Clonakilty-based painter James Waller reflects on his experiences of Christmas imagery – from his childhood in Western Australia, through the art galleries and churches of Europe, to a treasure in a small church in West Cork.

As a child my Christmases were spent in the baking hot environs of Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, a gold mining town on the edge of the Nullabor Plain. Images of snow encrusted sleighs and heavily-coated Santas collided with both the image of the Three Wise Men crossing the desert to greet the baby Jesus, and the 35 degree air outside. Even to a child these collisions were bizarre.

Still, Christmas meant images of snow, reindeer and stars (in the outback we had the latter in abundance) as well as chimneys (what were they?), Christmas trees and presents, as well as films and cartoons relaying stories from snow-bound England and America. The hypnotic power of film, especially, far outweighed the peculiar dress-ups of school nativity plays or the religious spectacle of kitschly painted sculptures.

Clearly the power of film, popular fiction and fantasy has long eclipsed the silent world of history and painting and the image of Christmas has been shaped accordingly. Charles Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol’, is etched into our Christmas DNA, courtesy of its many filmed, animated and staged adaptations. The image of Ebenezer Scrooge, hunched over his accounts, proclaims Christmas far more loudly than, say, Rembrandt’s ‘The Holy Family’ of 1646.

Images are powerful and engrave themselves into our emotional landscape. As we tie them to our own Christmas experiences they become emblems of nostalgia as much as wonder. It is strange to say, but I am nostalgic for the snow I never knew, nostalgic for the innocence, which found wonder in the stars and the glint of – ‘was that ‘his’ sleigh?’

It is ironic, therefore, to have discovered the many masterpieces of painting that dealt with the infant Jesus – not through my experience of Christmas, but through many journeys as an adult, both through art books, and the great art museums of the world.

A great example is Da Vinci’s ‘Virgin and Child with St Anne and John the Baptist’ (known as the Da Vinci Cartoon). Mary appears to sit on the lap of St Anne as she holds Jesus aloft. St Anne gazes at Mary with an infinite tenderness which seems to swell and clang like an ocean bell. It is extraordinary to see it in its alcove in the National Gallery of London, all shadowy silence and eternal togetherness. But I have never linked it to Christmas.

As one delves deeper into the history of pre-film and fiction Christmas imagery the riches grow, as do the ethnic and geographic variations of the Christmas story. Hence the dark Judean infant becomes, under Leonardo da Vinci’s hand, a light Italian cherub, Mary and St Anne, searing Italian beauties (‘The Da Vinci Cartoon, London’). Bethlehem is also transformed, under the brush of Pieter Breughel the Elder, into a snow-encrusted landscape, in his painting titled ‘The Census at Bethlehem’ (1566).

Mary and Jesus morph yet again into a Dutch mother and infant in Rembrandt’s ‘The Holy Family’ of 1646. The dark Rembrandtian interior comes complete with a tromp l’oeil frame and red velvet curtain (tromp l’oeil means something painted to look like a three dimensional fixture or architectural element). A fantasy of course, but for Rembrandt it was a beautiful device to reveal the painterly stage and the ‘actors’ upon it.

Our readiness and ability to assimilate differing image-variants of the same story is the same ability we employ when watching theatre or film. In theatre it is aptly called ‘the suspension of disbelief’.

We suspend our disbelief when we gaze at Breughel’s winter landscape, depicting a wintry Dutch Bethlehem. Even though we know the ‘real’ Bethlehem as a desert town, the fusion of its story with a Dutch winter is somehow spellbinding. And for those for whom snow is the reality of Christmastime it literally brings the story home.

Equally, with Rembrandt our knowledge of the narrative of his ‘Holy Family’ is given eternal and familiar resonance through his signature golden light, deep chiaroscuro (intense dark and light), and use of Dutch models. We accept immediately the ruse of a Dutch Jesus, just as we do an Italian, German or Spanish one. The adaptations bring the story closer to home, make it relatable, less historical and more universal.

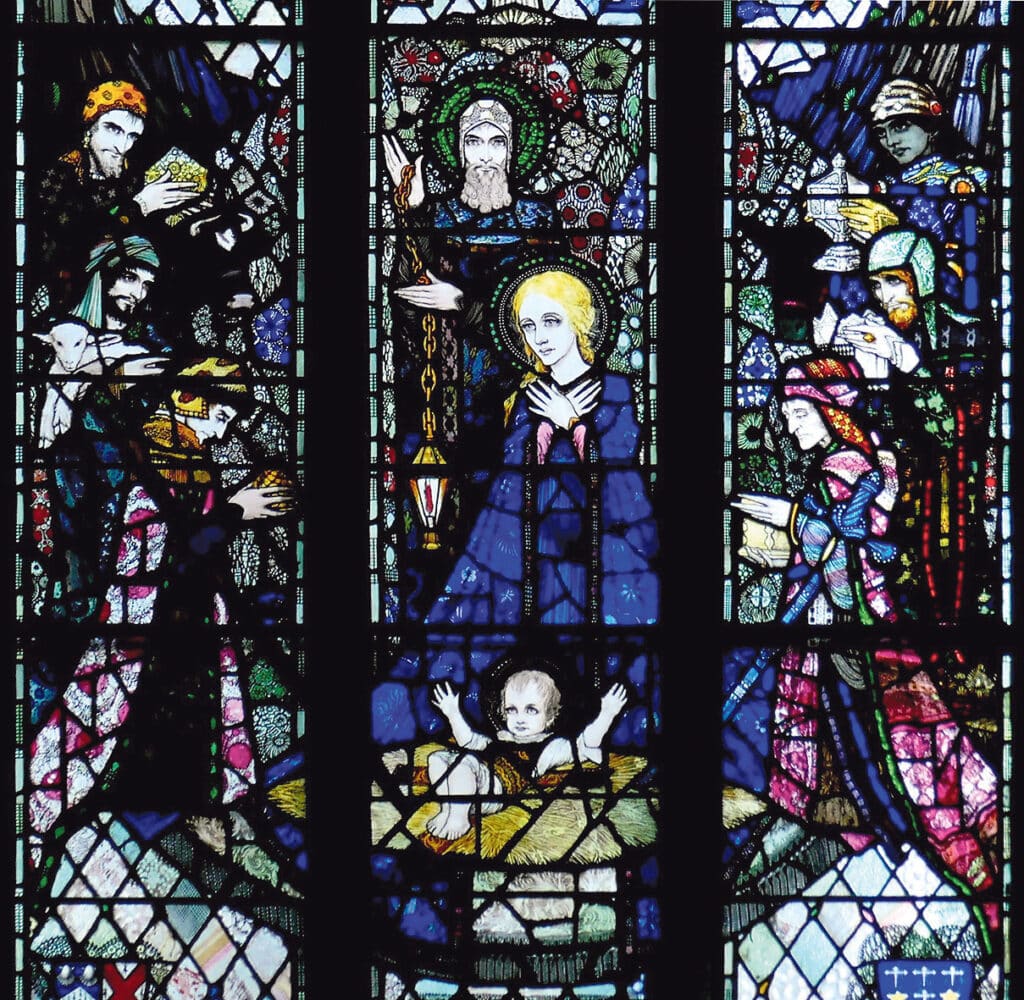

In St Barrahane’s church, Castletownsend, locals can find their own very Irish image-variation of the Christmas story: Harry Clarke’s stained glass Nativity window from 1918. In this wonderful image the devilishly good-looking Holy Family is flanked by dark, pale and red-bearded shepherds and Magi; the regal Joseph holds forth a lantern and looks for all the world like a Russian Czar; the sharp-eyed Magi and shepherds are interchangeable but for a lamb here and a treasure there; and Mary and her child are pale-faced innocence personified. All are bejeweled and encrusted in Clarke’s hallmark ornamentation, his colours glinting darkly in the cool church of St Barrahane.

The Christmas image has been made and re-made a thousand times, crossing all ethnic and geographic boundaries. Its success has been in its adaptability, and in our ability to, in theatrical terms, ‘suspend our disbelief’. It is in this realm of suspension that we experience the magic of art. Peeling back some of the popular layers of imagery we can find treasures we might not have seen before and thus renew our love of the season.