Perched on the side of hill surrounded by bare rock and overlooking the breathtaking vastness of the Atlantic ocean, Danny and Geraldine Osborne’s home, a small renovated cottage, at one time could only be accessed by walking through the surrounding fields. It was this wildness and raw beauty that first attracted artist Danny Osborne to the Beara peninsula in 1971 and what drew him and his family into a lifelong relationship with another wilderness, the Arctic. Mary O’Brien returns to the place where she first met the artist almost 20 years ago and finds that while the landscape has changed slightly, Danny, now 74, is still fascinated with geology and painting landscapes of ice and snow, travelling regularly between Beara and the Arctic to capture the effects of glacial erratics and the rocks smoothed by the ice. At the other extreme of temperature, Danny is also the first man to ever cast a sculpture from the molten lava of a volcano. One of his best-known pieces of work is the statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square in Dublin.

Born in the South of England, Danny moved to Allihies in 1971 after finishing his training in industrial ceramics at art college. Six years later he borrowed some money, packed some supplies and set off from Allihies on a painting expedition to the Arctic. It was the first of many such journeys and the beginning of a close relationship with the Inuit, formerly known as Eskimos, in the Canadian Arctic.

Over the years Danny and his family have adopted the Arctic as their second home: The Osborne family settled there permanently from 2001 to 2013 – with a brief spell back in Beara in 2004 – after Geraldine, a public health doctor, got a job there as as associate chief medical officer of Nunavut, which was designated an independent territory in Canada’s High Arctic. “It was supposed to only be for a couple of years but we ended up staying,” says Geraldine, who went on to become chief medical officer for the territory, assisting the indigenous population with their transition into the modern world. “There were a lot of challenges, particularly with mental health and outbreaks of TB, but it was also a very exciting time helping people to adapt to this new lifestyle.” During that period, Danny worked with the Inuit community helping them to create some unique large carvings. He was also the sculptor behind a High Arctic Exiles monument and Nunavut land claims monument.

Danny and Geraldine met when he was organising the first ever Irish Arctic expedition in 1981. A medical student from Kildare, Geraldine was a volunteer in the supply warehouse for the expedition. A huge undertaking, the expedition led by Danny and scientist Gerry Wardell, took a year to plan and several tons of food supplies. Danny was doing a study of Irish geese summering in the Arctic and he made a lone six-week ski journey, the longest ever made at the time, with only a dog, quarter wolf, for company. The expedition was filmed in a documentary entitled ‘Beyond the North Wind’.

A few years later Danny and Geraldine got married and started planning a trip of their own. Geraldine didn’t want to go to the Arctic and so they settled on Chile and the Andes to see what is possibly the largest collection of volcanoes in the world. “I wanted to go somewhere hot,” laughs Geraldine. “Danny wanted to see rock.” The couple were also conducting scientific research on red blood cells and filmed a documentary, ‘Halfway to Heaven’. Their eldest daughter Tempy was six-months-old at the time and stayed at home with Geraldine’s mother.

A photo of Danny casting molten lava from a flow in Hawaii

Filming the journey themselves, the couple walked for eight to ten hours every day in the winter, their llamas carrying their cargo including cameras, around ice and lava, during the six month trip through a remote uninhabited part of Chile. Surviving on a diet of dried potato and dried mule, the adventurers made their way up the mountain to a volcano, where Danny spent two nights sleeping and painting.

“I was sleeping right on top of the lip of the volcano so there was an awful lot of noise,” says Danny. “It was like hearing 20 jumbo jets taking off at the same time.”

Geraldine was camping further down and recalls thinking the Llamas were acting very restless. “I did wonder at the time if they knew something I didn’t,” she shares.

About a month after Danny and Geraldine left, the volcano erupted for the first time in 100 years.

And so started Danny’s love affair with volcanoes. He went on to make many trips to erupting volcanoes in Hawaii and Guatemala to catch molten lava flowing from volcanic vents to create sculpture. Using a 20-foot pole, Danny was the first person to ever cast lava directly from a molten flow.

With lava flowing at a temperature of around 1,250 degrees Celsius, the heat on a volcano can get unbearable. “It’s extremely hot especially if there is a a breeze coming towards you across the lava,” says Danny. “And it can be very difficult to drag the mould back out of the lava when it’s solidifying. It’s best to do things very quickly!”

“You’re looking at creation, it’s amazing,” shares Geraldine.

With lava literally flowing around your camp, this is not an expedition for the fainthearted. Danny recalls one time when the couple were camped in a sheltered place at the bottom of a volcano in Guatemala. “We were up on top looking down at the lava flow and I suddenly realised our camp was in this bowl, an old crater, a classic gas trap, which we didn’t realise when we set up tent there. Luckily we were fine,” he shrugs.

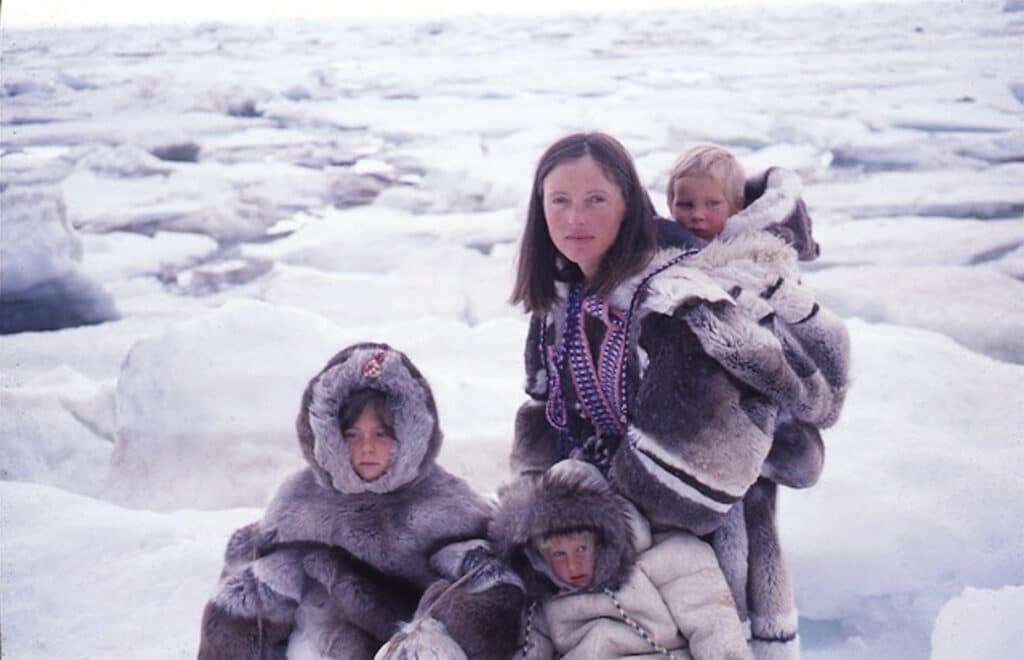

Sharing a spirit for adventure, the husband and wife were both part of a large climbing team from Ireland for the North Peak of Everest expedition in 1987 and, in 1989 the entire family set out on their first trip together to Canada’s most northerly community, Grise Fjord. Like true Osbornes, the children, Tempy (5), Orla (2), and Oisín (1) adapted easily to the different lifestyle, which involved eating raw meat, dressing in caribou skins and coping with minus-40-degree temperatures. “They looked on travelling around in a dog sled and eating seal meat as perfectly normal, because that’s what the Inuit kids did,” says Danny.

“It was one of our favourite trips. The children helped break the ice with the locals and the people were very welcoming to us. They were still hunters and spoke Inuktitut so we got a glimpse of what their traditional culture was like,” shares Danny.

Danny trained a team of dogs over their first winter and the Osborne family wore down-filled clothing to keep warm when they camped on the sea-ice, which stays frozen until the middle or end of June. “You learn to butcher seal meat very quickly for the dogs before your hands freeze,” says Danny.

“We did almost fall through the ice once. The crack was covered with soft snow and we were very tired but luckily when the sled keeled over the handlebar caught on the side.”

“You don’t feel scared at the time,” says Danny, who has fallen through ice on numerous occasions. “It’s afterwards you feel the shock of the situation.

“It’s a very visual and exciting place to be, where you see things found nowhere else in the world.”

Danny spent one month painting a 5ft high iceberg. “The weather changed when I was in the middle of painting it, so I had to leave the painting there. It got covered in snow and was a source of great entertainment to the locals, but because it was oil on canvas there was no damage,” he explains.

From October to February there is complete darkness in the Arctic, making it impossible to paint anything other than the Northern Lights. The days start to get lighter very rapidly and by the end of April there is light 24 hours a day.

“When travelling it meant we could make our days 36-hours-long,” shares Geraldine “which was necessary because between making camp and breaking camp and getting everything ready it doesn’t leave you much time for getting places.”

On one of Danny’s painting trips, an iceberg, which had broken off from the base of a glacier, came crashing up through the 7ft sea-ice, about 30ft away from his tent. “All of a sudden there was this massive explosion and big blocks of sea ice as big as a truck suddenly started flying through the air, right into the tent. It was a close call. I was about 100 yards away before I even looked back. It cracked the ice all around the tent.”

Returning to Beara after a year the family settled back into life in Allihies until their return to the Arctic in 2000 after Geraldine secured a job in Iqaluit on Baffin island. Two of the children, Orla and Oisin completed their high school education there.

Danny explains how the education system in the Arctic is very different from Ireland. “There is no discipline imposed in schools. But that’s part of the cultural make-up of the Inuits. Children are never told what to do and they respond by behaving quite responsibly.”

Today Danny and Geraldine are settled into a quiet life in Beara, interspersed with regular trips back to the Arctic: Danny, who still paints every day, visited last year and they both plan on making the trip there in 2024. The children are following their own paths: Orla is taking some time out from work and planning a sailing trip down to the Caribbean; Oisin, an artist, is currently backpacking around Australia and Tempy is settled in Brussels with three children.

“For me Allihies is definitely home but when we came back the last time it took about two years to figure that out,” says Geraldine.

It was harder for Danny to come back. “The world changed quite a lot while we were away the last time,” he muses.

Danny has been working on some etchings featuring people in the Ukrainian war, which will be shown in an exhibition at the Lavit gallery in Cork. He is also hoping to have a solo show in Dublin later this year; a big collection of his paintings and sculpture from the past few years, it’s one to watch out for.

Top: Meta Incognita, 122cm x 91cm, oil on canvas, 2007.

Bottom: RHA lava installation detail