An Taoiseach Micheál Martin delivered a keynote and wide-ranging address at the National Civil War Conference at UCC on June 15. He dealt with several of the atrocities committed during the period including Ballyseedy and the ‘execution’ of prisoners, Dick Barrett, Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellow and Joe McKelvey, who were put to death, without charge or trial, on the orders of the Free State Government.

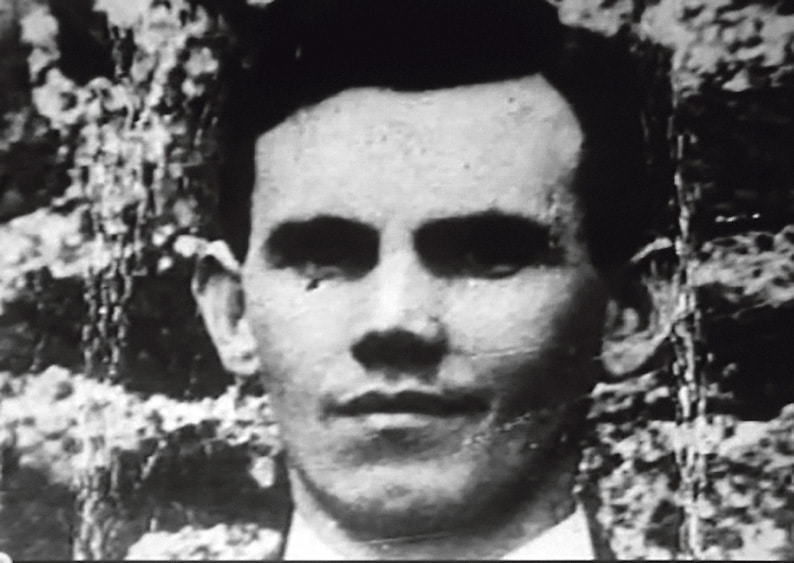

Speaking of that horrific act, An Taoiseach said, “It was manifestly illegal and it damaged the standing and authority of the new state. They had each been in custody for over five months and in the case of Dick Barrett he was executed without trial or court martial as a reprisal for an IRA policy which he was known to have opposed”.

An Taoiseach went on to say that, “we need to find a way of talking about our state’s formation while admitting the radicalising and destructive impact of such actions. But it is also essential to acknowledge the full picture. For example, the murder of Deputy Seán Hales was manifestly wrong and promoted no positive cause – something which Dick Barrett, his old acquaintance from Cork, understood”.

Having recently sought a state apology for the killing of Ballineen man Dick Barrett, at the hands of the first government, members of his Commemoration Committee are very pleased to hear the Taoiseach concede that his death and that of his comrades were manifestly illegal. His thinking on the atrocity is very much in line with that of the Tánaiste, Leo Varadkar, who stated in the Dáil, on November 24, 2011 that, ‘people who were murdered or executed without trial by the Cumann na nGaedheal Government were murdered. It was an atrocity and those people killed without a trial by the first government were murdered. That is my view’.

During his address, An Taoiseach recounted his own family’s involvement in the War of Independence and how as children they learned of the “incredible determination and bravery of our grandparents”. Yet, they weren’t told the stories and events of the Civil War as it was ‘not a time to be celebrated’.

In this the centenary year of that tragic event, discussion, acknowledgement and leadership may help in the healing and reconciliation process.