The shape of things

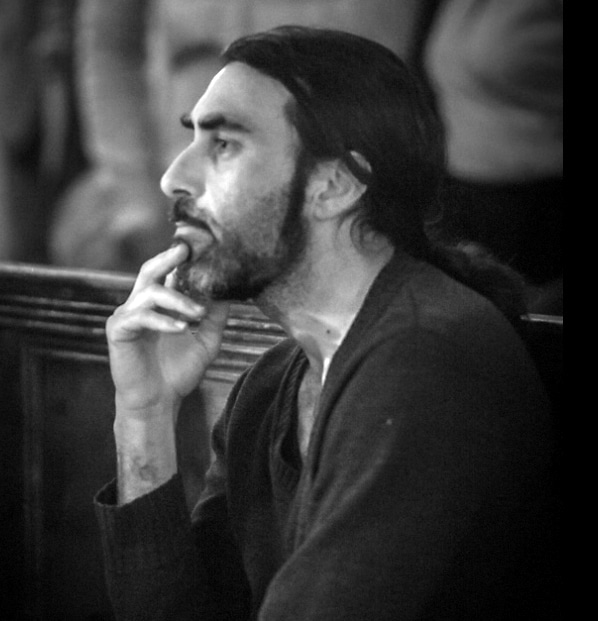

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

More than any other artist in history, the work of Anselm Kiefer conjures the tragic aftermath of war. His trademark canvases, typically heavy with oil, acrylic, tar, straw and lead, breathe the very atmosphere of desolation and ruin. They are monumental, full of surging, yet distilled energy; the human traces, whether they be blackened clothes, old shoes or strands of hair are filled with the utmost poignancy.

For Kiefer it could not have been any other way. The son of a Nazi lieutenant, the young Kiefer set himself the task, from the very beginning of his creative journey, of facing the shame of the Holocaust and the catastrophe of Nazism. Five decades later, and one of the most revered artists in the world, Kiefer’s commitment to a psycho-aesthetic reckoning with Germany’s past remains unabated. So much so that the aesthetic language he has built, even if directed towards another subject, continues to echo all the ashen landscapes he has confronted and plumbed.

His recent collaboration with the city of Venice has proven no exception. Invited to create an installation of paintings for the Doge’s Palace, to mark the 1600th anniversary of the city’s founding, Kiefer has created possibly the most sublime evocations of ruin, spiritual darkness and spiritual light, of his career.

Stepping into the Sala delo Scrutinio, where the Venetian Doge’s were once elected, visitors have been confronted this year with soaring canvases of ashen gold and silvery lead; an installation of paintings measuring up to 15 x 8 metres each, effectively forming a room within a room, an ‘inner skin’ of images, temporarily blocking works by Tintoretto, Palma the Younger, and others on the palatial room walls.

In the exhibition catalogue Gabriella Belli acknowledges that Kiefer’s Venetian cycle does not “arise from the glory of the Serenissima” (the most serene republic), but from the fire in 1577 that engulfed the Sala delo Scrutinio. Whilst this may be so on one level, it is probably truer to say that Kiefer’s alchemical processes and decades-long themes happily converged with destructive episodes in the palace’s history.

Where in the past painters were commissioned to glorify the state through history painting, the engagement between artist and state today is quite different. With respect to an artist of Kiefer’s acknowledged standing and calibre it is especially so. For though he may alter some written references and add some new iconographic elements, in respect to the given context, Kiefer will always follow his personal, alchemical vision. The universality of this vision is what enables him to embrace a context such as the Doge’s Palace in Venice, so wholeheartedly.

It is true to say that the two – artist and city – serve each other, but ultimately the city has received a Kieferian cycle more than a Venetian one. It could not have been otherwise, and happily so, for the contrast and synergy of Kiefer’s work within the Sala delo Scrutinio is positively electrifying.

For all of Kiefer’s material complexity and thematic scope his pictorial strategy, when it comes to painting, is often beguilingly simple: land/sea, horizon, sky. It is a format which has served the artist well, even when dealing with interiors, where floor boards replace furrowed fields or lines of waves. Unsurprisingly it is also the stage upon which he performs his Venetian cycle.

In one enormous piece perspectival lines lead to a distant horizon. The surface, heavily built up with staccato strokes of oil and milky emulsion looks for all the world like a classic Kiefer snow-covered field. Sculptures of submarines, made out of lead, are anchored to the canvas, ‘riding’ the furrows. Kiefer has used the submarine motif for decades, and not always to represent the obvious; in this context it stands for Venetian historical maritime power, and the furrows read as waves.

Suspended across the top half of the dark, charred, gold-shot sky, are five supermarket trolleys, a rusted tricycle, cargo bike and bicycle, laden with straw, coal, clothing and linen. A colour scheme of black, red oxide, naples yellow, ochre and gold harmonises the suspended objects with the painted sky. Lead tags hang from the trolleys, each inscribed with the name of a Venetian Doge, the sole sign connecting the work to Venice. It is a work of incomparable genius, its energy and resonance unmatched by any contemporary. The trolleys and bicycles, as signifiers of Venetian trade, are startlingly incongruous – they hit just the right note. But does the work really connect with Venice? Does it matter?

In terms of scale, colour and energy, the works emanate a sublime grandeur every bit equal to the Doge’s Palace. The history of the palace, in particular the fire of 1577, in which many paintings and books were lost, also gave Kiefer a conceptual inroad for the cycle, connecting with decades of his own work involving books and entire libraries made of lead.

The opening work, in the smaller room before the Sala delo Scrutinio, is a vintage Kiefer snow-covered field of burnt-out stumps. Protruding from the canvas are charred books made of lead, whilst along the horizon line is scrawled the title of the series: “Questi scritti, quando verranno, daranno finalmente un po’ di luce” (These writings, when burned, will finally cast a little light). The quote, from the Venetian philosopher Andrea Emo, in a way sums up Kiefer’s modus operandi.

The scrawled title, in Italian, anchors the entire cycle in its Venetian context, even whilst the stumps of a burnt field, lead submarines and rusted tricycles stubbornly recall Kiefer’s earliest evocations of Germany’s war-ravaged landscape. The combination is energising and points to Venice’s own history of war, from its sacking of Constantinople in1204, to its naval battles with the Republic of Genoa and the Ottoman Empire.

Kiefer’s work ultimately has a life of its own. He offers up to the city of Venice the elements of the earth in all their creative and ruinous fury. If there is any hope of transcendence, it comes with the full weight of the darkness it purports to rise above. Kiefer is not in the business of glorifying a state, but of confronting its dark shadow and transforming it into gold.