Our ancestors believed that there is only a very thin veil between this world of mortals and the Otherworld. This veil disappears completely twice a year, at ‘Bealtaine’ (May Eve and May Day) and ‘Samhain’ (November 1). On these pivotal dates the spirits of the Otherworld intermingled with mortals. Supernatural beings were more than usually active about May Day and the appearance of a travelling band of fairies, of a mermaid, a ‘púca’ or a headless coach was to be expected at this time.

The Great Earl of Desmond, ‘Gearóid Mac Gearailt’ (Gearóid Fitzgerald), a notable wizard in his day, is believed to be seen on May morning in full armour rising from the waters of Loch Gur in Co. Limerick, to gallop his silver-shod horse about the lake. O’Donoghue of the Reeks – in similar array – rides over the Lakes of Killarney. The Fastnet Rock, off the coast of South West Cork, is said to lose its bonds and travel northwards Dursey Island during May Eve and return again before dawn.

With so many spirits abroad, precautions for one’s safety must be taken. Best of all was to remain in the security of one’s own house, but if one had to travel there were ways of protecting oneself. A piece of iron in the pocket gave some protection; a black-handled knife was the best form of iron. Other useful safeguards were a spent cinder from the hearth or a sprig of a rowan tree. If a rowan twig was twisted into a ring and held to the eye it would enable its user to see the fairies clearly.

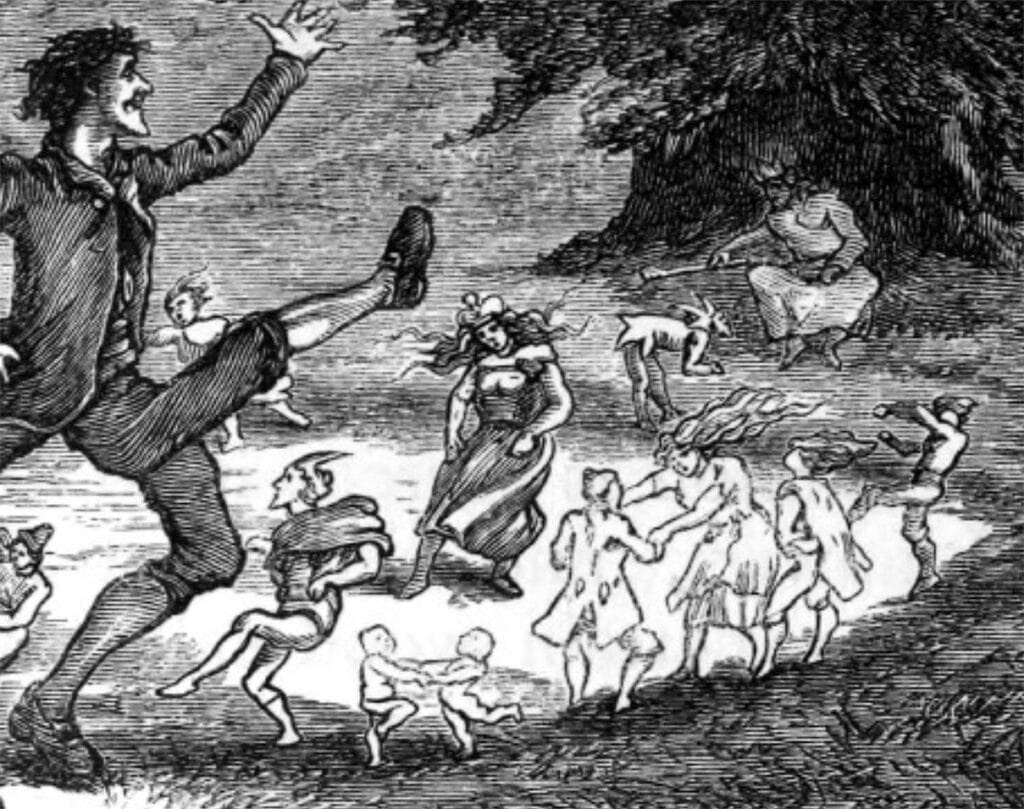

Persons passing near ‘fairy-forts’ (ringforts), lone whitethorn bushes, or other homes of the ‘good-people’, might meet them venturing out to engage in dancing, hurling and other revels or to travel away to visit or to play a hurling match with another fairy group. There are many tales in folklore of encounters between fairies and mortals. In some stories the humans are whisked away to play a hurling match or to entertain at a party, the humans always being returned before morning.

Seán Ó hAo, (1861-1946), a fisherman from Cregg, near Glandore in West Cork, was a fluent Irish speaker. His stories were recorded in 1940 and published in book form in 1985 as ‘Seanchas ó Chairbre’. In one story he tells of a farmer who put his cattle into a field to graze late one May Eve. He was very tired and leaned on a gate to rest. He fell asleep, and waking some time during the night, he saw two teams playing a hurling match in the field. There was great noise and excitement. The whole field was crowded with spirits, all urging on their own team. He returned home as quickly as possible, went to bed and didn’t wake until late the following day.

A favourite pastime of the fairies was to cause mortals to lose their way by bringing down mist or by confusing landmarks. To turn one’s coat inside out was held to be a useful counter to this, as it disguised the person and so confused the fairies themselves, thus enabling the intended victim to escape.

There was a widely-held belief that this was the time of the year when abduction by the fairies was most feared. Infants of both sexes and marriageable young women were most in danger of being spirited away. Usually to confuse matters the abduction left a ‘changeling’ behind, which although at first was just like the person stolen, always changed and often pined away and died, leaving the real mortal in the power of the fairies forever.

The people of the ‘sí’, as the ‘good people’ or fairy folk were known, were said to change their residence at this time and woe betide the unwary traveller or young bride who might be swept away by the ‘sí gaoithe’ (fairy wind). Spells were cast; witches assumed the shape of hares and milk and butter were vulnerable. Stories are told all over Ireland of a hare seen milking the cows on May morning. When pursued by a hound or brought down by a gun the hare turns into an old woman with blood flowing from the wound.

It was customary in places to drive the cattle between two fires to safeguard them against evil. In Irish they said ‘idir dhá thine Bealtaine (between the two fires of May); this has come also to suggest that somebody can’t make up their mind. Holy water or blessed ash was sprinkled on cows and also on boundary fences or tillage fields as a safeguard. In ‘The Farm by Lough Gur’, by Mary Carbery, we have a colourful description of how the maids counteracted spells. ‘They strewed primroses on the threshold of the front and back doors – no fairy can get over this defence – and in cow byres they hung branches of rowan, while the head dairy woman sprinkled holy water in mangers and stalls. The milkmaids at the end of an evening’s milking stood to make the sign of the cross from froth from the pails, and making a cross in the air towards the cows’.

The Fairy Changeling

‘Come away, O human child / To the waters and the wild / With a fairy, hand in hand / For the world’s more full of weeping / Than you can understand’

Yeats, in his well-known poem ‘The Stolen Child’, reflects on a once common belief that fairies used to take human children, especially young babies, to their fairy abodes in the ringforts which dot the Irish landscape. Any human spirited away to fairyland and replaced by a fairy resembling him or her was called a changeling. The term most often applied to young children, usually babies, abducted by the good people who left wizened cranky creatures (fairy changelings) as substitutes. The mother always realised what had happened. Curiously only male infants were taken; the fairies waited until young girls had blossomed into womanhood and then selected the most beautiful. Some people claimed that fairies had power only over unbaptised children. Up to fifty years ago, in rural West Cork at least, babies were always baptised as soon as possible after birth, usually within two or three days. This possibly reflects a belief in changelings, but, most likely, was done because the Catholic Church claimed that an unbaptised person couldn’t enter Heaven.

Mothers used to take good care of their babies to prevent the fairies taking them: they blessed them with Holy Water, lit a candle near the cradle, prayed for their safety, hung a cross over the door. It was believed that a holy crucifix or iron thongs placed across the cradle would keep the fairies away. If a child was taken it was believed that he could be recovered by threatening to burn down the fairy fort. Another method was to tie a skein of black flax thread around the left hand, with a black-handled knife well gripped in the right. The thread kept one in contact with the human realm, while the power of the black-handled knife thwarted opposing fairy forces. The thread was tied to a briar outside the door of the fairy fort, and as one entered, the thread would unwind until one reached the kitchen, where the child would be found.

Placing a set of bagpipes by the cradle was a sure test to discover whether the child was a fairy. No changeling could resist them and soon fairy music spilled out of the house and into the village, thrilling all who heard it. Boiling egg shells was another way of detection. When a mother boiled egg shells in front of the suspected child, the changeling cackled with laughter in an old man’s voice, at the notion of making dinner from egg shells. To get rid of changelings it was recommended to force foxglove tea down his throat and wait until it burned out its intestines. No matter how hard the punishment of the fairy, the original child always returned unharmed.

It was said that no luck would come to a family in which there was a changeling as it drained away all the good fortune of the household. There was, however, a positive feature attached to the changeling which was an aptitude for music. As the changeling grew up it often started to play an instrument, usually the fiddle or pipes, with such skill that all who heard the music were entranced.

There are stories about young girls who were wanted as brides for a fairy king, so they appeared to droop and fade and die, but, in reality, had passed into the otherworld of the fairies. Sometimes young men were taken away by the fairies, especially if they were handsome, good athletes or good hurlers. They may have been needed to help the fairies in a battle or a hurling match. Lovely women in their prime were taken just for an evening to dance with the wild fairy, King Fionnvarra. Some were kept for seven years.

Changelings did not live long in the mortal world. They usually shrivelled up and died within the first two or three years. The changeling was mourned and buried, but if its grave was ever disturbed all that was found was a blackened stick or piece of bog-oak.

Although fairies jealously guarded their own songs and tunes, they travelled the world to listen to good mortal made music. Despite the fact that fairy abodes are very happy places with beautiful people and pleasant living, nevertheless, anyone who was allowed to return to mortal life gladly did so. In a story about Caoilte of the Fianna, it is said that he entered a fairy palace at Assaroe, near Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal, where he met his own foster brother and asked him how he liked living in the fairy palace. His brother replied: ‘Whether of meat or of raiment no item is wanting to us here, yet I had rather have the life of those who are worse off on earth than the life I live here’.