The DNA of West Cork People

Mark Grace is a genetic genealogist and family historian at Ballynoe House, Ardfield, Co. Cork

Many of us have given or received a DNA testing kit for a birthday or as a Christmas present, but what are they all about? In this new column, I give an easy, step-by-step guide through the basics of all forms of DNA testing for family history. What do your results mean and how can you use them to research your West Cork (or other) heritage?

This time, I’ll go into the three basic forms of DNA testing. There are two detailed types of DNA test that have more specialised use within genealogy and can be used also for detailed historical and anthropological studies. These are naturally more expensive, but something to consider if you are really interested in your genetic roots. Some testing companies provide a basic result as part of their service when doing other tests. YouTube is a reliable source of conference presentations covering all aspects of research into Irish DNA.

Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA)

This is available to men and examines the direct paternal lineage only, i.e., DNA inherited from your father, from his father, and from his father, and so on. In modern times, assuming a legitimate line, these often develop into wider surname studies. Academics are slowly working back through haplogroups (lines of identical genetic inheritance, which include Irish names) connecting historically-documented groups to modern surnames. In any genealogical timeframe, it is true to say (adoption aside) that you know who the mother is but you cannot always be sure who the father is.

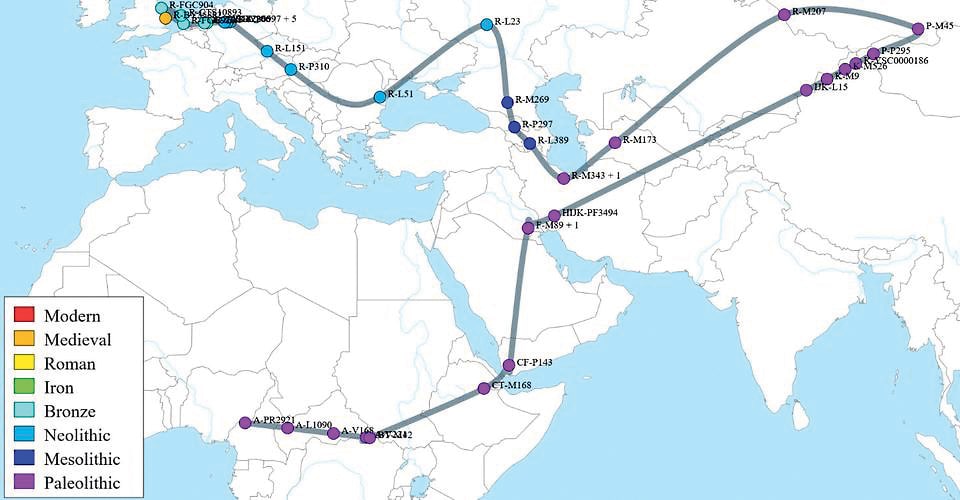

It is also fascinating to see the mutations in your Y-DNA on a map of when and where they occurred. As DNA is copied, errors occur, and on the Y-chromosome one may occur every 110 years or so, so you can go back a long way. It is possible to follow the migration of your ancestors out of Africa.

My most ancient paternity started 240,000 years ago in an area of present-day eastern Nigeria. Their descendants migrated and are mapped as having crossed the Red Sea into Arabia about 87,000 years ago. During the Palaeolithic, they were following migrating animals, including mammoths, into the Asia steppe, before retreating ahead of the ice age to ‘overwinter’ in the Black Sea area for the Mesolithic period. My ancestors were part of the first hunter-gatherers to colonise a post-glacial Europe with my haplotype arriving in the British Isles in the Bronze Age or with the Anglo Saxons.

The genetic path to Ireland for two of the great family names of West Cork, SULLIVAN and DONOVAN, are very different based on their Y-DNA story. Over 700 men (including two Lowneys (aka Sullivan Laune) a common name on Beara) have participated in a Sullivan surname study. Their haplogroup is mainly type ‘I’, indicating a Scandinavian or Norman origin. Normans were Viking settlers in Northern France, which is why the haplogroup is the same. For more information on this study, see familytreedna.com. If you compare their results with more than 100 men participating in the Donovan clan study – (familytreedna.com), their haplogroup is mainly type ‘R’, the same as mine; part of the original hunter-gatherers who colonised Europe and probably settled in Ireland a long time before the Sullivan’s ancestors arrived! In terms of ethnicity, does this make the Sullivans less Irish than the Donovans? I will be discussing ‘ethnicity’ next time.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

This test looks at the direct maternal lineage, i.e., inherited from your mother from her mother, and her mother, and so on. as mitochondria are only inherited from your mother. In the earliest times, mitochondria used to be separate lifeforms, which moved inside early cells to form a symbiotic relationship with the host. They became the cell’s power stations, enabling higher life forms to develop.

As with Y-DNA testing, you will receive a haplogroup and can similarly follow the history of mutations and the migration of your direct maternal line out of the East African Rift Valley back 160,000 years from what is known as the Mitochondrial Eve. This is a concept or group of early humans, rather than a ‘who’.

My wife’s mtDNA haplogroup is ‘H’ (aka Helena), which passed through her most distant maternal line in the HARROLD family from Murragh (Ballineen) from her unknown mother. In the post-glacial period, ‘H’ came via the Caucasus 15,000 years ago. In contrast, my haplogroup of ‘T’ (aka Tara) originated in the Levant 20,000 year ago. mtDNA was used to help prove the remains of Richard III of England.

Autosomal DNA (atDNA)

This is the usual DNA test sold and is an affordable present to family or oneself. As shown on the chart, the size of atDNA databases has grown enormously in recent years. AncestryDNA (for genealogy) is being closely tracked by 23andMe whose primary focus is health traits, even though their data can be used for genealogy. MyHeritage is in third place, growing through their own testing kits as well as accepting uploads of raw DNA files from other testing companies, which they take for free.

This type of DNA is inherited through your autosomal chromosomes (autosomes), a random 50 per cent mix received from both your parents; theirs being a 50 per cent random mix from their parents, likewise. Over the generations, the older signatures get diluted and become harder to find. Excluding the sex chromosomes X and Y, humans have 22 pairs of autosomes.

This test finds segments of DNA that have been passed down from relatives on every branch of a family tree, revealing close relationships such as parents/siblings/aunts/uncles/first cousins and so on, with a high degree of accuracy. However, the test has natural limits due to the randomness of inheritance. For example, you may not inherit DNA from all your two times great grandparents. A theoretical limit for this type of testing is about eight generations. My research involving families outside of Ireland has identified genetic matches back to the late 1600s and eighth cousins. If you are lucky, segments survive the generations alike this and can be recognisable as part of certain family lines or from certain geographical areas.

Of course, as ‘DNA never lies’ you may find that your DNA signature does not match part of that carefully researched family tree built over many years. This is where genetic genealogy gets even more interesting and you should be prepared for surprises!

Next month, I will be discussing the meaning of your ethnicity results. What does ethnicity really mean in terms of your DNA and how reliable are the results?

For any questions that can be answered as part of future columns (genealogy@creativegraces.net) or follow the Cork DNA projects based on my wife’s DNA and her genetic cousins, on Facebook ‘My Irish Genealogy and DNA’.