Ireland has reinvented itself in the twenty first century. It has emerged from the shadows and secrets of the 1900s. We have dismantled draconian laws against gay people. We have allowed literature and the arts to flourish when censorship forced some of our greatest writers to flee our shores like the ‘Wild Geese’. We have made, and continue to make, strides in rebalancing the former chasm between women and men. We have enshrined the rights of our children so we will never have industrial schools or Magdalene laundries again and all our children with additional needs can access education in a way that was unimaginable 20 years ago. Of course, we have more to do and striving for it is half the battle.

Twenty years on from the turn of the millennium, we also have changed as a people. Over a fifth of Irish people living in the Republic were born outside Ireland. The influx of so many different people has opened our minds, enriched our culture, and brought us face to face with racism. This is going to be the next step in our journey as a liberal and tolerant nation. The ‘Black Lives Matter’ global ripple effect has produced tidal waves in some countries. In Ireland it has made us confront a simple question – are we as tolerant as we think? More and more minority voices have spoken or written about their daily experiences of racism. Thankfully, we don’t have a situation like in the USA, or to a lesser extend in GB, where there is hostility and prejudice on an institutional scale and ingrained in the culture. Yet there is enough happening here to illustrate that some black, Asian and other people of colour have been victims of verbal, and sometimes racial abuse, in Irish society. Education remains our greatest tool against racism and schools have a major role to play in shaping the attitudes and behaviour of the next generation.

I have always understood that having a liberal society equates to tolerance, debate, respect for minority opinion and inclusivity. As we roll further into this millennium, I feel a shift in liberalism to mean that unless you are liberal, you are irrelevant. The first cracks of our newfound liberal society appeared when many who had opposing views on recent issues were made feel like pariahs. I gladly debated and discussed with people but, surely, when we try to close the argument down, can we call ourselves liberal?

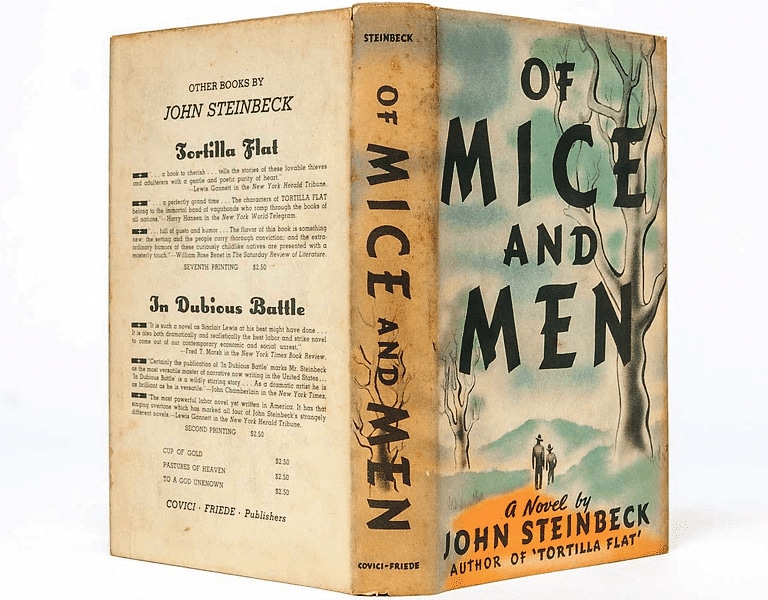

I have seen worrying trends again with recent calls for the banning of certain books on the Junior Cert course. Some parents have been lobbying the Department of Education to remove ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ (1960) by Harper Lee and ‘Of Mice and Men’ (1937) by John Steinbeck from the curriculum because the ’N’ word is used in them. While many readers are familiar with those books, those of you who are not should know they were written a few decades apart but during an era of institutional racism in the USA. Despite the fact that both books decry racism and have racist characters as the villains, does our newfound liberalism feel that any literature that uses the ’N’ word is unacceptable? This sentiment was echoed when Eamonn Ryan, leader of the Green Party, received abuse on social media for using the ’N’ word in the Dáil. The fact that Ryan used it in the context of highlighting racism and driving a debate for tolerance and anti-racism seemed to be secondary. Ryan apologised and tweeted, ‘I know this particular word should never be used.’ As I have often written in these pages, context is everything. So, is there ever a context for this word? According to some voices – never.

One thing we can all agree on is that whether one is for retaining or removing these books, we are essentially on the same side – anti-racism. It is the approach that differs. One side wants to ignore the book, the other to contextualise it. I stand firmly behind the latter. In ‘Mice and Men’ a black man called Crookes works on a ranch with the other men but lives in a segregated world. He cannot share the same quarters as the white workers, go to town with them, or even throw horseshoes with them in his leisure time. Steinbeck, as brilliant a fiction writer as he is, did not invent this; he merely mirrored what was going on around him in 1937. Being brave and principled about racism now is a hell of a lot easier than it would have been for Steinbeck in 1937, when the weight of the law and society was against you. The men who call Crookes the ’N’ word are the characters we are meant to despise in the book and, put simply, the word is part of the language of that era. This masterpiece is as much about man’s inhumanity to man or woman as it is about racism. The black man, Crookes, suffers prejudice; a woman, only ever referred as ‘Curley’s wife’, is married to a physically abusive misogynist; and Lenny, who has special needs, is misunderstood, scorned and a victim of mob justice. If we are censoring books because of words then we better get the bonfires going because there is a long list of books with all types of offensive words that are no longer PC today. To ban this book is to lose an opportunity to study a masterful writer who presents us with all the ills of society that make a marvellous launching pad for further exploration with children. It gives the debate context to tease out these complex issues with young impressionable minds. What also makes ‘Of Mice and Men’ and ‘To Kill a Mocking Bird’ great reads is not just their themes but that the writing is as accessible to teenagers as it is to adults, without losing any of the beauty, craft and depth to the prose. What is more, these books are optional and are part of an ever-increasing list that covers all sorts of issues and genres so teachers can vary their books from year to year.

It would be remiss of me not to point out the Achilles heel of my argument. As I mentioned, we live in a more cosmopolitan society, which means a lot of students are non-white. At the tender ages of 14 and 15 it will be difficult to hear these words. I have witnessed it. What is more, white people live in an echo chamber that for the most part makes us feel comfortable about our viewpoints. Last year, a class examined a caricature of Serena Williams smashing her racket in a tantrum when she failed to win a final. All agreed that the cartoonist did a good job in depicting a spoilt tennis player and a sore loser. All except two non-white pupils who saw much more. The caricature, like all caricatures aim to do with their subjects, exaggerated her features. For these two students these exaggerations were barefaced racism and not caricature. Period. The class soon went on to discuss the use of caricature of Irish people in ‘Punch’, a nineteenth century English magazine that portrayed Irish people with ape-like features. Their aim was to illustrate the relative primate nature of Irish people and justify colonialism. Words and images will resonate more with you if your race is the focal point of it.

However, I truly believe the contextualisation of these novels, and how teachers can use it to confront the issues, bear the greatest fruit – far richer that any initial discomfort. The same goes for gay or female students who study literature that uses derogatory terms for people’s sexual orientation or misogynistic terms. These terms are there [in educational literature] to capture the mores and prejudices in the themes and characters of these stories – not to insult readers. Fiction is reflecting society and society is sometimes ugly.

Let me end with one of the most inspirational people of the twentieth century – Muhammad Ali. He was athletic, courageous, charming, and intelligent. He had the world at his feet in 1967 – the heavyweight champion of the world. Ali lost it all when he refused to fight in Vietnam because of his principles. It didn’t make sense to him that black men [in disproportionate numbers] were fighting 10,000 miles away for a country that wouldn’t allow his kind to vote, or to be given fair opportunities to progress in life. When asked why he would not go, he responded to the interviewer with ‘’the enemy never call me n****r’’. To rewrite that sentence any other way than the way Ali wanted it reported, is to dilute the hatred, pain, suffering of black people encapsulated in that one simple word. It was, and still is, used to dehumanise the very nature of black people and Ali’s fight was in segregated USA not Vietnam. To rewrite that horrible word in a PC manner leaves the haters off the hook. In reporting it as intended was to allow Ali to shine a light on the racists that wanted him to wage their own colonial war, using economic slaves to fight it. Context is everything, especially when we are fighting the same battle.