The shape of things

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

War has always had a way of challenging the relevance of the arts. The response of many artists following WWI was to create ‘dada’, or ‘anti-art’ and nonsense theatre. What was the point of art, after all, when it failed to civilise and quell the hidden beast of war? Following WWII the German philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote, in a sentiment which, for him, encapsulated the guilt of survival: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” (Cultural Criticism and Society, 1949). The innumerable works of poetry, prose, art and film which have attempted, since, to process the barbarity of the Holocaust prove Adorno, at least partially, wrong: as much as it may have felt “barbaric”, it was necessary (Adorno later qualified his earlier statement to say as much); the poetry of Paul Celan, the art of Anselm Kiefer, the testimony of Primo Levi and the films of Andrei Tarkovsky were all fundamental to the foundations of post-war European culture, precisely because they attempted to process personal and collective trauma.

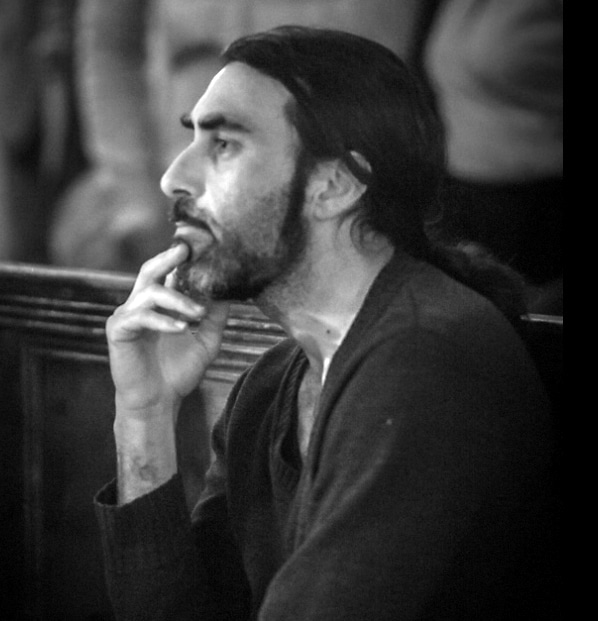

For Dublin-based artist Alan Mongey the attack on the World Trade Centre in 2001 and the ensuing military response by the West precipitated a decades-long creative investigation into the dialectics of state sponsored propaganda, coercion and violence. It has lead, most recently, to the creation of a body of work titled ‘Codes of Conduct’, created largely in Dubai (where the artist lived for seven years) and to be shown in Gallery Asna, Clonakilty Arts Centre, through September. As war once again destabilises Europe and nuclear tensions rise ‘Codes of Conduct’ strikes a prescient note. It is an example of how an artist, rooted in conceptualism, can generate meaningful and urgent social discourse.

By turns clever and inventive, serious and playful, thoughtful and witty, Mongey’s work leads the viewer, via the artefacts of childhood and pop culture into a contemplation of the dark underbelly of state-sponsored violence and surveillance. The work comes in a variety of forms: sculptural assemblage, manipulated, found, and bronze-cast objects, paintings, stencils and installations. According to Mongey “the subject matter dictates the medium.” He is lead by his subject, in conceptualist fashion, but is deeply invested in the object in what is essentially a postmodern approach.

Mongey’s creative strategies reveal a powerful dialectic between language and content: for example, a sculpture of a soldier, titled ‘Band of Others’ is made up of 8000 toy figurines; objects of play are joined to form a meta-object, representing, perhaps, a person’s journey from childhood to military service. This surprising dichotomy of means and meaning is resonant of Picasso’s epic composition, ‘Guernica’, where the innocence of a child-like line contrasts with the horror of what it depicts. The innocence of the one sharpens the violence of the other; we are cut to the quick as we sense – perhaps unconsciously – that childhood itself has been forever stained, forever lost.

Like ‘Band of Others’ Mongey’s ‘Walk the Line’ (2018) utilises figurines. This piece, however, is cast in bronze and plated in gold: 13 miniature bronze figures walk in line, along the top of the barrel of a gold-plated bronze pistol. A 14th figure walks vertically down, over the opening of the barrel. It’s toy-like nature, like in ‘Band of Others’ underscores its resonant critique of the soldier’s duty to “follow orders”. By casting and plating ‘Walk the Line’ in precious metals Mongey wryly critiques the values of the state; ‘here is your culture’, he appears to say: obedient soldiers walking down the barrel of a gun.

The ‘ready-mades’ of Duchamp, Hirst and Koons are clearly important exemplars for Mongey; we feel their echo in his cast-bronze pistols and the melted toy plastic weapons that comprise his ‘Shadow Play’ series. Crucially, however, Mongey transforms his material; they are never left as simple ‘ready-mades’; they are not the stuff of Dada or the hollow gestures of conceptual self-negation. They creep, rather, into the world of the postmodern, alarm bells ringing.

Mongey’s two dimensional work riffs off pop art and street stencils, the hard edge chromatics of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol never far away. His paintings include advertising images for boxes of toy soldiers, black and white paintings of surveillance images and sprayed stencils in want of walls. There is is a raw, modernist grit to Mongey’s surveillance paintings, and whilst they lack the finesse and finish applied to the sculptural work, they give ‘Codes of Conduct’ an expressive edge it would not otherwise have. One cannot help wondering, however, if that ‘expressive edge’ hits the right note? A photo-realist rendering would perhaps be more forensic, colder and closer to its subject.

These minor criticisms not withstanding, Mongey is clearly a serious artist with something to say and the means to say it with. He has a great gift for assemblage and a sharp eye for meaningful juxtaposition. It is prescient work which answers the call of relevance and invites us to engage.

‘Codes of Conduct’ opens on 3 September, 5:30pm, at Gallery Asna, Clonakilty Arts Centre, Asna Square, and runs until 24 September.