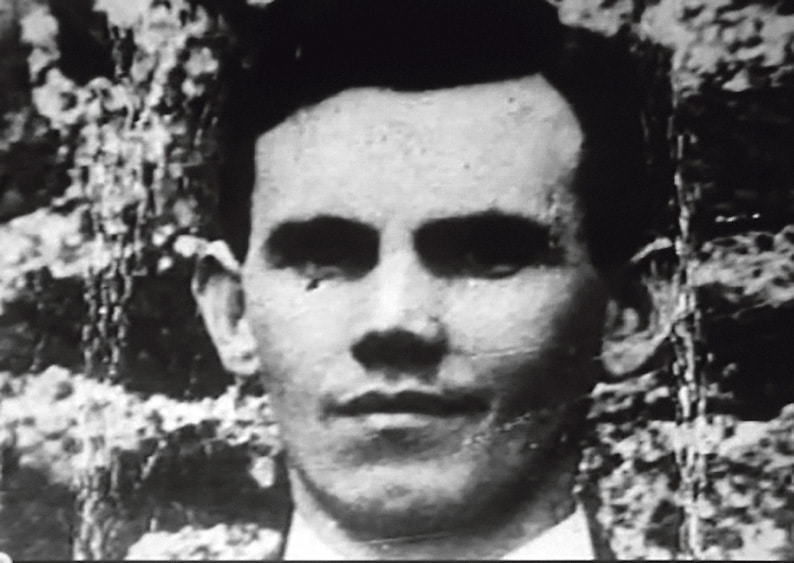

Photo : Desertserges man, Dick Barrett

One of the sound bites to emerge after the 2020 election is that the ‘old civil war politics is dead’. This reflected the emergence of Sinn Féin (SF) as a party equal in strength to the traditional big two, Fianna Fáil (FF) and Fine Gael (FG), who have dominated government in Ireland since its foundation. It was taken an indicator that young people in particular, were no longer willing to simply tick the ballot paper to reflect the historic voting patterns of their families and were willing to make a change. This week, I want to reflect on a great lecture given by historian Tom O’Neill, (author of The Battle of Clonmult) who spoke about the Civil War in his lecture to the Rosscarbery and District Historical Society. The organising of his lecture could not have been better timed, as we look to emerge from our civil war chains and its haunting ghosts.

On the first sitting of the thirty-third Dáil, the Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou MacDonald asserted that Fianna Fail and Fine Gael have run the country for a century and are unwilling to let go. Now it seems that a grand coalition involving FF and FG is a distinct possibility and therefore perhaps the end of civil war politics? Though the irony of FF and FG accusations of SF being undemocratic is not lost on people. For three years, southern politicians bemoaned, complained and pressurised SF to get back in to the Northern Executive and do business with the DUP. In this case, it didn’t seem to matter that those two parties are on the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of policies and political outlooks. The message was clear, suck it up and get on with it. Yet FF and FG are refusing to even talk to SF because of their differences? If the landscape of our politics has changed irrevocably from single party rule, then surely it is undemocratic to refuse to speak with, or even ignore, other parties? But here’s one to tease out. Micheál Martin told the whole country before the election that he would not consider entering a coalition with FG because he believed that the people wanted a change and that his party was unwilling to support Fine Gael in order to facility this change of government. He may still keep to his word. Yet for many observes, the two parties mirror each other in so many ways. If they do decide to go into coalition, then surely their identities will become fused?

When will we finally say that the past must no longer dictate our current emotions? If we hold onto the past too long, then Sinn Féin’s dark and somewhat murky history will forever weigh them down. Likewise, Fianna Fáil’s total mismanagement of the country, resulting in a complete economic collapse and loss of economic sovereignty, will always be a stick to beat them, despite personalities and policies changing. Will we look back in twenty years’ time and still punish FG for allowing, perhaps even facilitating an escalation of a country’s housing crisis so great, that a generation has been ruined? One hundred years later, since the foundation of the state, we can no longer look back and trade on the viciousness of the civil war that shaped our country’s affairs. So let’s reflect on Tom O’Neill’s insightful lecture about the civil war to understand what drove the FF and FG division a hundred years ago.

O’Neill’s lecture centres around Desertserges man, Dick Barrett, who was quarter master for the third Cork Brigade during the War of Independence. Barrett was an essential player in West Cork, procuring arms, fuel, and provisions to keep the brigade going. He also organised an Irish version of escape from Alcatraz, when he absconded from his imprisonment on Spike Island in November 1921. But Dick Barrett is probably best known outside of West Cork for more tragic reasons. He was one of four Republican prisoners executed by the Free State authorities on the 8th of December 1922. While there were many local atrocities on both sides in the civil war to fuel a generational hatred, none was so bigger that these executions. O’Neill gave us a background to their execution. In an attempt to quell the escalation of violence, The Free State arranged an amnesty, whereby anyone who had arms, could hand them over without retribution. However, after two weeks, anyone who was found with a gun that was to be used against the State could be executed. This was voted on in the Dáil and, as O’Neill explains, was quickly dubbed the ‘Murder Bill’. In response to this the Republicans decided to assassinate any TD who voted for the legislation. In another twist related to West Cork, Séan Hales – an elected TD from Ballinadee, who had fought with his brother Tom against the British in the War of Independence – was assassinated by the Republicans on account of him voting for that same Bill. For what was descending into more vicious hatred for each other, the Free States reprisal was quick. Four high profile Republican prisoners, one from each province, were chosen for execution: Liam Mellows from Connacht, Joe McKelvey from Ulster, Rory O’Connor from Leinster and Tom Barry from Munster. O’Neill explains that Barry was the most prominent prisoner they had from Munster, but he had made his escape before any of this came to light. Dick Barrett was seen as the next most prominent figure in the prison and so his fate was sealed. O’Neill also referred to Kevin O’Higgins, who signed the execution orders. His best man at his wedding some years before was Rory O’Connor. The four men were taken out at 8am to face the firing squad, only for more tragedy to occur. The soldiers had not been told whom they should aim for and most of the fire was trained on O’Conner; the result being, he died instantly, and the other three laying wounded and in agony on the ground. O’Neill explained that the soldiers had only one round, as is custom in a firing squad, so the officer in command had to ‘finish’ the men. Sickeningly, it took six more rounds to kill the men. O’Higgins stayed in politics, and while serving in the government as Minister of External Affairs, he was assassinated by the IRA in 1927. He couldn’t escape his past. Republicans blew up Free Staters outside Macroom, Free Staters blew up Republicans at Ballyseedy. It was murderous, repulsive and damaging and it led to civil war politics. It’s very easy to see how that generation was scarred and their differences irreconcilably linked to those events. It is less so today. It’s time to talk to everybody – so we can all move on from the past. Listen in to the history show on westcorkfm.ie.

On a side, Dunmore Golf Club is having a fundraiser at 7:45pm, on March 11at Dunmore House Hotel. I have been asked to give a lecture on the night about some of the topics in my book Behind the Wall –The Rise and Fall of Protestant Power in Bandon. The Key Note speaker on the night will be Doctor Paul Mac Cotter from UCC, an expert on medieval history, with a focus on West Cork for his lecture. Hope to see you there.