The shape of things

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

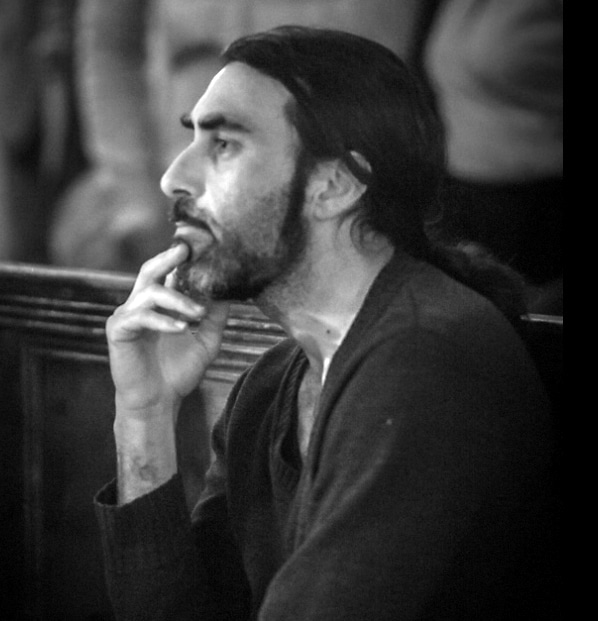

Ian Humphreys is quietly spoken, generous, down to earth and quick to laugh. He is also a painter of imminence, of quiet intensity, a minimalist of immersive colour fields, whose canvases pulse, shine and shudder like the morning sun burning into the coldest sea. ‘My Journey in Paint’, a retrospective of Humphreys’ work, which ran through September at the Kenmare Butter Market, establishes the painter, in no uncertain terms, as a master of the post-expressionist sublime. In this designation he stands alongside Michael McSwiney and Tom Clement, as one of Ireland’s finest exponents.

‘My Journey in Paint’ spanned two decades of work, from 1999 – 2022, incorporating several early still life and figure pieces, off-setting the monumental abstractions which formed the majority of the show. ‘Electrum’ (2022), which hung on a mobile wall in the middle of the gallery, is perhaps the greatest of the latter, and landed directly on the eye upon entry. Its horizontal bands of shimmering silver and gold hover over pale, muted fields of ochre and umber. Staccato strokes of impasto counter blazing horizontal streaks of the brush, the velocity of which blends and quickens bands of colour into interminable, endless horizons.

Humpheys writes, “I try to work as nature rather than from it.” In intention these paintings are non-representational, but they are both filled with, and welcome, association. The myriad qualities of light as it falls upon the sea, from grey to silver to gold, the colours of rocks, seaweed and lichen; all the permutations of atmosphere which envelop his coastal home (now in Rossbrin, and formerly Heir Island) infuse their way into his canvases. This may explain his subtle, largely earthy palette, a significant point of difference to the intense colour range of Sean Scully, whose pictorial strategies might otherwise recall Humphreys’ own.

Far from being formal expositions or purely internal constructs, (such as we might find in Scully’s work) paintings such as ‘Electrum’ and ‘Lundy’ (pictured) are subliminal responses to Humphreys’ environment. We can think of this as non-representation delivering meaningful association. Where early Modernists, such as Piet Mondrian sought to block nature out, painters such as Clement, McSwiney and Humphreys invite it in. We are welcome to see and feel the light of the sea, the shimmer of the horizon, the burnt orange of a dying sun without any of it being represented. It is there and yet it is not and herein lies the magic.

The dance between intention and effect, non-representation and association puts me in mind of the work of the 19th century painter James McNeil Whistler, whose most poetic work was of the Thames in fog and at night, ghostly canvases which he called ‘Nocturnes’, after the music of Chopin.

For Whistler, a painting of the Thames in fog was a pretext for a composition, a window into reference-free, mood-laden abstraction. For Humpheys, more than a century later, an abstract colour field is a window into the sea, the sun, the forest; into the very atmosphere of his world.

In 2014 Humphreys’ world of horizontal motifs (lines of sand, bluff and sea) was upended when he accepted an invitation to take up an artist residency in the Joseph and Anni Albers Foundation in Connecticut, USA. Suddenly surrounded by forests his work began to take on a vertical aspect, generating such work as the monumental ‘Vermillion’ two years later.

Immediately on his return to Ireland Humphreys painted ‘Homage to Joseph in Silver and Grey’ (2014), his most Rothko-esque piece, included in ‘My Journey in Paint’. The Rothko association is one which Humphreys welcomes, some of his favourite work being Rothko’s ‘Seagram Murals’ in the Tate. Other influences for the artist include the colours of Giorgio Morandi and the ceaseless working processes of Alberto Giacometti, the latter mirroring his own eternal “hunt for the image”, as he scrapes, brushes, gouges and glazes his work into being.

There is a wonderful balance between small and large, intimate and epic, ephemeral and physical in Humphreys’ work, which this retrospective revealed to great effect. From a large work in white, for example, one turned to a small watercolour in red ochre, titled ‘Rust and Bach Cello Elegy’ (2014). This, in turn linked to larger oils with musical titles, such as ‘Bach Cello Suite 2’ and ‘Jacqueline’s Elgar’.

Humphreys’ penchant for musical titles (‘preludes’, ‘fugues’, ‘sonatas’) is resonant of a long line of modernists, beginning with Whistler (and including Joseph Albers) who likened painting to the non-representational nature of music. It is a useful language for Humphreys, who finds there is much in common between the two. He explains that paintings, no matter their size or medium are “a collection of marks, an arrangement of ‘notes’ with spaces in between, like pregnant silences in pieces of music”.

The above being said, the ephemeral qualities of watercolour are but a gentle counterpoint to the rugged physicality of oil; a thin wash but an echo of the oily shore of the ‘quickening’ where matter becomes spirit. The oscillation between the two is where ‘My Journey in Paint’ shone as an exhibition; the works by turns receding and swelling, thunderous and silent, the driving force of the brush more resonant of the tide than a pictorial seascape could ever be, but not limited to that either, as Humphreys’ first and foremost concern is the unimpeded act of painting itself, where all else drops away, where the silences are silver.

Ian Humphreys’ work is of an international calibre, an assessment affirmed by his endorsement from the Joseph and Anni Albers Foundation. He is comparable in the post-expressionist field to Clement and McSwiney and rivals Sean Scully in quality if not scale. His timeless paintings are welded to the world he lives in, a window from non-representation into the mist and fog of association, Whistler’s portal rotated and seen through the other side.

For detailed images of the works discussed and for all enquiries please go to: ianhumphreys.ie | email: ianhumphreys4@gmail.com. Ian is represented by Mill Cove Gallery in Ireland and Lime Tree Gallery, Bristol, U.K.