The work of printmaker, Brian Lalor, as viewed in the current Uillin retrospective, reveals a Janus-faced graphic artist of, on one side, Bruegelian humour, intensity and detail, and on the other, expressionist fervour and flight. Breaking this down further, in his tighter drawings of cityscapes we glimpse an architect and archeologist (both former professions), concerned with records of structure and place; in his conte drawings we discover a neo-expressionist, crackling with the dark days of the Troubles; in his looser etchings we encounter a Bruegelian myth maker, and in his linocuts and woodcuts a pure poet of line. It is a testament to Vera Ryan’s sensitive curation over two gallery levels, that we see these strands of Lalor’s work thread seamlessly through the whole; what is achieved is a delicate balancing act of ‘loud’ and ‘quiet,’ of expressive and static, of emotive and objective. The work of a lifetime with all its angles.

Assessing five decades of work is beyond the scope of a short article, however some impressions have stayed with me. At his best, I find Brian Lalor ‘sings’ through wood and linocut and fascinates through etching. His dexterity with an etching needle, as seen in his 1980 etching ‘The Fall of Icarus,’ signals a Bruegelian figure able to conjure the extraordinary as a footnote in the everyday. Equally, with a cutting tool in hand, Lalor signals a Munch-like figure, whose sinuous line creates ripples of energy in subjects as varied as Jerusalem, Rome and the Liffey. I would like here to take a closer look at ‘The Fall of Icarus’ etching before turning to the linocuts and woodcuts, and reflecting on his achievements in these mediums.

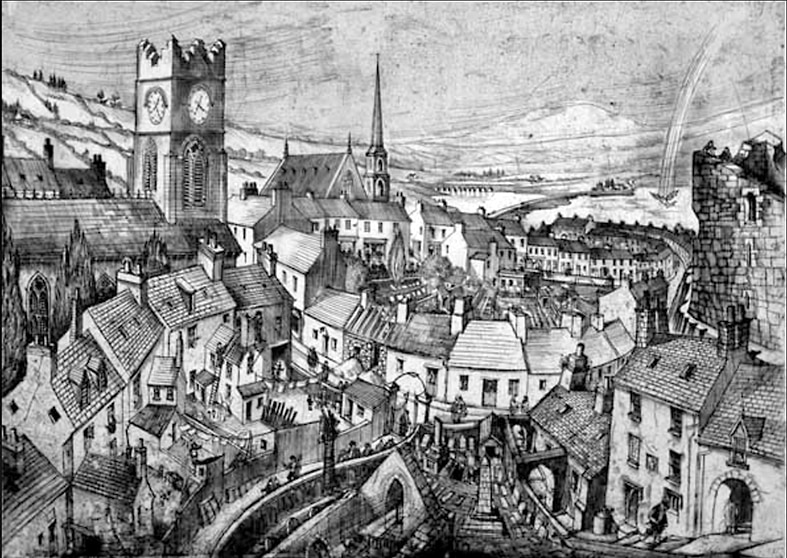

A diminutive Icarus falls, almost as a footnote in the upper right of the composition, towards Ballydehob, the buildings of which voluptuously fill the frame. In the lower right, under an arch, a man is pissing, watched by a cat whilst another man strides up the path unseen, towards him. Elsewhere a woman hangs washing on a line, a man scales a ladder to fix a roof, two women converse outside a doorway, whilst another appears in a window. The scene is both ordinary and mythical, an overview of a small town, captured with Bruegelian humour, intensity and detail.

As an etching, Lalor’s ‘The Fall of Icarus,’ is perhaps, an apotheosis of the artist’s work in the medium, and vies with his large linocuts as one of the best works in his oeuvre. It also shows Lalor engaging with the idea of the ‘world landscape,’ a genre developed in the Netherlands in the 16th century in which an important religious or mythological subject would appear almost incidentally in the background of a scene. The scene itself would often be a composite of idealised mountains, harbours and cities, populated by ordinary people going about their everyday business.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted the very same subject in the 1550s. In the foreground of his ‘Fall of Icarus’ we see a farmer ploughing his field. In the middle distance, before a large ship the legs of a diminutive Icarus flail as he sinks into the sea. Lalor shows, through many pen and ink drawings, such as his Cork City illustrations from 1967-75, and certainly in his etching of ‘The Fall of Icarus,’ a similar sensibility to Bruegel (who so loved to depict the ‘everyman’), though it would be misleading to labour the point. Just as prevalent, after all, are Lalor’s perspectival renderings in aquatint of city and harbour views without a soul (or narrative hook) in sight. The artist–as–architect is never far from the artist–as–myth maker.

Lalor’s work in wood and linocut carries a very different energy to his etchings and pen drawings. It is as if the very nature of the cutting tool sets him free; his delicate, illustrative laces untied, he gives reign to an expressiveness unmatched in his etchings or pen and inks.

In several woodcuts from 1993, titled ‘Oh, look at the snow, they cried, Killiney Hill,’ ‘The Liffey from Poolbeg,’ and ‘Blustery weather at Sea Point, Martello’ we are met with Munch-like compositions and highly energetic, rhythmic cuts, similar in feel to the energetic flight of his larger linocuts. Although they lack the narrative edge of works such as ‘The Fall of Icarus,’ they hardly need it, so joyously do they soar upon the eye. Of the artist’s larger linocuts, ‘Rome from the Piazzale Napoleone’ (1993) is perhaps the most exuberant. The confident, flowing line, the combination of positive and negative spaces, the rippling, yet anchored composition, reverberate in the mind long afterwards. The lack of a narrative hook, here, seems beside the point. The artist is singing and the line itself haunts.

When Lalor’s dynamic sense of line does come together with a narrative, however, he is arguably at his very best. His woodcut illustrations for ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (2012) and ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ by Oscar Wilde (1997) stand out in the retrospective as masterpieces of expressionist woodcut. The flowing, joyful lines of his expansive land and cityscapes are here replaced by something more brutal and direct; the effect is darker and altogether more potent. Vera Ryan, the curator, has intriguingly placed them in the same space as his 1967-1975 pen and ink illustrations for a book of poems by Eileán Ní Chuilleanáin. The drawings depict various streets and their inhabitants in Cork City and prefigure the equally delicate, yet looser handling of his 1980 etching ‘The Fall of Icarus,’ contrasting markedly with the brutal, expressionist woodcuts beside them. The three sets of illustrations concisely reflect, in a small space, the shifting energies in Brian Lalor’s work over the course of his career, from tight and delicate, to expressionist and dynamic.

The Brian Lalor retrospective is an exhibition full of both whispers and crescendos; it is a timely and fitting tribute to an artist and writer whose contribution to the Irish cultural landscape – as an artist, writer, collector, gallery founder and advocate – cannot be overstated. Most importantly it is a lyrical evocation of a life given to print in all its varying forms. Lalor’s lines echo and print themselves upon the mind.

The exhibition is on at Uillin, West Cork Arts Centre, Skibbereen, until October 12. Online gallery:brianlalor.ie