The Irish have always been notable travellers. A continental scholar, Walafrid Strabo, who lived over a thousand years ago, remarked that the Irish of his time were so given to wandering abroad that it was second nature to them. He had seen them coming by the shipload, monks and craftsmen and scholars, who were made welcome by kings and bishops and left a deep mark on religion and learning in Europe. There were others who turned their ships westward and northward, where they certainly discovered Iceland and, quite probably, reached what is now America, and returned to tell of the great ice islands, which floated on the sea; the tusked walrus and spouting whales, and the strange and wonderful adventures, which befell them on the magic islands of the great ocean. It is quite possible that St. Brendan, known as ‘The Navigator’, reached the Americas before the Vikings and Christopher Columbus.

Some years ago, the sailor Tim Severin and his crew, sailed the voyage they believed that Brendan had travelled in the same type of boat. He described his travels in his book ‘The Brendan Voyage’, proving that it was possible that Brendan, and probably others, could have reached America. Brendan is associated particularly with West Kerry, where Mount Brandon is named after him. There is a statue of him in Bantry, West Cork, where he looks out over Bantry Bay.

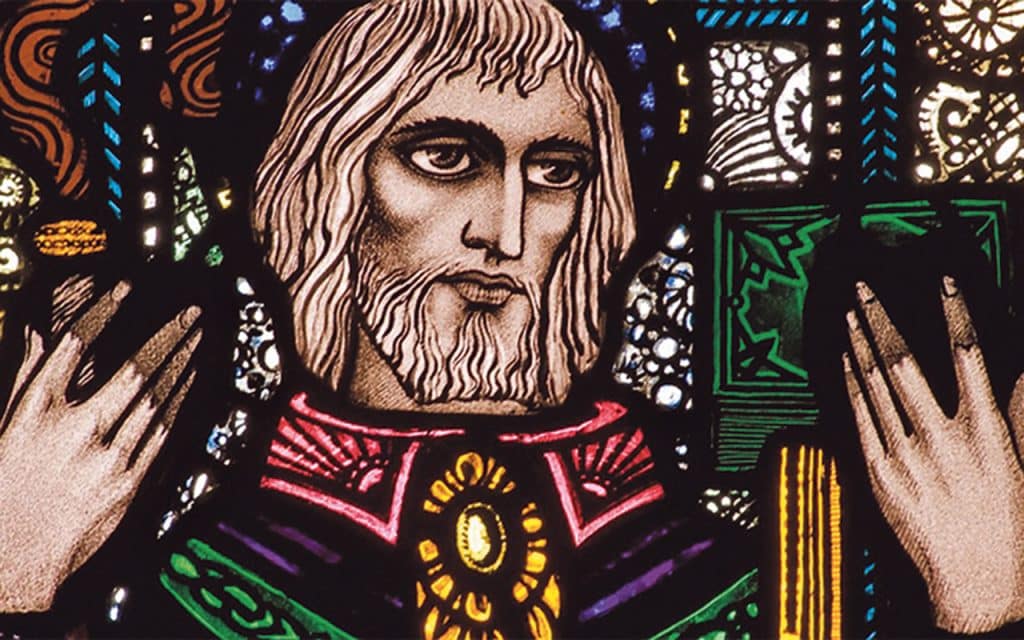

We can be sure that there were Irish men out and about long before the great days of the missionaries. King Dáithí is said to have been killed by lightning near the Alps. Irish raiders often snatched young people from the West coast of Britain and sold them into slavery. The most famous captive, of course, was Patrick. Unknown to themselves these raiders changed the course of Irish history and indeed the history of other parts of Europe. We know him, of course, as St. Patrick, our patron saint, who is given the most credit for bringing Christianity to Ireland. We know very little of these earlier wanderers. But since St. Colmcille (also known as Columba) left his beloved Derry and settled on the island of Iona off the west coast of Scotland, we can follow the course of the endless stream of Irishmen to all parts of the globe. St Colmcille preached Christianity in Scotland and after him, many other holy men travelled to Europe to spread the message of Christ. Famous missionaries of the period after St. Patrick, include St. Columbanus, who taught in France and Italy, where he established the famous monastery of Bobbio. St. Gall preached in Switzerland, where the town of St. Gallan is named after him. Other famous missionaries include Fiacre, Killian, Aodán, Fursey, and so on. St Fiachra, for example, preached in France. The site at St. Fiacre’s hermit cell became the nucleus of the great Abbey of Bereuil. The Fiacre horse-cab in France was named after him.

After the defeat of the Irish at the Battle of Kinsale (1601), a defeat that marked the beginning of the old Irish order, many of the Irish chieftains had to go into exile on the continent, mainly in Spain, France and Italy. The Northern chiefs, O’Neill, O’Donnell, Maguire and others found refuge in Europe. The West Cork chieftains, principally O’Driscoll, O’Mahony and O’Sullivan, had to leave. Many of them joined the armies of France, Spain and other European countries. Many of the Irish soldiers left after the defeat of King James by William of Orange. This event is known as the ‘Flight of the Wild Geese’. A few of the more famous were Lally, O’Mahony and, of course, Patrick Sarsfield, who died at the battle of Landon fighting for the French against the old enemy, England. It is said that his last words, as he saw his life-blood flowing away, were: ‘Would that this were for Ireland’.

As well as travelling abroad, people were moving about the home island too. Travel is so fast nowadays, getting to the destination as fast as possible is what interests most of us. In the old days it was different, the journey was interesting and exciting of itself and the wise traveller set out himself to enjoy every minute of it. Besides that there were many classes of people whose livelihood depended upon their moving from place to place. Take for instance, the bands of poets who imposed themselves on the kings and chieftains, eating a chief or nobleman out of house and home and then passing on to the next hospitable house with extravagant demands for bigger and better hospitality. If anyone refused their demands they composed satires on them – funny and malicious songs that were spread about from person to person to the eternal shame of the victim. No wonder that the chiefs of Ireland rose against them in the end and would have driven them out of the country, but for the intervention of St. Colmcille, himself a poet, who returned from Scotland to speak on the poets’ behalf and begged permission for them to stay, under promise of less demands.

Once upon a time there was a Corkman who vowed that he would never rest until he reached the end of the world. And so he travelled many a weary mile over land and sea until finally he reached a great wall that reached nearly to the sky. Up he climbed from crevice to crevice with his heart in his mouth until, at the very top, he found a Kerryman calmly seated, smoking his pipe and gazing wistfully into the intimate space beyond. This jocose story illustrates the Irish people’s love of travel.

In Irish folklore there is a well-known folk tale about a scholar named Mac Con Glinne. The story starts like this: ‘A great longing seized the mind of the scholar to follow poetry and to abandon his studies for he was tired of studying. This came into his mind on a Saturday night at Roscommon. So he sold what little belongings he had for two wheaten cakes and a cut of old bacon, which he put in his book-bag. And he shaped for himself on the same night, a pair of shoes of seven thicknesses of soft leather, and set out next day on his travels, finally saving the king of Munster from a hunger-demon, which gave him an insatiable hunger. He became rich and famous’.

In the penal times, when it was almost impossible to get any kind of education, there were many poor scholars on the road. If any of them heard of a good teacher, a priest, or a hedge- schoolmaster, he made his way to where the teacher lived, and began to study under him, working for a farmer and teaching the ABC to farmer’s children for his keep. Here in West Cork, the famous poet, Séan Ó Coileáin, had a famous school near Myross in Union Hall. Many scholars came from the neighbouring parishes to learn from him.

There were wandering musicians and ballad singers who went from fair to fair, sure of a night’s hospitality because of their art. Some of the became famous, like the great Turloch Ó Carolan, ‘the last of the bards’, who was a wonderful harper and composer of many fine tunes. Many of these were kept alive in memory and were taken down by music collectors like Canon Goodman. He and his like were made welcome at the houses of the gentry, not only the noble of the old Irish stock, but the newer landowners settled by Cromwell and King William of Orange. There were many notable pipers too and the fashionable gentlemen learned to play the pipes from them.

There were also travelling storytellers and they too were sure of a welcome. A person who couldn’t tell a story, sing or play an instrument, wasn’t as welcome as those who could. There is a tale of a poor simple fellow who had no song or story, and so was refused lodging at every house until he came to the house of a man who was ‘in league with the fairies’. The poor boy was given a bed, but he slept little. He spent the whole night in terror of corpses, coffins, graves and threats of horrible men. When the morning came, the man of the house said, in a kindly way, ‘Now boy, you’ll never again be refused a lodging, for you have a fine long story to tell after the night’.

Within the memory of our great grandparents, or later, there were many craftsmen on the roads, journeymen coopers, smiths, carpenters, saddlers, shoemakers, stonemasons and others. Tailors came and stayed in the house until all the clothes needed by the family were made; then they passed on to the next house. Wherever there was a big house or a church being built, you might see travelling stonemasons arriving and greeting the chief mason in the secret language of the craft. ‘Airing a soistiriú (a travelling mason) Muintria airig! Coistgrig éis!’ (God bless you mason, come in, boy.’) Sculptors and stone cutters went from job to job in the same way.

Another big section of wandering people was made up of the spailpíní, the migrating labourers from the western counties into Leinster, East Munster and East Ulster. In the spring, they came to the hiring fairs with the long spades over their shoulders, and in the autumn with their reaping hooks and scythes. Often they worked for the same farmer every year and the sons went to the same farms as their fathers. In the north-west, Donegal and Mayo particularly, the labourers or small farmers crossed to Scotland to find work on the big farms there. For example, the father of the popular singer, Daniel O’Donnell, spent about 10 months of every year, labouring in Scotland. This put great strain on the mothers who had to raise their families practically on their own. In Scotland and also in parts of northern England, their strength and skill, their music and merriment were highly valued.