There are many animals that reach a great age. Tortoises and turtles are especially long-lived. In his lovely 1948 book ‘Over the Reefs’, Cork-born writer and artist Robert Gibbings (whose father was rector of St. Multose Church in Kinsale) told of a radiated tortoise called Tu’i Malila that lived as a member of the Tongan royal household. It was supposedly brought from Madagascar to Tonga by Captain Cook in 1777, so it was at least 171 when Gibbings’s book was published. It died in 1966.

Then there was Adwaita, a giant tortoise from Aldabra in the Seychelles, that was given to Robert Clive (of India) in the 1750s. It died in 2006, making it over 250.

Greenland sharks, enormous fish up to seven metres long that live in very deep, cold waters in the North Atlantic, can be even older. In a 2016 study using radiocarbon dating of the lenses in its eyes, a Greenland shark was found to have been born between 1504 and 1744, making it, at the lowest estimate of 272, the oldest of all vertebrates.

But there are more humble creatures that can, theoretically, live forever.

Jellyfish and their relatives are, after sponges, the most primitive of animals. Their fossil record goes back to Pre-Cambrian times, over 530 million years ago. They usually have a short lifespan – from a few days to a couple of years, depending on the species. They belong to the phylum Cnidaria, the diagnostic feature of which is the possession of stinging cells on their tentacles. These cells are like microscopic bags, each containing a coiled rope attached to a barbed harpoon. When the tentacle touches something – food or swimmer – the harpoon is ejected, stabbing and sticking to the possible meal, and injecting venom.

There are three classes in this phylum: the Anthozoa, which are the sea anemones and corals; the Scyphozoa, the true jellyfish; and the Hydrozoa, a diverse group of animals which range in size and complexity from the tiny freshwater Hydra to the dreaded Portuguese man o’war.

Cnidarians typically have two stages in their life cycles – a polyp and a medusa – though in some groups, one of them might be absent. The polyp is usually fixed in some way to the sea bed. A sea anemone is a solitary polyp, while a coral reef is made up of thousands of very small polyps all living together as a colony embedded in a calcareous skeleton. A medusa is a sort of upside-down polyp that swims; a jellyfish is a medusa.

A typical jellyfish starts life as an egg, which develops into a larva called a planula. This swims around until it finds somewhere suitable to settle, whereupon it sticks to the substrate and grows into a polyp called a scyphistoma, which looks vaguely like a tiny sea anemone. This polyp reproduces asexually by a process called strobilation – its upper surface divides and divides, producing a series of flat buds on top of one another, like a stack of pancakes. Eventually, these separate and swim off into the plankton as miniature jellyfish called ephyra, which mature into the sexually-reproductive, male or female, adult jellyfish.

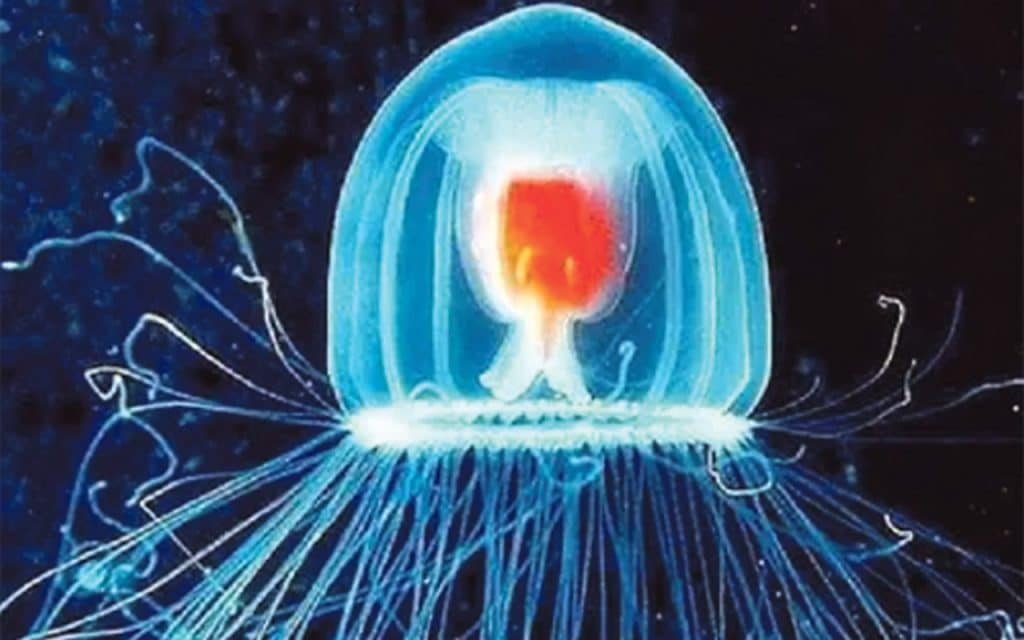

Research in Italy in the 1990s found that a tiny hydrozoan, Turritopsis nutricula, under conditions of environmental stress, was able to reverse this life cycle. The medusa stage (usually no more than three or four millimetres across), instead of reproducing sexually, could return to the sea bed and change back into a polyp. In 2015, researchers in China found something similar happened in the common jellyfish, Aurelia aurita.

This means that whenever life is not going too well – the animal is damaged or there is not enough food to grow and reproduce sexually – it can go back to the sea floor and rest a while until things are better, then start budding off little pancakes again. In theory, this could go on indefinitely, so the jellyfish could be called biologically immortal.

In reality, of course, immortality is highly unlikely. Jellyfish are very fragile, and have many predators – notably sea turtles which, tragically, are unable to tell a large jellyfish from a plastic bag – so they would almost certainly be eaten, or washed onto the shore, or sucked up into the cooling system of a fishing boat and destroyed, long before they reach the end of their natural lives.

In Ireland, we have five species of true jellyfish. The best known is Aurelia, easily identified by the four purple-coloured gonads at its centre. Then there is Chrysaora hysoscella, the compass jellyfish, so called because of the brown lines radiating from its centre, like the points on a compass.

There are two species of Cyanea – the blue jellyfish, C. lamarckii, and the fearsome lion’s mane jellyfish, C. capillata. The latter are orangey in colour, and around our shores, usually no more than 20 cm across. But in deeper water, they can reach two metres in diameter, with tentacles 30 metres long.

Finally there is Rhizostoma pulmo, the barrel jellyfish, a grey, lumpy animal with no real tentacles, that grows up to a metre in diameter. It can occur in enormous blooms, which often cause big problems for fishermen. When I was on a cruise aboard the research ship Lough Beltra in the Irish Sea in 1988, one haul of the net was totally filled with hundreds and hundreds of these huge jellyfish.

Most hydrozoans are so small, few people are aware of their existence. You might see tufts of something plant-like growing on a piece of seaweed – they are probably hydrozoan polyps. The medusae of such polyps resemble Turritella, and are too small to see without a microscope. There is, however, one large hydrozoan jellyfish that occasionally washes up on our beaches – Aequorea vitrina, the crystal jellyfish, which is, as its name implies, as transparent and delicate as a piece of glass.

Two other jellyfish-like creatures are often stranded on our beaches. Velella velella, the By-the-wind-sailor, resembles a small, oval piece of blue plastic, with a triangular sail. It is harmless. The Portuguese man o’ war, however, can give a severe sting; if you find a pinkish-blue bubble-like thing with a tangle of blue tentacles, do not touch it.

Stings from the other jellyfish you might meet are not usually serious, except to those allergic. Contact with Aurelia is like touching a nettle, but C. capillata can be more dangerous and should be avoided. If you do get stung, apply vinegar as this deactivates the stinging cells. We are fortunate in Ireland not to have any box jellyfish; their stings are very powerful – in Australia, one species of box jellyfish has caused 79 fatalities since 1883.

Jellyfish are eaten by humans in the orient. In China, I once bought a packet of dried jellyfish, just for the experience. I followed the badly translated cooking instructions, but the jellyfish mostly evaporated into nothing but a few stringy bits of tasteless tentacle.

So if you find a jellyfish washed up on the shore, it is probably best not to carry it home for supper. But take a good look at it, admire its strange beauty, identify it. Then try, as I always do, to return it, carefully, to the water. I find their soft, smooth bodies are strangely pleasing to the touch (avoid contact with the tentacles, of course). Jellyfish are not endangered by human activities – indeed, their numbers, according to a survey last year, are increasing, perhaps due to global warming – but giving a fellow creature a helping hand, even if it is probably a futile one, always makes me feel good. If the jellyfish does start to move, its glassy bell pulsating again as it heads off back into the ocean, then you will have saved one life, perhaps given it a chance to reproduce and pass on its DNA to another generation. It might even supply lunch to an old sea turtle.