The shape of things

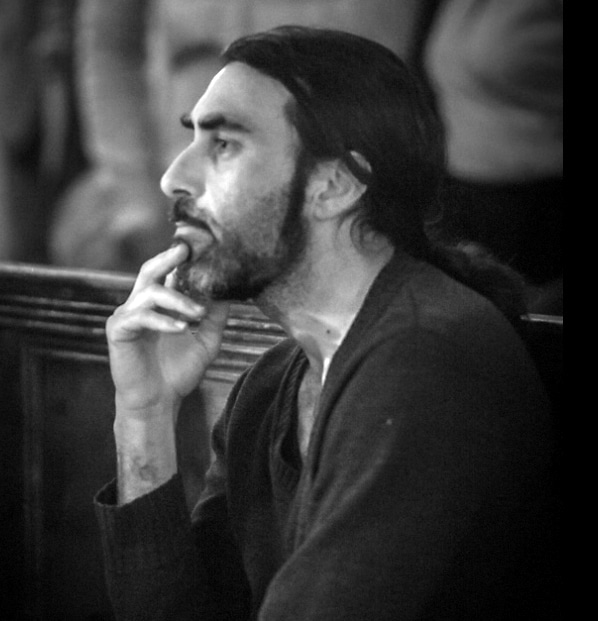

James Waller is an Australian born artist and poet based in West Cork. Through this column James explores the world of art, introducing the reader to major works of art and artists and reflecting on what makes them so engaging.

James offers a range of studio-based courses for children and adults in Classical painting, drawing and printmaking at Clonakilty School of Painting. See www.paintingschool.

jameswaller.org for details.

Luminous green lichen sheathes the alder, like an exoskeleton of armoured plates and horns. Diamonds of water drip from the straggle of branches, wavering towards me as I look through the window pane. These past two months have been, for me, a time of poetry, of both writing it and reading it, and it is with some effort that I pull myself toward the more analytical task of writing about art. So forgive me if I enter this task via the first ten lines of a poem:

If the world ran out of fire / I would hold it in my pen / Like Breughel’s Mad Griet / Scared in the Flemish haze / Sword glinting in the spider’s harp / A compression of sounds floating through organic hell / Whose eyebrows seat incalculable birds / And into whose mouth / Float the debris / Of infernal humanity’s wounds…

The imagery in this poem (‘A Rain of Blood’, published in my book, ‘Insomnia’s Gates’) refers to a painting by Pieter Breughel the Elder, from 1563, titled ‘Dulle Griet’ (Mad Meg). It is a painting which has haunted me ever since I first saw it in the Rubenshuis in Antwerp, in 1997.

As an object the painting has undergone a journey worthy of a novel. It was looted by Swedish troops in 1648, from the collection of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, re-emerged in Stockholm in 1800, and was subsequently discovered by Fritz Mayer van den Bergh in 1897 at an auction in Cologne. It now resides in the Fritz Mayer van den Bergh Museum in Antwerp, Belgium.

The painting depicts Dulle Griet, armoured, with sword in one hand and treasure in the other, storming, with an army of women, the mouth of hell. The women, in peasant dress, are fighting Bosch-inspired, hybrid creatures, part animal, part human, against a fire-lit landscape where devils can be seen dancing and where a giant spider plays a harp as it emerges from an egg.

The composition is constructed like an envelope, with four main triangular sections, countered and enriched by a dizzying array of curvilinear rhythms, all set to a palette of red, black, yellow ochre and white. There are hardly any vertical or horizontal lines, meaning everything is tipped. The depth of field is shallow, the action omni-directional, the neutral colours allowing the yellow ochres and crimsons to glow. The brilliance of the composition, its imaginative fire, is what makes it so powerful.

There is much speculation, however, over the meaning of the work. When viewed in the context of contemporaneous Flemish literature it reads as an allegory about “noisy and boisterous women”, reflecting , perhaps, a wider male anxiety about women with power. According to one Flemish proverb, “One woman makes a din, two women a lot of trouble, three an annual market, four a quarrel, five an army, and against six the Devil himself has no weapon”. In another popular proverb we appear to find the source of Breughel’s theme: “She could plunder in front of hell and return unscathed.”

Dulle Griet (Mad Meg) would appear, in the historical context, therefore, to be a subject of caution, ridicule and mockery. This reading is reinforced by Breughel’s well-documented use of proverbs for other works of the period, including the painting, ‘Netherlandish Proverbs’ (1559), and fits with a wider cultural practice of illustrating pithy sayings.

‘Mad Meg’, it appears, is no Joan of Arc, but a subject of satire for a culture which burned women at the stake for revealing any kind of strength or knowledge. There is a flip-side, however, a certain ambiguity and ambivalence, both in the painting and in its possible literary sources. There is, firstly, some ambiguity in the proverbs, which may indicate either folly, courage or both. ‘Mad Meg’, herself is depicted as a powerful figure, hinging diagonally on the fulcrum of the composition. In the midst of chaos and conflict there she is, whom they call the mad one, armed and armoured, holding the treasures of humanity against the fires of hell. She is a plain, peasant woman, yet she alone in the scene exudes human strength. This is what has always struck me; that the satirised anti-heroine may become, in a heartbeat, the heroine, a female saviour of humanity, a force of strength in the midst of breakdown and disorder.

Ultimately Dulle Griet is, for me, an emblem of war, of order striving against chaos, of good versus evil. For this reason Breughel’s painted fires have once more entered my poetry:

That is the footprint of Europe, amidst cupolas / And spires, bronze patinas and stained glass churches / It wavers with the beauty of a winter landscape, / Paints itself into states of ineffable grace / Then steps into the darkness. Its embers are flaring / In the East, like in the burning landscape of Breughel’s / Dulle Griet, in which ‘Mad Meg’ storms the gates of hell, Sword in one hand, a hoard of gold and silver in the other / I always wondered why they called her the mad one.

On its journey from studio and palace to galley and auction house, through all the vicissitudes of war, Dulle Griet, has survived, both as a painting and an idea, as a fictional anti-heroine – come heroine, as a fragile painting on panel, defying destruction. To have come, unscathed, through what it depicts is yet another irony of its singular existence.