The shape of things

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

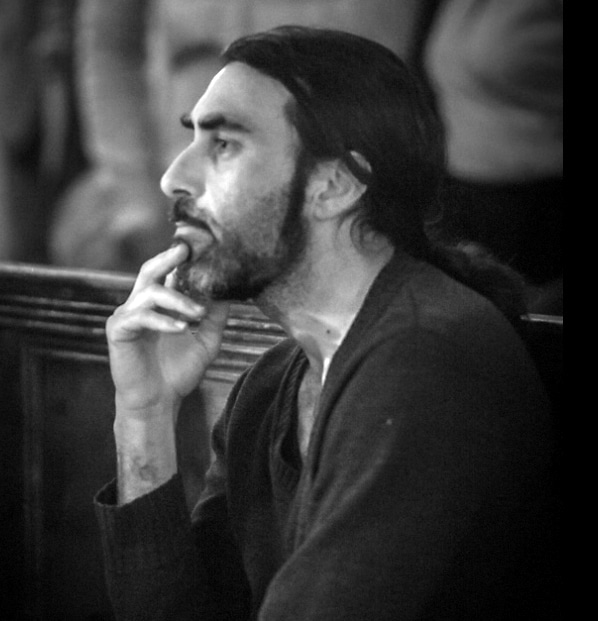

Much has been written over the years about the surprising, witty, icon-flipping paintings and sculptures of Australian artist John Kelly. His monumental bronze, ‘Cow Up A Tree,’ is instantly recognisable, and has graced the boulevards of many cities throughout the world, from Melbourne to the Hague, ever since its first outing in Paris on the Champs-Elysées, in 1999. In West Cork it has its permanent home on Kelly’s coastal property in South Reen, where it incongruously, and majestically overlooks the Celtic sea.

Over the decades Kelly has engaged with, repurposed and transformed iconic elements of Australian identity and art history, whilst in the process, embroidering his own work into its fabric. His work is laconic, inquisitive, and disarming, as he is himself. He plays on identity, calling himself “an awkward bugger” (you can’t get more Australian), rattles the chain of arts council bodies, and cleverly turns their own motifs into art (Kelly used the Australia Council logo, for example, as the basis for his iconic series of kangaroo paintings and sculptures).

So what is this “awkward bugger” all about? As a fellow Australian artist I recognise some of his references and am surprised by others. His ‘Dobell Cow’ imagery, of which ‘Cow Up A Tree’ is one example, has its origins in the war camouflage work of Australian painter William Dobell (1899-1970).

During WWII Dobell was enlisted, alongside other artists, to create life-sized papier-mâché cows for the Australian army, in a rather strange attempt to convince marauding Japanese pilots (who never actually materialised) that the army bases, factories and airfields below were, in fact, farms. This story, which Kelly came across in his reading, was to become the catalyst for three decades (and counting) of artworks dealing with the concept of art as camouflage, art as hoax. From the early 1990s Kelly’s ‘Dobell Cow’ paintings, which imagined a herd of papier-mâché bovines in various configurations – began to make Kelly’s name, both in Australia and in the U.K.

The configurations have been many and varied and speak to Kelly’s fascination with painting and sculpture as a playful repository of cultural histories and symbols. Painted with a Magritte-like surreality and stillness, Kelly’s faux-cows have been stacked, dispersed, dissembled and reassembled. They have been joined and supplanted variously by depictions of the Australian horse-icon ‘Pharlap,’ George Stubbs’ painting of a zebra from 1762, figures of men attempting to lift, enter, reposition and paint them, and Japanese war planes crashing around them.

Kelly’s ‘Dobell Cow’ has, over the years, become a language unto itself which he has used to generate everything from personal metaphor, such as in ‘Man Lifting Cow,’ a tribute to his father, to cultural symbol, such as in ‘Cow Up A Tree.’ The latter keys into a history of floods in Australia where both debris and livestock have often been stranded on high. ‘Cow Up A Tree’ also invokes Sidney Nolan’s 1955 painting, ‘Ram Caught in Flood,’ suggesting a direct association between Nolan’s work and Kelly’s.

It is telling to see online, images of Kelly’s works displayed alongside those of Sidney Nolan in a Sotheby’s Australia auction. Though decades and generations apart they go well together, for it is Nolan’s generation of mid-twentieth century modernist painters that Kelly’s work speaks most to. The strategies of Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd were also driven by a desire to grasp and make poetic symbols of national identity. It was Nolan, more than any other, who gave the outlaw Ned Kelly, a space in Australia’s cultural history, who embedded him as an icon in the national psyche. His series of simplified Kelly figures, in slitted, black-square helmets, against ochre desert and cobalt sky, is the very essence of mid twentieth century Australian art. It is an aesthetic and sensibility which sits squarely with Kelly’s own.

John Kelly, whose father was Irish, his wife Christina (British and also an artist), and son Oscar, live on a beautiful property in South Reen, West Cork. Theirs is a story of counter-migration, and Kelly has not been indifferent to the environs of their adopted home. A surprising side to his work eschews the power and irony of symbolic motifs related to Australia, and embraces the romantic idyl of en plain air painting in Ireland. It is perhaps true to say that different lands and histories require different creative approaches. Representing the Australian landscape is complicated; it is bound up in a history of Anglo-colonial representations on the one hand and Aboriginal Dreamtime images on the other. In the twentieth century the Neo-Romantic, colonial approach shifted to a radical modernist one. The bleak, distilled, mood-filled paintings of Russell Drysdale (1912-1981), the spare minimalist, yet haunting canvases of Fred Williams (1927-1982), and the character-filled, paint-streaked backgrounds of Nolan and Boyd gave Anglo-Australia a fresh perspective on what was seen as an often hostile landscape. By contrast, depicting the Irish landscape, for an Anglo-immigrant at least, is a relatively straight-forward affair, uncomplicated as it is by radically different modes of Indigenous expression. One could say that the European mode fits the European landscape.

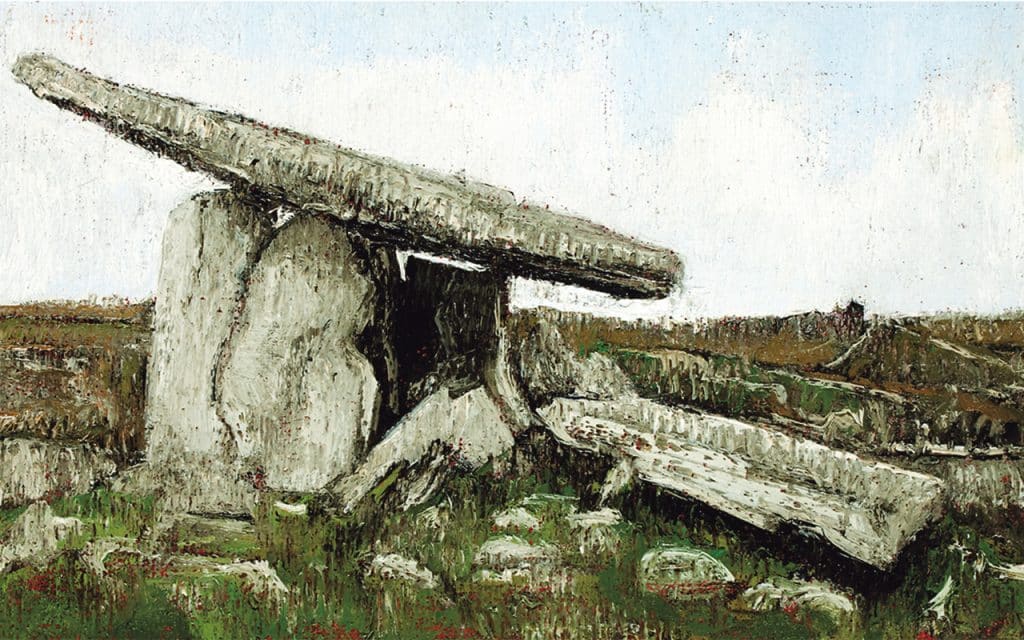

John Kelly inherited many of his Australian forebears’ modernist traits and brought their distinctive style with him to the U.K and Ireland. As early as 1995 John Russell Taylor, writing for Galleries U.K. astutely noted a Fred Williams-like quality in Kelly’s backgrounds. Looking at his visceral and supple paintings of Castlehaven and the Burren from 2013-14, I am struck by a combination of Williams’ line, John Perceval’s painterly quiver and Drysdale’s mood-filled stillness. It is as if the Australian outback was haunting the Burren.

The difference between Kelly’s renderings of Australian airfields and pastures and his en plain air work in Ireland is that he is here painting the landscape directly, for its own sake; freed from the complex politics of representation, which challenges every painter in Australia, Kelly has tuned into his Irish environment, painting dolmens, ruins and bays with a modernist sincerity that contrasts markedly to his post-modern practice of symbol-juggling and myth-making. His Australian landscapes are stages for symbols, his Irish landscapes are songs of presence.

The myth-maker, the creator of ‘Dobell’s Cows’ and the more recent ‘Dummy Horse’ is a Magritte-like figure whose bi-line could easily be ‘This is not a cow.’ The sincere en plain air painter, engaging in the open with his wild Irish environs is, by contrast, a Fred Williams-like figure immersed in the poetry of landscape. John Kelly’s life and work thus represents a counter-migration of aesthetic modalities, which follows his own fascinating journey between cultures.

John and his wife Christina Todesco Kelly, will be holding a joint exhibition at Cnoc Buí, Union Hall, from August 22 – September 8. To view more of Kelly’s work visit:

www.johnkellyartist.com