The shape of things

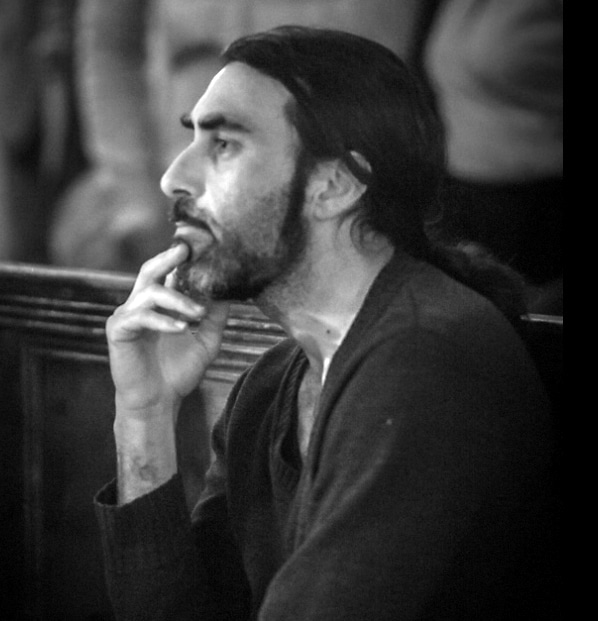

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

I have, throughout this year, mostly resisted writing about art in relation to war, as images of ongoing conflict have never been so widely disseminated, heartrending and explicit, available constantly on everything from social media platforms to highly respected establishment media sites. In 1937, however, when the Spanish Republican government commissioned Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ visual documents of atrocity were not available in 24 hour news feeds; indeed such things did not exist. When ‘Guernica’ was exhibited at the 1937 World Trade Fair in Paris it helped bring world attention to the Spanish civil war; a monumental painting by the world’s most famous artist, in the place of a live video stream.

Writing in the Times and New York Times on 28 April 1937, journalist George Steers published the following eyewitness account of the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica, an account which in its French translation would have a profound influence on Picasso:

“Guernica, the most ancient town of the Basques and the centre of their cultural tradition, was completely destroyed yesterday afternoon by insurgent air raiders. The bombardment of this open town far behind the lines occupied precisely three hours and a quarter, during which a powerful fleet of aeroplanes consisting of three types of German types, Junkers and Heinkel bombers, did not cease unloading on the town bombs weighing from 1,000 lbs. downwards and, it is calculated, more than 3,000 two-pounder aluminium incendiary projectiles. The fighters, meanwhile, plunged low from above the centre of the town to machinegun those of the civilian population who had taken refuge in the fields.”

With the men away at war the victims of the Guernica bombing were defenceless women and children, and it is this fact which Picasso sought to reflect in his aesthetic vision of the horror. As an image it has endured, being one of the most recognisable symbols of the United Nations, which has had a tapestry, commissioned after the original by Nelson Rockefeller, on display in its conference building in New York since 1985 (on loan from the Rockefeller Estate). One might ask why it has remained so cogent when so many other images of war have passed before our eyes? The answers, I would suggest, are manifold, and central to them, Picasso’s singular pictorial language and compositional power.

The pictorial language employed in ‘Guernica’ was the culmination of years of linear deconstruction and shadow play, and was presaged in works such as Picasso’s etching ‘Minotauromachy.’ It was forged as an ‘envelope’ composition, with a central pyramid and sideways pyramids on both ends. Within each pyramid one can discern a centre for the vortex of forms which spiral around it. The forms, shadows, lights and lines spill and intersect, forming tumultuous, jagged planes, which create a sense of frantic claustrophobia, the raw graphic lines, underlined by a chilling and powerful stability.

That ‘Guernica’ was achieved in a linear, cartoonesque language on a scale of over 3×7 meters compounds the overwhelming surreality of the image. A realistic rendering would never have had the same impact, for the pictorial language itself was a dismemberment. Its very delivery was its message, and this, perhaps, is the secret of its longevity.

What ‘Guernica’ has to say to us today is chilling; it echoes Goya’s 19th century ‘Disasters of War’ etchings, Pieter Bruegel’s 16th century painting, ‘The Triumph of Death,’ and so many others in between. It stands for Aleppo, for Mariupol; for Gaza city and Khan Yunis, and for all cities and towns indiscriminately bombed in recent history. Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ haunts every failure of the United Nations’ dream; it screams the failure of nations to live up to its ideal. The seed of this failure is rage. Writing in Rome, in the first century, C.E., Seneca the Younger wrote a treatise on anger, and his words reverberate throughout the centuries:

“…you are right in feeling especial fear of this passion, which is above all others hideous and wild: for the others have some alloy of peace and quiet, but this consists wholly in action and the impulse of grief, raging with an utterly inhuman lust for arms, blood and tortures, careless of itself provided that it hurts another, rushing upon the very point of the sword, and greedy for revenge…”

The only way out of Picasso’s hallucinatory vision is to heed Seneca’s words and quell the fires of one’s own rage; to defend, but not to lash out. That, of course, is much easier said than done, but it is, in a nutshell the challenge of the individual, as much as of the body of nations which comprise our precariously balanced world.