I knew very little about West Cork, or my links to it, until I was an adult. My dad had mentioned our family coming from there but didn’t say much more than that. Instead, my personal relationship with West Cork started by accident, in the summer of 1988 on holiday in Spain of all places, where we befriended some chaps from Cork City writes Paul O’Neill.

As our holiday in Spain drew to an end, one of the Cork chaps jotted down his address and insisted that we visit him. My friend Iain and I had been talking for some time about visiting Ireland and this was the spur we needed; so in September of that year we set off in my ancient yellow Opel car for a week’s holiday in Ireland.

After a night in Dublin, we headed southwest, sleeping in the car due to lack of funds. We stopped off at Carrick-on-Suir in Tipperary to visit the hometown of our biggest hero, cyclist Sean Kelly, and then made our way on to Cork City, where we ended up getting lost trying to find our new friend’s house, so instead we headed straight for Dunmanway.

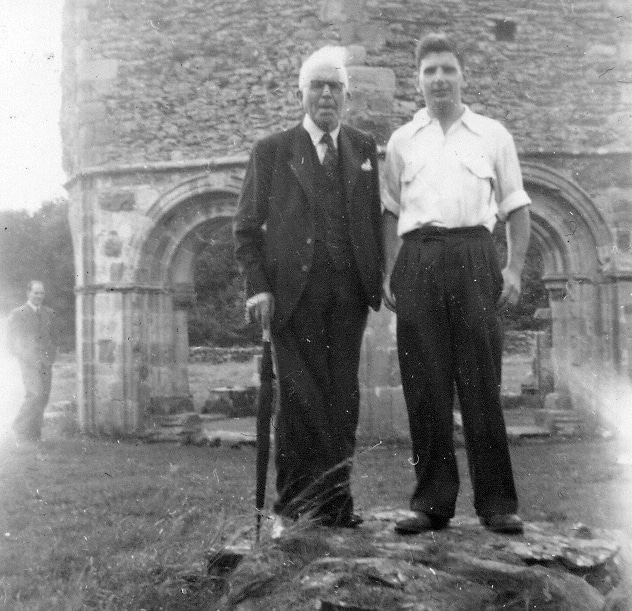

At this point in my tale however, we have to back up a few years, rather a lot of years in fact, to 1882. That was the year in which my paternal grandfather Paul O’Neill, after whom I was named, was born into a farming family in Reenroe, near Clonakilty, West Cork. I never knew him, as he died in 1956, more than a decade before I was born. Paul had moved to Scotland around the turn of the 20th century, working in the mining industry in the Glasgow area, becoming a slag-crushing plant foreman and then manager. He cuts an impressive figure, always immaculately well-dressed – every photograph shows him wearing a suit and tie, even in one where he’s relaxing at home. He must have also been tough and smart though – being an Irish Catholic immigrant in the west of Scotland back then may not have been easy; and he might well have faced a measure of prejudice, but must have gained the respect of both his colleagues and superiors in order to achieve such a position of authority. He married my Scottish grandmother quite late in life for those days (aged 42) and they had four children. My father Dennis, the only boy, was born in Glasgow in 1925.

Meanwhile, our West Cork family appears to have drifted towards Dunmanway, with several of them living and working in the town. There were still very strong family links between my immediate family in Glasgow and our relations in West Cork when, in 1946, my dad, with a few friends and fellow members of St. Christopher’s Cycling Club pedalled all the way from Glasgow to Dunmanway. This might seem to most of us now like a monumental feat, but trips of this nature were quite commonplace back then. Driven by a sense of adventure, many people spent their holidays cycling and youth hostelling around the UK and Ireland. Dad’s trip was strategically planned to allow him to visit family, but when we were planning our trip 42 years later, he couldn’t tell me anything about his remaining West Cork family, having lost contact many years since.

He seemed keen for us to go, and thought it possible that there would be some of our relations in or around Dunmanway but had no useful information. Although disheartened by our Cork City shenanigans, Iain and I were curious, and at a loss for anything else to do, we motored west.

Dunmanway then was much more like a sleepy village than the busy town it has since become, and it didn’t take very long to explore. We started at the east end of Main Street, looking for evidence of O’Neills and found an encouraging number of businesses operating under that name. The shops had all shut for the day, but O’Neill’s Pub/Undertakers was open and we stopped in for a pint and to ask if they were ‘our O’Neills’.

Family businesses that became pubs in the evening seemed to be quite common in Ireland back then, but this was a particularly odd setup. They used the waiting/reception area as the pub, and to get to the toilet, you went through a curtain and down some steps, into the showroom where the coffins were displayed. They were empty (I assume) but that didn’t much diminish the eeriness. As you supped your beer in the waiting area, it felt like you were waiting to occupy one of those boxes. Anyway, it turned out that those O’Neills were not related to us, so we left and carried on along Main St.

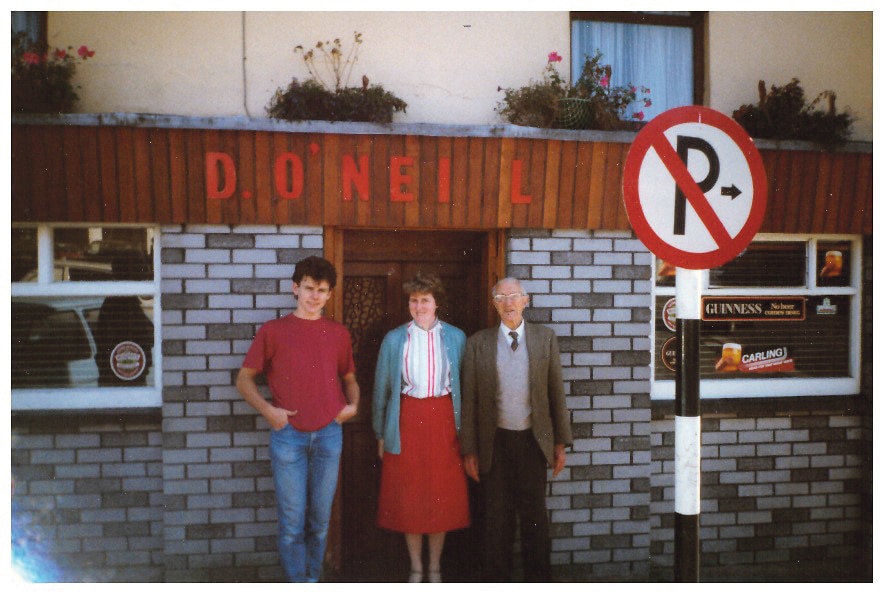

In The Square, we came across D. O’Neill’s pub on the corner (later Nealums). By this time, I was getting weary of asking about my family, as we had managed to confuse quite a few people without actually learning anything and I was ready just to enjoy my beer without interrogating the locals. Iain was on a mission though and, frustrated by my reticence, marched up to the lady who was serving and related my tale while I tried to hide in the corner. The lady (Margaret) listened politely and then, without speaking, turned and went into the back. We were concerned at this point that we’d done something wrong and imagined being forcibly ejected by a hefty staff member. Instead, she emerged a few minutes later with an elderly gentleman, her father Denis O’Neill, who turned out to be my Dad’s first cousin. He remembered Dad and the cycling club visit and had known my grandfather. Thank heavens for Iain and his big mouth.

Instantaneously, we went from being strangers in a faraway place to being welcomed like long-lost family, which I was, but Iain’s welcome was just as warm. The other five or six customers were treated to a free drink in our honour, which made us very popular.

The night thereafter is a bit hazy now, what with the passage of time and so much to take in (not to mention all the beer). The only customer I remember with any clarity was big Tim, a giant of a farmer, with hands like steam shovels and a hydraulic handshake. He smoked Capstan Full Strength cigarettes, forced one on Iain and laughed uproariously at the inevitable coughing fit that ensued – I was spared thankfully, as I don’t smoke. Tim’s habitual way of relaxing was to prop himself on a barstool several feet away from the bar and lean – more-or-less horizontally – across the sizeable gap, with just the tip of his elbow resting on the bar for support, forming a sort of bridge between stool and bar. An impressive feat of human engineering!

We had a wonderful evening and were not allowed to pay for any drinks, though we had absolutely no idea how much we consumed as they just kept topping up our glasses. We left in a somewhat wobbly state, but I will never forget the lovely Irish welcome and the kindness and hospitality of Margaret and Denis. However, they were not finished with us and invited us back for lunch the next day.

Not a little hungover, we arrived at the allotted time and were treated to a mountain of roast beef, potatoes and vegetables with creamy Guinness to wash it all down. Welcome fare for two impoverished and hungry travellers. Denis then took us out and about. Our first stop was Michael Collins’ TV and bike shop, back along Main Street. From there, Michael, being another of my Dad’s cousins, joined us for the next leg. As we headed for the car, Iain and I walked as slowly as we could manage but still had to stop often and wait a very long time for Denis and Michael to catch up. It wasn’t that they were frail; it was more that they lived life at a much slower pace than us city types. They also stopped to chat with absolutely everyone they met. It was a remarkable and delightful snapshot of Dunmanway from a bygone era.

Our next stop was the farm at Reenroe, Clonakilty where my grandfather was born. At that time, it was in the hands of another of my Dad’s cousins and his wife where another warm welcome awaited us (although I’m thoroughly ashamed to say that I forget their names). Their farmhouse was built in the 1950s, if memory serves, but the remains of the original farm cottage, the one in which my grandfather was born, were only a few hundred yards away, although it was just an overgrown pile of rubble at that time. We felt like royalty when our hosts dusted off some antique-looking bottles of Guinness for us, and we were then regaled with memories of days gone by. They all talked about my grandfather, recalling him as a person they knew well and loved, but also remembering his prowess as a horseman, and we were shown a photo of him jumping over a rather high-looking farm wall on a horse. I wish I remembered more about that visit, but I was young then, a bit bewildered by the tsunami of family history, and things that didn’t seem all that important then feel like the most vital of details now. Being in the same room as those four people was very special.

We stayed a couple of hours, then dropped Michael back at his shop and said goodbye, but our day was by no means finished, as Denis was very keen for us to see an essential totem in our family history, the Kilmichael monument. In Glasgow, where we grew up, the IRA was taboo, mainly due to the ongoing troubles in N. Ireland. You’d see it graffitied on walls and sometimes hear IRA songs at football matches but it was well known to all that its mere mention could land you in serious trouble. Imagine our surprise then, when we were taken to this massive monument with ‘Irish Republican Army’ engraved on it. I remember, much to my embarrassment, looking around uneasily to make sure no one was there to see us, as we’d get reported, or something.

On the very spot where one of the most important engagements of the Irish War of Independence took place, Denis, swelling with pride, told the gripping story of the boys of Kilmichael. One of those boys was Stephen O’Neill, Staff Captain of the Third Cork Brigade, Section Commander of the West Cork Brigade Flying Column, but also my great uncle and my dad’s godfather. We realised quite a few things that day, such as how ignorant we were of Irish history. We learned also that these fighting men of Kilmichael were extremely brave, incredibly hardy, ready and willing to make the ultimate sacrifice and are rightly talked about and commemorated to this day. Not only that – we had a war hero in our family (just not the kind that can be celebrated too readily in the UK) and the family could not have been prouder.

I have since devoured all the reading material I could find on West Cork’s vital role in the Irish War of Independence, and Uncle Stephen is mentioned several times. By all accounts, he was dedicated to the cause, was valued by his peers and acquitted himself with valour, but after playing an important role in many engagements and going on the run, was captured and spent a year in British prisons. After the war, he ran a shop in Clonakilty and worked in the building trade, amongst other things, then lived out the latter part of his life in Co. Kerry with his wife and family. He sadly died on July 7, 1966, just days before the unveiling of the Kilmichael monument, an event he had been looking forward to attending.

The remainder of our trip was of course very enjoyable but when Iain and I look back on that week in Ireland; it is our West Cork experiences that we value most. It was almost as magical for him as it was for me.

The magic didn’t stop there however – when I went home and told my Dad all about what had occurred, it inspired him to make a trip over himself and he was able to reconnect with his long-lost family, so that chance encounter on a Spanish island gave rise to a remarkable chain of events and made a lot of people very happy.

In 2003, I made another pilgrimage back to Dunmanway and discovered that, sadly, Denis and Michael had both passed on. The TV shop was closed down and empty, which was a shame, but I was delighted to find Margaret still running the pub. She had changed its name to Nealums in tribute to Denis after his death, as Nealum was the affectionate nickname the locals had for him. It was wonderful to be back, this time with my son Euan, and the reception we received took me right back to those earlier days. I kept in touch with Margaret thereafter, mostly by way of Christmas cards and was greatly saddened to hear of her passing in 2019. Her brother’s family informed me, and invited me to visit them, so I have a new connection with my Irish family.

Before I left that day in 2003, I bought a print of a lovely painting by local artist James McCarthy: ‘Early Morning, Dunmanway’ from 1967, in which a group of men in work clothes are waiting outside Denis O’Neill’s pub. It has held pride of place on my wall all these years and I look at it often, with great fondness.

My wife and I had been planning a trip to visit Margaret for quite a while before we heard the sad news. We decided to go anyway and in January 2020, from old haunts in Donegal, we journeyed in our wee camper van, down the stunning Wild Atlantic Way to West Cork, with some unexpectedly beautiful weather.

The pub had closed down after Margaret’s passing and, as I stood outside the locked door, its emptiness echoed my sense of loss. It had felt to me like the heart of West Cork and the seat of my family. I was still glad to be there, as it felt like I was paying tribute to all those we had lost, including my Dad, who had passed away in 2006. I had his old Dunmanway cycling photos with me and managed, with a bit of detective work, to find the exact spots in which they were taken. I had also brought a photo of the painting I love so much, so I tried to recreate that too, 53 years after it was painted.

West Cork, you may have gathered, is very dear to me and will always be in my heart. The pub and the people I knew may be gone now but my ties to the place still feel strong. We had intended to investigate the area much more thoroughly during our most recent trip, but Ireland is full of the most wonderful distractions, and we were pressed for time, leaving us unable to achieve all that we had planned to see and do. This just means I’ll have to come back very soon – to revisit the farm at Reenroe, and find my great grandparents’ grave, visit Uncle Stephen’s grave and his old shop in Clonakilty and do a lot more detective work and nosing around. Mostly though I’ll return just to be in West Cork, the place of my ancestors and kin, and to feel it soak into my bones. It is part of me now – I suppose it always has been – and I feel lucky to have such deep-seated connections. I also feel hugely privileged to have known the people I met and to have experienced all that I have.

I still wonder what became of that young man from Cork city though – I feel like I owe him a huge debt of gratitude, but he’ll probably never know anything about his accidental, yet vital role in my amazing West Cork family story.

If anyone would like to get in touch with Paul regarding any aspect of this story, he would love to hear from you at pauloneill99@yahoo.co.uk.