“One house would be attacked and the next spared, there was no telling who would go next and when someone said goodbye to a friend, he said it as if forever. In a few days the town became like a city of the dead. The great county infirmary hospital was turned into a cholera hospital but it was insufficient to meet the requirements. The nurses died one after another and none could be found to fill their places.” – Charlotte Thornley

In 1832, a little girl named Charlotte Thornley, 14, from Sligo, found herself living through an epidemic: A cholera epidemic that claimed the lives of 50 per cent of Sligo’s population. Charlotte and her wealthy, middle class, protestant family however survived. Charlotte grew up and married a man from Derry called Abraham Stoker. The couple had a son called Bram Stoker.

Often mysterious illnesses in the 19th century only affected the working classes: People of means had access to better foods, access to clean drinking water, their houses were cleaner and, most importantly had more modern sanitation. Sickness rates and death rates among the working classes were disproportionately higher than that of the middle and upper classes. However, Cholera held no bias, and had no concern for any socio-economic class structures, which made it all the more terrifying. It killed anyone it came into contact with, within 48 hours, in a horrific and undignified ending. Without medication, a vaccine, and no obvious transmission route of the virus, mass hysteria ensued.

Charlotte wrote about the arrival of cholera in Sligo from the East in her book called ‘Experience of the Cholera in Ireland 1832’:

‘It was said to have come from the East in China, it rose out of the Yellow Sea going inland like a cloud dividing into two, which spread North and South, in those days I dwelt with my parents and brothers in a provincial town in the West of Ireland called Sligo, it was long before the time of railroads or steamboats. But gradually the terror grew on us. Time by time we heard of it nearer and nearer. It was in France, it was in Germany it was in England and with wild affright we began to say it was in Ireland.’

Its reputation preceding it, cholera immediately got to work on its arrival in Sligo in August 1832. The first recorded case was August 11 and the deaths soon were so many and so often that the coffin builders could not meet demand and people were buried in shallow graves, burned, or simply dumped outside the city walls.

One of the first things Charlotte says in her book about its arrival is:

“I vividly remember a poor traveler was taken ill on the roadside some miles from the town and how did those Samaritans tend him? They dug a pit and with long poles, pushed him living, into it and covered him up alive.”

People were buried alive, due to a lack of understanding and a genuine fear of being infected. It was a traumatic time: With no understanding of germ theory and with total reliance on God and folklore as an explanation for essentially everything good and bad in life, panic set in. Full families died overnight. Everyone was dying, with no obvious connection. There are reports of people wandering the streets like zombies, a type of living dead, before succumbing to the virus and dropping dead. These poor souls that took on this side effect of the disease were known as the undead.

Living through a pandemic means we have some context for the panic that this must have brought about. However, in 2022, we understand the science of a virus and how it operates, how it is transmitted, how to mitigate becoming infected; and we have medication, we have vaccines. In 1832, there were none of those things. The best scientific explanation at the time for so many people dying was ‘bad air’ or that odours caused infection. Therefore, people did the best they could to avoid each other. They went into lockdown.

The Thornleys locked themselves into their home for two weeks until Charlotte’s mother went out the back yard one evening and found all their chickens dead. Taking this as a sign from God, the family immediately packed and left Sligo by horse and cart, travelling towards Bundoran in Donegal. On the way they met a violent mob of people led by a local doctor that had become psychotic due to the fear and panic induced by the worry of catching cholera. The mob attacked Charlotte and her family and tried to set them on fire because they assumed, coming from the direction of Sligo, that they were infected. Fortunately, the Thornleys were protected by passing soldiers who took them to the local barracks. However the frightened soldiers there turned them back, but did give them protection on their return journey. The entire trip took a month, as Charlotte noted in her book:

“We returned to Sligo where we found the streets grass grown and 5/8 of the population dead and had great reason to thank God who had spared us through such dangerous and trying times and scenes.”

Cholera killed 1500 people in six weeks.

So where does Dracula come into this story?

As mentioned at the beginning, Charlotte Thornley grew up and married a man called Abraham Stoker. Abraham’s family was from Derry, where in a field near Slaghtaverty is a giant stone under a tree known as ‘The Giant’s Grave’; a tomb where a fifth century High King called Abhartach.

A real person, Abhartach was killed in the 400s. The local folklore around this tomb is that Abhartach had special powers but was universally hated in Derry by the people he presided over. They hired a chieftain from a neighbouring tribe called Cathain to murder him and remove him from power. Cathain murdered Abhartach and buried him standing up.

However legend has it that Abhartach returned from the dead the next day and went back to his kingdom to confront his people. As penance, he made each member of the town give him a bowl of their own blood – which he drank. Cathain, the assassin, is disbelieving, as he knows for sure that he killed Abhartach. So, he goes to a nearby woods to speak to a saint called Eoin, who tells him that Abhartach was never alive, instead he was the living dead. A type of wizard. A ‘Neamh Marbh’, which is Irish for the undead. He is a ‘Dearg Dulai’, which translates as a drinker of human blood and it is impossible to kill him.

Eoin tells Cathain that the only thing that can be done is to put Abhartach in a type of purgatory, a state of suspense between life and death, which can be done by killing him with a sword made from the wood of a Yew tree. Then he must be buried upside down with thorn and ash twigs scattered over his grave. Once this is done, a boulder must be placed directly on top of the grave. Only when these steps are followed and completed will Abhartach be prevented from returning. Cathain follows these directions and, from the thorns that Cathain scattered, grows a huge tree. You can go to Slaghtaverty today and see that tree. Due to that story and the folklore and mystery around it, that tree exists today, undisturbed 1500 years later in rural Derry.

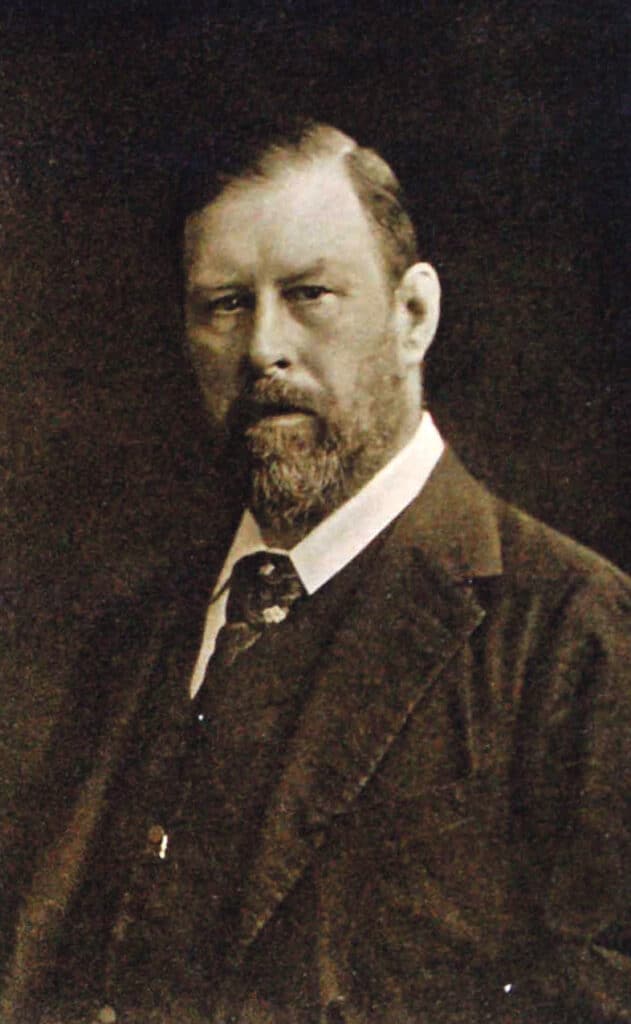

After marrying, Abraham Stoker and Charlotte Thornley had a son, who they called Bram.

Bram Stoker went on to write the book Dracula. A lesser-well-known fact is that Bram Stoker was born with a mystery illness that prevented him from leaving his bed for seven years. Entirely bed bound until he was seven-years-old, the young Bram was undoubtedly in that time told stories from his mother and father’s youth, including the story of Abhartach, who was essentially a vampire. Bram wrote Dracula in 1897 and there are too many similarities to the story above for it to be a coincidence. If you read Dracula and view it through the eyes of what you now know, taking into account Bram’s mother’s experiences, it becomes more than simply a story about an eccentric count who lives in a castle.

Dracula becomes this terrifying unknown wave of death that travelled from the East to the West by ship, infecting people with no clear or obvious method of transmission that causes havoc. Aside from the undead, the coffins, the psychotic doctor and the drinking of blood, possibly the most telling sign of all is that the first person recorded in Sligo to have died from cholera, died on August 11, and Dracula bites his first victim when he arrives in London on August 11. Dracula is a fusion of Bram Stoker’s mother’s experiences during the cholera outbreak in Sligo of 1832 and the story of the undead fifth century High King Abhartach from his father Abraham’s family home town in Derry.

Dracula is Irish!