“Time me gentlemen.”– Robert Liston

If you needed surgery in the 19th century, the pace at which it could be performed was paramount to the patient. The reason being that anaesthetic, antibiotics and antiseptics had all not yet been invented. Therefore, if you needed an operation such as amputation, mastectomy, lithotomy and so on, the speed at which the operation could be performed was the single greatest prerequisite. Quick surgeons were the most popular, as this meant the patient was under the knife without anaesthetic for the least amount of time possible.

Obviously, mortality rates were appalling and even if the patient made it through the initial procedure, they usually died from complications post-surgery. Gangrene, infection and sepsis were all common, as not only was there no anaesthetic for the surgeries, there was also no education or knowledge of germ theory. The same knives, saws and blades that were used on one patient would be used on the next patient, without disinfectant, as this had also not been invented yet. It was also common for surgeons, when swapping surgical tools, to hold the bloody ones in their mouths. Infections were rampant and hospitals were disgusting. So much so that the hospital bug catcher (who would try rid the hospital of visible insects and maggots) was paid considerably more than the surgeon.

In the Victorian era, hospitals were for the poor. If you were very wealthy, or middle class, and needed an operation, you paid extra for the surgeon to perform that specific operation in your home. There are records of women receiving mastectomies and people having limbs amputated in their kitchens and dining rooms. As strange as this sounds it was considerably more hygienic than having your operation performed in the hospital.

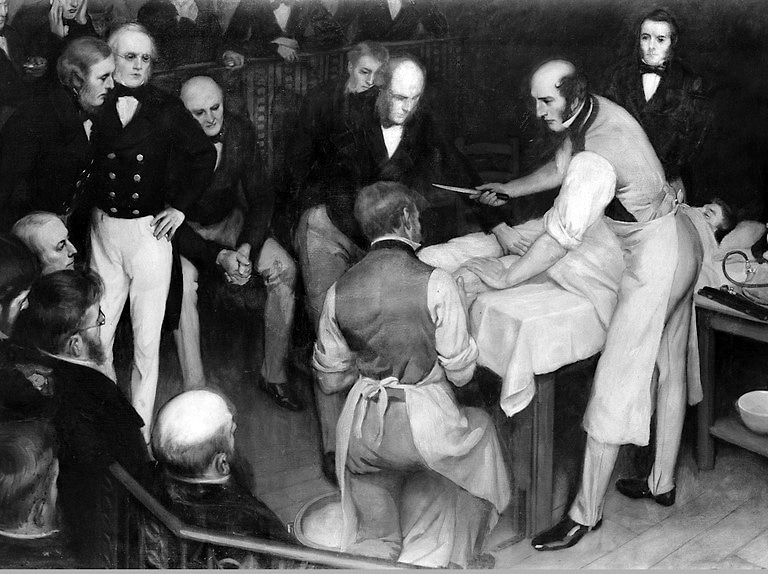

In a previous article I spoke about ‘The Fastest Knife in the West End’ – Robert Liston. He was able to perform an amputation in 30 seconds. Other surgeons could take as long as 90 minutes. Robert Liston became so popular than he began to charge an entry fee to his operations and would fill the room with spectators. It is also recorded that he had queues of potential patients outside his operation theatre waiting to see him; many would wait in line for days and weeks. This was preferential to getting seen by an inept surgeon immediately but being under the knife for an hour or longer without anaesthetic. Makes sense. When he would walk into the operating theatre Liston would shout “Time me gentlemen…!” and the audience would time the operation on their pocket watches as a sport. The audience would sit and watch while he performed amputations on a conveyor belt of patients for hours.

It wasn’t until 1876 that a British surgeon named Joseph Lister went to the United States and spoke about germs playing a part in people dying post-surgery, that hygiene during surgery and post-surgery became a common topic. Lister was the first person to realise that there was an invisible element affecting the wounds of people and he proposed this idea to one of his audiences. A spectator, chemist Joseph Laurence, was fascinated and went on to invent antiseptic in 1879. He named his product ‘Listerine’ after Joseph Lister. This product changed the course of surgery – surgical equipment began to be disinfected and wounds were treated better. The mortality rate of Victorian surgery plummeted.

But prior to 1879 there was none of the above; the fastest surgeons were still the celebrities and the fastest, sharpest tools became incredibly expensive and in demand. This is how the Victorian Amputation Saw came to prominence…and quickly became a huge failure.

The Victorian Amputation Saw, or The Clockwork Saw as it is sometimes known, was invented in the 19th century by a man named WHB Winchester, a surgeon who was fixated on reducing his surgery time. Winchester wanted to make an instrument that would speed up the process of taking off a human leg. Once the circular saw was wound up to the maximum it was released and the blade would spin. The idea was that this would make the operation faster but it was a complete disaster.

The main pitfall of the Clockwork saw was that what Winchester gained in speed, he lost in precision. It was an extremely difficult tool to manoeuvre after the crank was wound up and let go. The first and only time it was used by Winchester, he accidentally took off his assistant’s fingers. It was such a failure that it never made it out of prototype phase. The only Clockwork Saw in existence is on display at the Huntarian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

It wasn’t just Winchester who was unlucky in his exploits, and it wasn’t all glory for Joseph Liston, who had his fair share of failures as well. Once, during an operation, he removed a man’s testicle whilst attempting to remove his leg. In a separate surgery, Liston accidentally sliced off one of his assistant’s fingers and, while changing instruments during the same operation, he slashed the jacket of a spectator that got too close to the procedure. As a result, the patient died of post-operative infection, the assistant died of gangrene from the severed finger and the spectator died of a heart attack from the shock of his jacket being cut. It is the only surgical case in history that has a 300 per cent mortality rate.