The shape of things

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

Having recently lost a very dear friend who was also my mentor and guide as a painter, the subject of funerary portraiture, and portraiture in general, has been on my mind. The instinctive desire to remember the other’s face, to conjure an echo of their presence, whether it be in stone, mosaic, encaustic, tempera, pencil, ink or oil is as old as Greater Roman Syria, and probably older still.

Whilst the pharaonic caskets of ancient Egypt were painted with a stylised likeness of their deified occupants, it was not until the first century B.C. that the fleshy, realistic looking Fayuum mummy portraits of Roman Egypt first started to appear. Many of these encaustic paintings (where wax is the vehicle of the pigment) have come down to us, and via conquest, plunder, trade and transaction have made their way into many of the major museums around the world. Their typically large eyes look calmly out at us, across 2000 years of history; some radiate soul and seem to deeply question the beholder, others radiate youthfulness, intelligence, gentleness and beauty. Still others appear inscrutable or incisive, the male faces variously bearded and smooth, the females elaborately adorned with earrings, necklaces of pearl and fashionable hair styles. None are old. Whoever they were they were clearly wealthy and could afford to be remembered, their highly individual visages painted on wood and embedded onto their caskets or wrapped over their mummified selves.

The funerary mummy portrait is a far cry from the painted portraiture that we are accustomed to, and still further from the ubiquitous iphone selfies and holiday snaps which reign supreme on our devices. Today we take a likeness for granted; it appears effortlessly without thought or presence, and we multiply visages of ourselves and each other endlessly, the images easy yet still conjuring all the emotions of remembrance that we instinctively long for.

Stepping into the painter’s studio, however, we find that a drawn and painted likeness can be a fickle thing. While one aspect may ring true, another part of the face may elude the conjurer; the likeness appears and disappears, seems too old or too young, is too stiff or too loose, is missing that indefinable ‘something’. And then, as if by magic, it appears, the presence held insolubly in oil; a soft miracle which combines the energy of the artist’s hand with the presence of the one beheld. This combination is what makes a painted portrait so mysterious; it is the trace not only of the person who is beheld, but also of the artist who forges the image.

This mysterious transaction is why drawing and painting from life always has an edginess and liveliness that painting from a photograph can (though not necessarily) lack. The live encounter, limited by time, informed by the presence and needs of both artist and sitter encourages a painterly gesture that lives in the moment, that is a record of the moment, and which resists the ‘tyranny of perfection’ that is ingrained in the photographic medium.

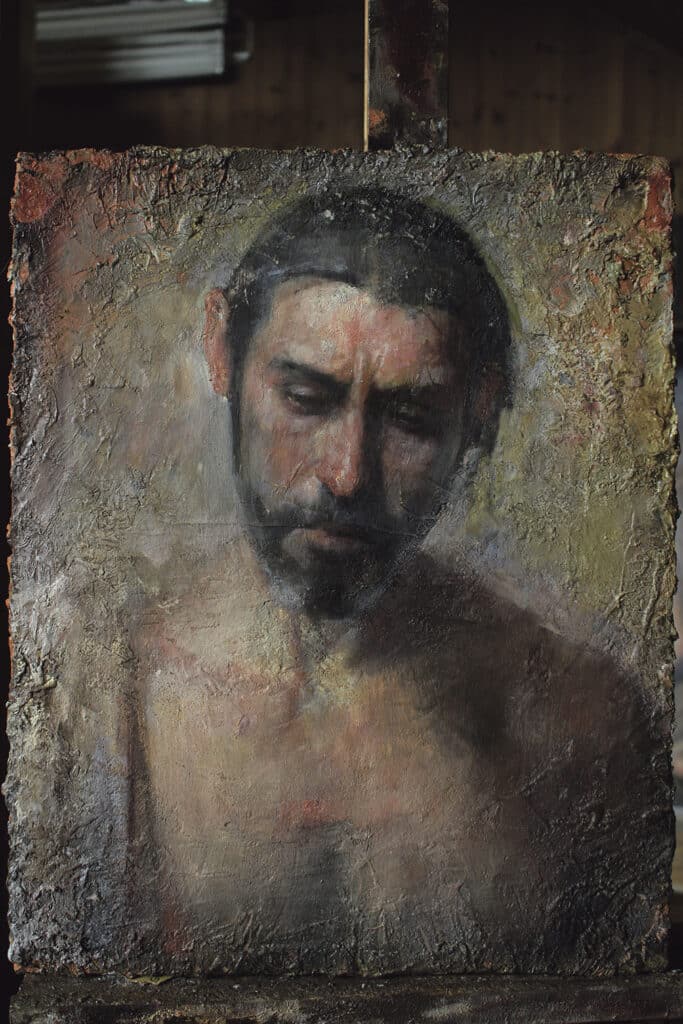

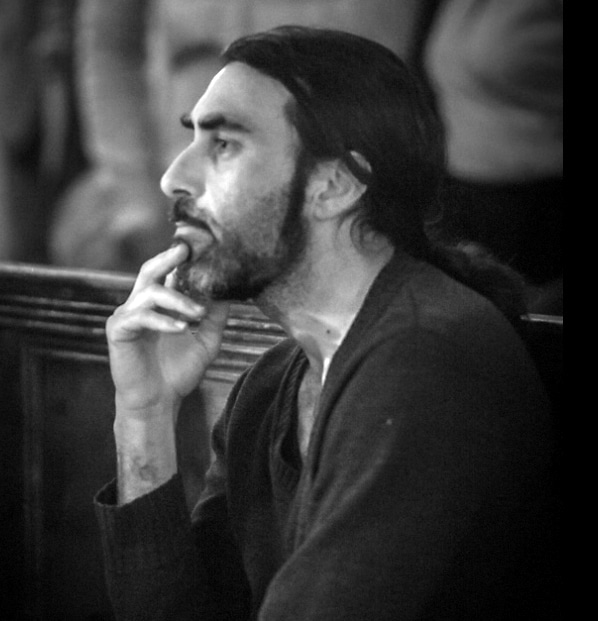

Because of all the variables no two transactions between artist and sitter will ever be the same. As a student of the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum in the summer of 2017, I was asked to sit outside, in the early evening light for a portrait study. Odd had decided that I would make a good ‘Christ’. It was the first of nine or ten sessions held over the course of six weeks, and after each session there was a discernible shift in structure, mood and psychology. It is an incredibly perceptive painting and a deeply truthful likeness; an accretion, let us say, of nine or ten variants. But it is also unmistakably a Nerdrum, with all his attendant textures, accretions, abrasions and gestures. It is full of life because it is full of encounter.

Presumably the nobles of Roman Egypt, whose visages have come down to us, commissioned their funerary portraits whilst amongst the living. We will never know how close to a true likeness the commissioned painters came, though presumably they must have been close enough to have been accepted by the client. What we do know is what we can experience by looking at these portraits: that is the depth of the gaze that looks out at us, either at us, or just past us. That gaze is the trace of a unique encounter, and that in itself is incredibly moving.

My friend and mentor (not Odd Nerdrum) left behind many great paintings and many great portraits, not least those of his mother, painted from life in her nursing home. They are an enduring testament, not only of a son’s love and his continual act of encounter with his mother, but also of a great mastery of oil and the humility and grace to invite the presence of the other to dwell within it. Rest in peace, R.K.B.