The heritage council defines traditional buildings as those constructed before World War II. There are estimated to be 270,000 traditional buildings in Ireland that were built prior to 1945. A traditional building doesn’t necessarily indicate that the property is of particular architectural or historical merit (i.e a listed or protected structure) It is determined by age of the structure and the kind of materials it was built with; solid stone or rubble walls with lime renders, single glazed windows and a timber roof structure. So, a farm house built in the 1900s falls into this category and we have plenty of examples of these around West Cork.

With the introduction of the vacant and derelict property grants in 2022, more and more of these older buildings are being refurbished and retrofitted to bring them back into use. When retrofitting these kind of homes, attention needs to be given to the kind of materials and techniques used. Modern materials and methods are not always appropriate, particularly when dealing with the walls.

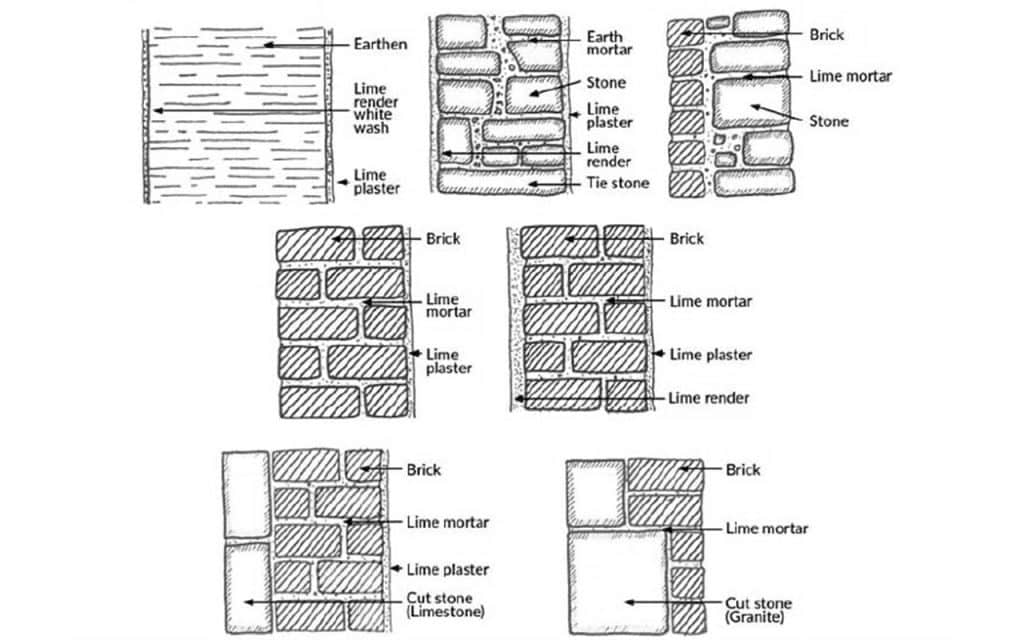

Traditional solid walls have quite a clever way to deal with moisture. They are constructed of permeable materials, such as stone with lime mortar joints and a permeable lime plaster internally, for example. Here is how they process moisture: when it rains, the external surface of the wall draws in liquid water through the porous structure, which is then distributed throughout the wall. As the rain stops and the sun shines, or as heat passes through the wall from the inside, this rain evaporates out of the wall.

Internally, excessive water vapour can pass through the permeable structure to reach the outside or can be temporarily stored in the hygroscopic lime plaster and evaporated back to the room once the inside relative humidity level drops. In the past, the burning of an open fire from Autumn through to Spring, ensured the surfaces were kept warm and the leaky construction of the buildings allowed drafts to keep the buildings well ventilated. This ensured the solid walls of traditional buildings were kept relatively dry. By comparison, a modern cavity wall works very differently and is designed to prevent moisture from entering or exiting the building altogether with the use of impervious non-breathable materials and a cavity break in the middle. In fact, the gap in a cavity wall was only originally added to prevent moisture movement through the wall, adding insulation to this cavity came later.

When insulating solid walls, the addition of external wall insulation, (EWI) is relatively safe. The insulation and new render coat act as a protective layer, keeping the original wall dry and warm. With this method of insulation, problems are unlikely to occur, when done correctly. However, adding internal wall insulation, (IWI) to a solid wall is not without its complications, particularly with modern solutions. One of the major concerns is how the IWI will affect the existing wall’s ability to deal with moisture, both internally and externally. This additional insulation will inhibit the walls breathability and reduce the drying capacity, creating a cold surface behind the insulation. This can lead to an increase of moisture within the existing wall, which can in turn bring potential problems such as external cracking of the existing wall due to freeze-thaw, corrosion of timber or metal components within the wall, interstitial condensation and mould growth. The fact that many of these walls may have been ‘renovated’ with cement-based renders over the years makes the problems worse.

In order to minimise the risks when upgrading these older walls with IWI, breathable materials are often used. The use of lime plaster and wood fibre insulation, for example, maintain the original moisture function of the wall. The target level of insulation may also be reduced. The reasoning behind this concept is to still allow some heat to pass through, helping to keep the wall dry. Adequate ventilation of the building is also crucial.

One of the considerations with these materials and methods, is that they are generally more expensive than modern solutions and, until recently, it was not possible to access the SEAI grants. The SEAI grant criteria requires insulation ‘systems’ with National Standards Authority of Ireland, (NSAI) approvals, which none of these breathable materials have and the u-values (level of insulation) required would be impractical to achieve with natural breathable materials.

At the end of last year, SEAI launched a Traditional Building Retrofit Pilot to address these shortcomings. The pilot is run through the existing One Stop Shop, (OSS) framework and will ultimately lead to the development of a new stream of grants. For now, the levels of funding available for an upgrade under the pilot will be the same as the normal OSS offering, but there is a relaxation on some of the criteria. For example, wall insulation materials without an NSAI certificate can now be used and the target level of insulation, (u-value) is relaxed. This means that you could upgrade a solid wall with hemp, lime, woodfibre, and so on, and still benefit from the internal wall insulation grant. A grant towards secondary glazing is also possible. In certain situations, the requirement to meet a minimum B2 BER rating may also be relaxed, on a case by case basis. If you would like to join the pilot you will need to contact a registered One Stop Shop and you will also need to appoint a traditional building professional to specify the materials used in your upgrade, (an engineer, architect or building surveyor specialist in conservation)

If you would like to get in touch about anything in this article or your own retrofit project, feel free to reach out; ruairi@retrofurb.ie.