non-being, the liminal space of genuine art.

Kyrtis (b. 1974) often draws his thematic material from classical myth, sculpture and writing. He channels classical comedies, such as ‘the Birds’ by Aristophanes, conjures the tragic figure of the Joker, the poignancy of the marionetist and the mask-maker. His rich, powerful paintings dance with the idea of ‘commedia dell arte’, the comedy of art, seen as with Rembrandt and Nerdrum, through a tragic lens. Ironically there is no laughter in Kyrtis’ paintings; they are ever sombre and deep.

A painting of a figure surrounded by Venetian masks from 2014 reminds me once more of the Samhain festival of 2017 and the curlew masks worn by the drummers. From painting to procession, from the painted face to the face-painted choir, the liminal masquerade of art draws us to endings and new beginnings and suspends us magically in the spaces between.