The word ‘economics’ makes many people’s eyes glaze over. It all sounds so…abstract: Aggregate demand, Keynesianism, negative deflationary spiral, fractionally higher highs, liquidity preferences But what does all that have to do with real life? Everything of course explains Moze Jacobs.

It’s the language of industry leaders, investors, finance ministers, central and other bankers who have a huge effect on jobs, prices and health, not to mention the environment that we inhabit. Apart from words, they also make extensive use of visuals. Charts. Graphs. Prices going up and down. Supply and demand.

This creates a seemingly safe world, which is completely illusory…and all about maths. Prices are said to be ‘in an equilibrium’ when ‘supply and demand are balanced’. Wikipedia texts wax lyrical about a ‘perfect market’ under the heading ‘perfect competition’. Looking at those pages, you’d say we live in a perfect world with (eternal) economic growth as the greatest good. Except we don’t.

The economy is like a wilfully blind and amoral many-headed monster that has the world in a stranglehold.

It turns a blind eye to greed.

It ignores the need for (and needs of) a healthy community

It is in total denial when it comes to the state of the ‘mother of all resources’: nature.

Nature is an externality to the so-called science of economics. It doesn’t count. Its destruction isn’t factored in. It’s visible all over the world (just think splintered rainforest, dead orangutans, polar bears in a sea of trash). But it’s nowhere to be seen in those economic graphs.

That’s why we (as the West Cork Doughnut Economy Network) like the doughnut diagram, created by Professor Kate Raworth, who calls herself “a renegade economist focused on making economics fit for 21st century realities”. Just like that eternal growth fantasy curve, the picture tells us what an economy should (and hopefully could) be like. No longer a money-generating machine for the (happy?) few but a circular sweet spot for the many in wholesome green.

But how do we get there? Raworth shows us, in hazardous red, the deficiencies that are glaringly obvious under the current economic system. On the outside it shows the dangers of living beyond nature’s means. The gaping hole in the middle signifies areas of individual deprivation. In Raworth’s words, “Many millions of people still lack life’s essentials, living daily with hunger, illiteracy, insecurity and voicelessness.” She wrote that in 2017 when business as usual was expected to continue for the foreseeable future. Our ‘now’ looks very different.

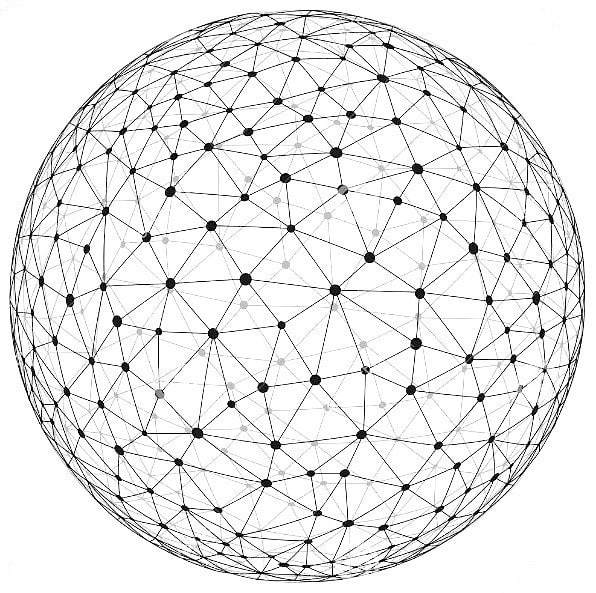

What to do? Does anyone have a clue what a vital and ‘better’ economy would look like? Thankfully, Kate Raworth does. She has provided us with another graph that might help repair the hole in the middle and the devastation at the edges: A network of flows.

“Imagery is incredibly powerful,” she states. So let’s imagine a thriving economy consisting of numerous (and mutually connected) local economic and community hubs. Food grown locally (and chemical-free), local employment opportunities identified (what services would local people value?), waste recycled and reused (so it becomes a resource). Money and thought poured into making people healthier (physically as well as mentally). Local and regional conversations about what people want and need, including for their environment…

Perhaps not purely coincidentally, the government has just started up a Climate Conversation online that invites people to share their views on the upcoming Climate Action Plan that is meant to mitigate the climate crisis. The website also sports a jargon buster.

Sounds good. Let’s hope it will translate into real and meaningful action.

The crunch is not what well-meaning, socially-inclined, heart-centred people think should happen. The crunch is whether governments all over the world will be prepared (and able) to make big business and dictatorships walk the walk.

The West Cork Doughnut Economy Network welcomes your views. Contact: westcorkdoughnuteconomynetwork@gmail.com.