The Realism Now exhibition, currently showing in Barcelona’s MEAM Museum, showcases some of the world’s best contemporary figurative painters. Amongst them is the British painter, Edward Povey (b.1951), whose extraordinary brand of ‘emotional realism’ (the artist’s term) both resonates and extends the Western tradition, intimating and echoing painters as far back as the Dutchman, Pieter Aertsen (1508-1575). Aersten was one of the first painters to combine still life and genre painting. His lively, compressed compositions, with still life articles and figures juxtaposed at often awkward angles, provide an interesting antecedent for Povey, whose larger than life figures, teacups, glasses and spoons dwarf their erstwhile models.

Povey, who hales from Wales, is a master of composition. Of course, one might say that composition is at the heart of art’s mystery, therefore a great artist, it goes without saying, is a great composer. I have a formula which I have written about before and will state here again: Composition is the Source, Vibration is the Spirit, and Illusion is the Dream: the source of all power is composition, the spirit of all expression is vibration, and the dream of all reality is illusion. When all three elements are present to a high degree in an image, it will resonate and echo in the mind of the viewer for a very long time. And so it is with the work of Edward Povey. The compositions, the arrangements are exemplary: a sliver of black and white floor tiles, the placement of silverware on a face, the angle of an arm, the direction of a gaze: all of the elements in Povey’s works conjure a whole, closed-in, yet mysteriously clear matrix, made all the more powerful by the painter’s almost forensic, yet painterly, command of realistic form, his effective balance of tone, and his use of multi-perspectival planes.

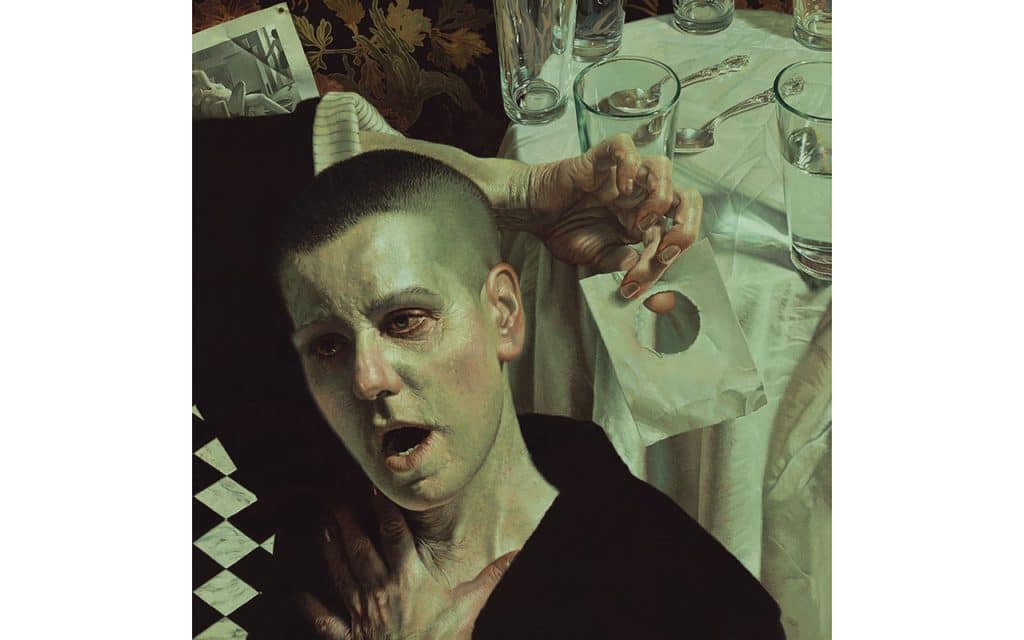

‘Nabokov’s Window’ (2020) and ‘Congédiement’ (2022) are both rich examples of Povey’s compositional and painterly programme. Their aggregation of intriguing symbols, their formal arrangements, utilising two simultaneous perspectives (resonant of Cezanne), their employment of Raphael’s Verdaccio (green-red) palette, the mood of the figures, and their scale, present puzzles of meaning, which at the same time flow with non-verbal feeling and aesthetic power. This harmonic yet pensive quietude, underscored by a hidden, and one senses, painful, narrative is quintessential Povey. There is, one feels, a brokenness behind the red-rimmed eyes of his figures, made all the more stark by their juxtaposition with gleaming silverware and sparkling clean porcelain.

‘Nabokov’s Window’ is a square composition (200x200cm), roughly divided along a diagonal line between the bottom right corner and the upper left corner, with the shaved head, arm and shoulders of a woman in the left division, and a tableau of glasses, silverware, table and wallpaper in the right. The woman’s right hand reaches behind her head, snaking into the right division, and holds a piece of paper with a circle cut into it, possibly an allusion to the title. The woman’s left hand is circled protectively around her throat, her mouth is open, and her red-rimmed eyes stare, as if into her past, out of the picture plane.

In the top left corner, above the woman’s forearm, we see a segment of a reproduction of a painting by Balthus (1908-2001), titled ‘Nude with a Cat,’ (1949) ‘pinned’ to the fictive wall. In the bottom left, between the woman’s arm and the edge we see a segment of black and white checkered floor tiles. The woman is presented front on, the table and floor slightly from above, and far too high in respect to the figure. This is Povey’s simultaneous double-perspective in action, a visual double-take which, because of the seamless harmony of all the shapes, leaves the viewer beguiled, but untroubled.

The Balthus reproduction offers, perhaps, a clue to the hidden narrative. ‘Nude with a Cat’ depicts a young, naked girl in an erotically charged pose, a stream of window light falling upon her. The card with the cut hole, held behind the woman’s head, is–as Povey himself points out–where she can’t see it; a window to a past, perhaps, she would rather not confront. Whatever that past is, there is a poignancy here between the youth and awakening of a bygone Balthus model and Povey’s pained middle-aged figure. There is also a contrast between Balthus’ innocent adolescent muse and Povey’s own subject, experienced and hurt by life’s travails. Povey is wise enough to leave the clues there; possibly he does not know more than this himself, the act of creation being a mysterious one, where one form evokes another, gradually forming a subconscious puzzle of resonances and allusions. There is, however, one more layer to Povey’s quotation of Balthus. The French-Swiss painter was also a great composer of forms, incorporating checkered tiles and carpet designs into his painterly tableaux. And so ‘Nabokov’s Window’ is perhaps, at once a narrative of hidden trauma and a tribute to a painter, whose compositional strategies Povey has clearly absorbed.

‘Congédiement,’ like ‘Nabokov’s Window,’ presents a close-up of a woman with a shaved head, a round table setting, and a background of patterned tiles. The division this time is between lower and upper halves, with the woman shown front on in the lower half, and the table and tiles shown from almost directly above, in the upper section. The simultaneous disjuncture and harmony of perspectives is arresting, giving the composition an immediate graphic power.

The woman’s left hand clutches at her deep V collar, pulling it aside to show her chest. Her right hand, held vertically straight, touches her head, which is bent horizontally to the viewer’s left. Between her fingers is a letter. Above the arc of her head and neck is the white round table, complete with tea cup and another letter (or part of the same one) soaking in a bowl. A strip of meat bleeds into the tea-filled saucer in which the tea cup is sitting. The strap of a bra angles out from under the table toward the top left corner.

Like ‘Nabokov’s Window’ it is an extraordinary painting, both full of density of form, and depth of emotion; its tonal pitch equals its emotional one, the white of her collar luminous against the black night of her dress, the slightly sickly reds and greens of her skin a nod to the white-greens of the table cloth and the dark red-browns of the tea and ground. The main clue to the hidden narrative is once more in the title; ‘congédiement’ means ‘dismissal’ in Italian. Povey offers more of an explanation here, stating that the letters are “from an Israeli songwriter, written to a young lover who was being dismissed.” That being said, the image holds a deep universality, able to conjure a myriad of possible narratives. To such a resonant painting the viewer might bring their own story, held as they are by the circularity of visual melodies and emotions, which echo for a long time in the mind.

Edward Povey’s paintings hang in art collections in 27 countries. For more of his work visit www.edwardpovey.com, or on Instagram: edwardpovey