Séan Ó Súilleabhain, in his book ‘Caitheam Aimsire ar Thóraimh’ (translated as ‘Irish Wake Amusements’) describes the customs attached to waking the dead in Ireland. The title is startling in that we don’t associate a wake with pastimes or call it merry. Ó Súilleabhain noted that wakes were “far merrier than weddings, with the young people looking forward to the death of an old man or woman so as to provide them a night of turf-throwing and frivolity’.

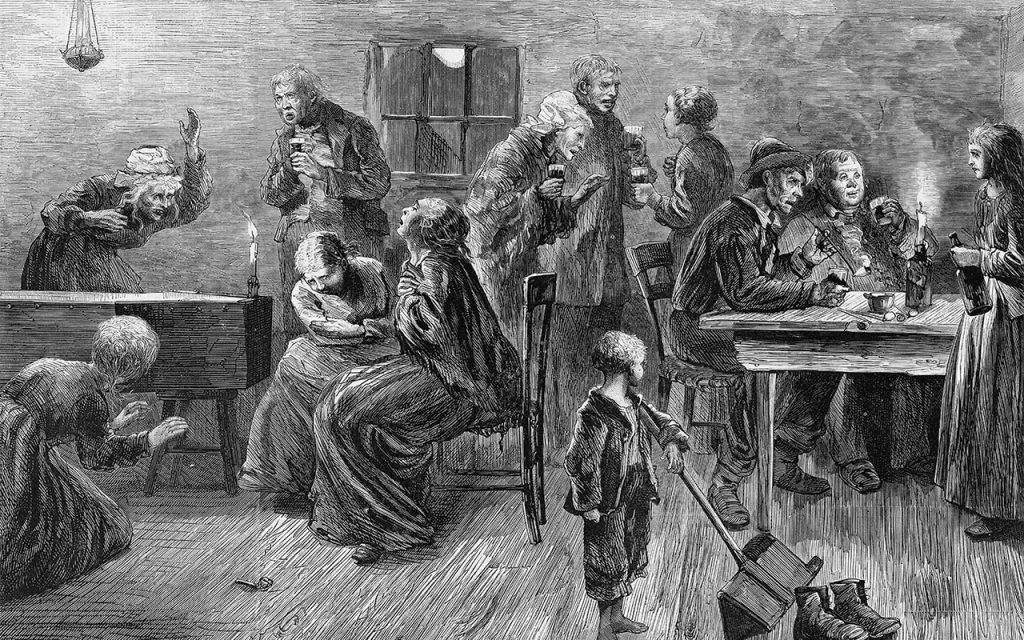

Nowadays, the wake is a solemn occasion and the purpose of a visit to the wake is to pray for the dead and to sympathise with the relatives of the dead person. According to Webster’s Dictionary, “to wake the dead is an observation of the deceased’s body in the period between death and burial”. A wake consists of relations and friends of the deceased gathering together for the sole purpose of consoling one another for their loss. The term ‘merry wake’ refers to those wakes where merry-making and frivolity, as well as music, dance, games, story-telling and other amusements took place in foreign times.

In my youth there was great respect for the dead. If the hearse passed through a town or village, the shopkeepers pulled down the blinds and closed the shop door while the procession was passing. If you were driving a car, you never passed the procession but took a side road or followed the line of cars. When news of a death in the townland spread, all work in the fields stopped and implements were abandoned as a mark of respect.

Usually the body was waked in the house until it was taken to the church on the eve of the burial. Up to recent times ritualistic cleaning, shaving and preparation for the ‘laying out’ of the corpse took place, done by customary individuals (often old women) in a prescribed traditional manner. Usually, a crucifix was placed on the breast of the deceased and rosary beads intertwined in the fingers. Supplies of food and drink were obtained to share with the mourners.

During the wake, tobacco and clay pipes were offered to the men and snuff was made available for the ladies. ‘Mná caointe’ (keening women) wailed their sorrowful verses over the corpse. In places there were professional keeners. All clocks were stopped, soon after the person had died; mirrors were covered. When the coffin was being taken to the church, it was placed on two chairs outside the front door. When it was placed on the shoulders of the bearers, the chairs were knocked over and remained that way until after the funeral.

It is necessary to emphasise that a ‘merry-wake’ was only had on the death of a fully-aged adult whose death was expected. If a tragic or ‘untimely’ death were to occur, the wake was a very solemn affair with intense keening for the dead. Although keens (from the Irish word ‘caoineadh’, to cry, lament) was generally done by women, there are records of fathers keening for a dead child, husbands keening for deceased wives.

The wake games, the origins of which go back to pre-Christian Ireland, died out in the 19th century when the clergy spoke and acted against them as being ‘pagan’ and ‘disrespectful’. But they were never meant to show anything other than respect for the dead in the ancient way, and like so many other beliefs and practices, they should be judged according to the standard of the time and not by those of our modern age

Kevin Danaher, in his book ‘In Ireland Long Ago’, lists and explains some of these wake games. A typical one, he writes, was ‘The Bees and the Honey’, in which an innocent ‘gom’ (foolish person) was chosen as the hive and seated on a stool in the middle; he was then covered with straw and the ‘bees’ – other young men – buzzed around searching for honey. Each bee took a big mouthful of water and all together spilled their mouthfuls into the hive, thus soaking the poor wretch under the straw. Another was ‘The Horse Fair’ in which a number of boys and young men were ‘horses’ being put through their paces by a ‘dealer’, who called them appropriate names i.e. a tall boy could be called ‘the racehorse’ and a stout youth ‘the cob’, a big rough fellow the ‘shire’ and an active young fellow the ‘colt’. The dealer made them show off tricks of running and jumping; if one failed, he was beaten by the dealer or made to lie on the floor, while another player, the blacksmith, hammered the soles of his feet. Other games included ‘Hunt the Slipper’, ‘Forfeits’, ‘The Priest of the Parish’, ‘Buying the Oats’, ‘Fronsey Fronsey’, ‘Hot Hands’, ‘Fool in the Middle’, ‘Selling the Pig’, ‘The Poloney Man’ and many more. These sound ridiculous to us today, but perhaps a century hence many of our current beliefs and actions will probably be looked on in a similar vein.