The daughter of a lighthouse keeper, Mary Ruth Glanville McCarthy spent her childhood in lighthouses on the coast of Ireland, from Donegal down as far as Galley Head in West Cork. The sprightly 90-year-old recalls her journey to the Galley Head and life there with exceptional clarity, as if it were yesterday, to Mary O’Brien, in particular the events of the early hours of March 13, 1945.

Michael, Martha and Mary Ruth Glanville at Innishowen lighthouse.

Mary Ruth Glanville McCarthy today.

Mary Ruth’s father, Sam Glanville, was a seafarer and had volunteered for service in WWI at the age of 19 before becoming a lighthouse keeper like his father before him. Mary Ruth’s memories of her father include much talk of ships, the sea, and far-flung shores, exciting places he had visited on his travels. She enjoyed listening to his stories and recalls how he had a very dry sense of humour. “We saw him as a very wise and capable man.”

Born in 1932, Mary Ruth was one of three children, with an older brother Michael and younger sister Martha.

The only time she ever remembers feeling insecure during her childhood was when her father talked of “joining up” after WWII broke out in 1939. He was stationed at Cobh at the time. Although Ireland had adopted a policy of neutrality during World War II, as a former soldier who had seen action in the First World War, Mary Ruth’s father took a great interest in wartime talk and events, listening to broadcasts on her grandparent’s radio.

“My mother was furious and threatened to leave with us children if he went to war,” recalls Mary Ruth. “There was no further talk of enlisting.”

From Cobh, the family moved to Skerries, Co Dublin before a final posting to Galley Head Lighthouse in West Cork in 1942. Mary Ruth remembers her mother being disappointed with the posting. “She saw the location as being very isolated, particularly for Michael’s secondary school education,” explains Mary Ruth. Sam Glanville had spent time at the Galley Head as a young boy, as his father had been stationed there. “My father was philosophical. He sang the ballad ‘Skibbereen’: A sad song about the effects of the Great Famine…” she recalls.

“As children our biggest concern was our cat Scamp.” It was decided that Scamp would travel in a hamper with the family.

“The journey from Skerries to the Galley Head felt very long,” recalls Mary Ruth.

“It took us all day to travel down from Dublin to Cork, as with fuel rationing, the trains were running on reduced speeds. Scamp had to travel in the baggage van, which we weren’t very happy about! Although it was long, it was quite an enjoyable and exciting journey for us children, with our heads stuck out the window. After many stops, we finally arrived in Cork City, where we had to walk from Glanmire station to Albert Quay Railway station to set out on the next part of our journey to Clonakilty.”

Mary Ruth says she has never experienced such darkness as the walk down Barrack Hill from Clonakilty station to the Imperial Hotel in the town. “There were no lights anywhere and the town was so quiet,” she recalls.

The following morning, December 18, after shopping in Clonakilty for some essentials, the children staring dumbstruck at the women in the West Cork hooded cloak, the family set out on the final leg of their journey for the Galley Head in a pony and trap driven by a local man called Jer.

“I don’t remember noticing the dwellings when we arrived at the top of the road, just the lighthouse tower,” recalls Mary Ruth. “How lonesome it seemed.”

A week later, the family celebrated their first Christmas at Galley Head.

“I don’t know how my parents managed to get the shopping done for Christmas that year,” says Mary Ruth. “My father’s bicycle was our only transport and you’d only get to town once or twice a month in the local farmer’s horse and cart. In those days, Clonakilty felt as far away as America!”

“Somehow my parents pulled it off…there was chicken on the table for Christmas that year and Santa brought little black patent shoulder bags for me and my sister.”

The Galley Head had a telephone line, possibly because of its monitoring role in wartime. However, it was a few years before rural electrification and there was only cold running water in the house.

Mary Ruth recalls helping to polish the brass in the lighthouse and how if you didn’t wind up the ‘weights’, the light would go out.

She and her siblings attended the local national school, a long four mile walk from their home along a rough road. “The school children had a great grasp of the Irish language, much more so than us, and I remember that everyone had lots of cousins nearby,” recalls Mary Ruth, “which of course made us feel even more like blow-in’s.”

Entertainment would have been provided by the ‘play crowd’ who pitched a tent at Fisher’s Cross occasionally. “They were what we call ‘fit-up’s’ today,” explains Mary Ruth, who recalls one group called ‘The Merry Scamps’. Aside from that, there were concerts in Ardfield Hall or a rare visit from a circus.

Possibly the most exciting event to ever take place at the Galley Head however, and one that Mary Ruth still remembers vividly, happened on the night of March 13, 1945.

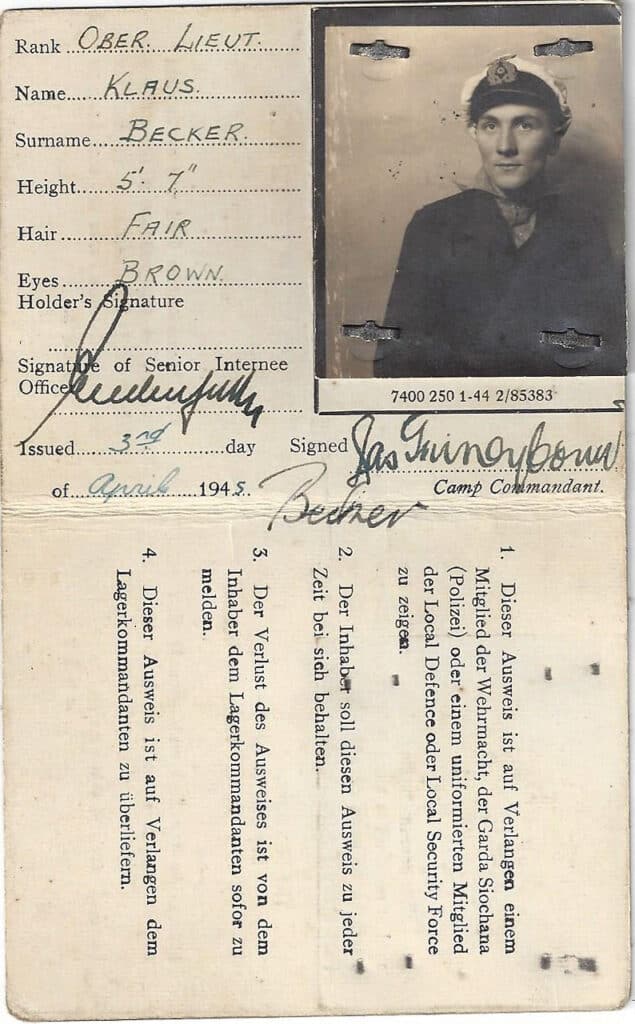

Mary Ruth’s recollection of the night has been published in a booklet by her daughter Mary Rose McCarthy, who has researched and chronicled the events surrounding the rescue of German submariners at the Galley Head. She has also made contact with the son of Oberleutnant Klaus Becker, one of the German submariners. Mary Rose’s hope is to see the Coast Watchers eventually receive the deserved recognition for their work on that night and service during WWII.

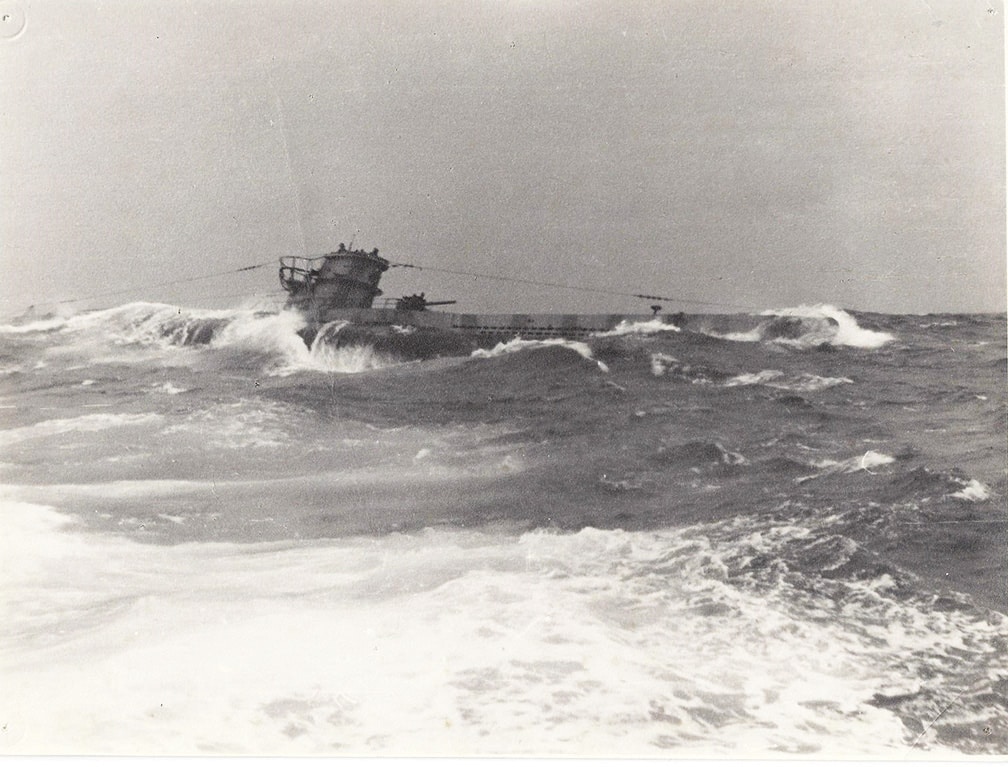

As detailed by Mary Rose in the booklet, the Irish Coast Watchers guarded the coast of Ireland in 82 look out posts in often brutal conditions for the duration of WWII. Conscripted young German sailors lived in ‘iron coffins’, as the submarines were called, also in grim conditions. By their actions, in the early hours of March 13, 1945, the men at Look Out Post 27 Galley Head saved the lives of 48 German submariners from the scuttled submarine U 260.

Klaus Becker’s Irish identiy card when interned at the Curragh

U260 coming into port after a mission.

U260

This is Mary Ruth’s memory of the night, which is published in the booklet ‘Safely to Shore’:

“My father opened the door of the bedroom where Martha and I slept and, as if it were an everyday occurrence, said: “There are German soldiers in Joe’s house. Do you want to see them?

“This statement was beyond our understanding. Why were they in Joe’s house? Why were they in Ireland? Germany, we understood, was at war with other countries somewhere in the world but not in Ireland. Bewildered, we got out of bed and went with Michael and my mother into Joe’s kitchen.

“The assistant keeper at Galley Head, Joe O’Byrne lived beside us with his wife and baby daughter. A third building called ‘The Spare House’ was alongside Joe’s. A telephone was located there.

“On the night of March 13, 1945, all of us, except my father, went to bed.

“He said, ‘I will stay here in the kitchen for a short while’.

“This puzzled me. He was not on duty. Joe had lit the lantern at sunset and he would keep watch until sunrise. The man on duty stayed in a room in the tower, or in his kitchen where the range was always lighting.

“Sometime after we went to sleep, a loud explosion woke us and our bedroom was flooded with a pink light. We were alarmed for a while but quietness ensued and we went back to sleep.

“Our second disturbance was my father telling us about the soldiers. Of course, we wanted to see them. We rushed to Joe’s kitchen where we saw my father and Joe with five or six young men in uniform. The strangers were talking cheerfully together and did not have guns. From his experiences during WWI, my father had a smattering of French and German which enabled rudimentary conversation to take place.

“Soon afterward a Coast Watcher came with more uniformed men making a total of eleven. All were happy to see each other. Joe’s baby was brought in to be admired by the soldiers. One was their Captain, according to my mother, and had children in his home country. They had scuttled their U Boat – submarine – and made their way to the cliffs in a rubber dinghy.

“‘Which cliff?’ I wanted to know, since being an agile climber, I had explored many of them.

“My father said he did not know but I suspect he did. How did they manage to get safely up the cliffs? Their uniforms, as far as I could tell, were not wet with sea water.

“We children took a great interest in the discussion as to what food to give them. Tea was rationed and very precious. It was decided to give them coffee because as was said they ‘were from the continent’ and were accustomed to that and not to tea. Ground coffee was not available. Irel coffee was made with boiling water added to the sweet syrupy essence. What food they were given I cannot remember. The ‘Cork Examiner’ with EIRE printed on it was shown to them and they were delighted. The men knew Ireland was neutral.

“All the while, my mother and the three of us were observing and enjoying the excitement. Either my father, or Joe, or a Coast Watcher, telephoned an authority somewhere to inform them of the situation. There were procedures to be followed in an event like this at the Galley and there had been similar instances in other parts of Ireland.“At sunrise, a member of either the LDF (Local Defence Force) or LSF (Local Security Force) from Clonakilty, with perhaps a Garda Siochana, arrived in a small lorry. Mick Murphy, the driver said to my mother ‘I was just rising the cup to my lips when the call came’.

“They had come to take these sailors, or soldiers, to the Curragh Camp, where they would be interned until the war was over.

“They were happy as they left Joe’s house. They gave us cigarette-tobacco, much appreciated by my father, strange-tasting white chocolate, and pemmican – dried powdered beef – which also tasted strange.

“This I will always remember: as they were walking towards the lorry, a soldier noticed a young woman who had come from the village with the local men to see what ‘was happening on the headland’. He gave a flirty, skipping dance towards her and went away in the lorry.

“I never knew any of their names…”

On that night the Coast Watchers alerted the Courtmacsherry Lifeboat, which subsequently picked up the remaining 37 crew off the coast of Glandore.

Two months later the war in Europe ended and all 48 men returned to Germany.

The wreck of the U Boat is still at the bottom of the sea off Glandore

Following her father’s retirement, the Glanville family moved to Clonakilty. Mary Ruth travelled to England to take up a teaching post and went on to train as a nurse in Birmingham before returning home to Ireland where she continued working as a nurse in Cork. She married her husband Jerry in 1961 and the couple raised six daughters and two sons together. Mary Ruth returned to nursing for a few years when her youngest reached the age of 10, a time she now recalls with some hilarity.

“I’d been out of nursing for so long, I didn’t have much of a clue about anything,” she says. “Penicillin had been renamed all sorts of things and patients were knocking on the door every night looking for valium, which I wasn’t allowed give out. The electric fires in the nursing home were an accident waiting to happen. Twas madness!

“There’s another book in that really!” she says with a twinkle in her eye.

The Coast Watchers of LOP 27 Galley Head (as listed in the Bureau of Military Archives):

Corporal O’Sullivan J.

Volunteer O’Mahony, James.

Volunteer O’Donovan, John.

Volunteer Connolly, Jerome.

Volunteer O’Mahony, J.P.

Volunteer Keohane, Patrick.

Volunteer O’Regan, J.

Volunteer O’Sullivan, James.

Pte Daniel Deasy.

J. Mullins.

Pte Patrick O’Leary.

Pte John Twohig.

E. Sweeny.