While today we are more inclined to see life as a linear progression from our physical birth through to our death, a beginning and an ending , Eugene Daly says the ancient Irish saw life as a recurring cyclical process of birth, life, death and regeneration.

In the midst of life we are in death – both are part of the ever-turning wheel. The death aspect surfaces whenever a change occurs. So, for example, the end of a relationship, redundancy, children leaving home, the death of a parent, loss and every goodbye are all mini-deaths that exist as part of the eternal cycle.

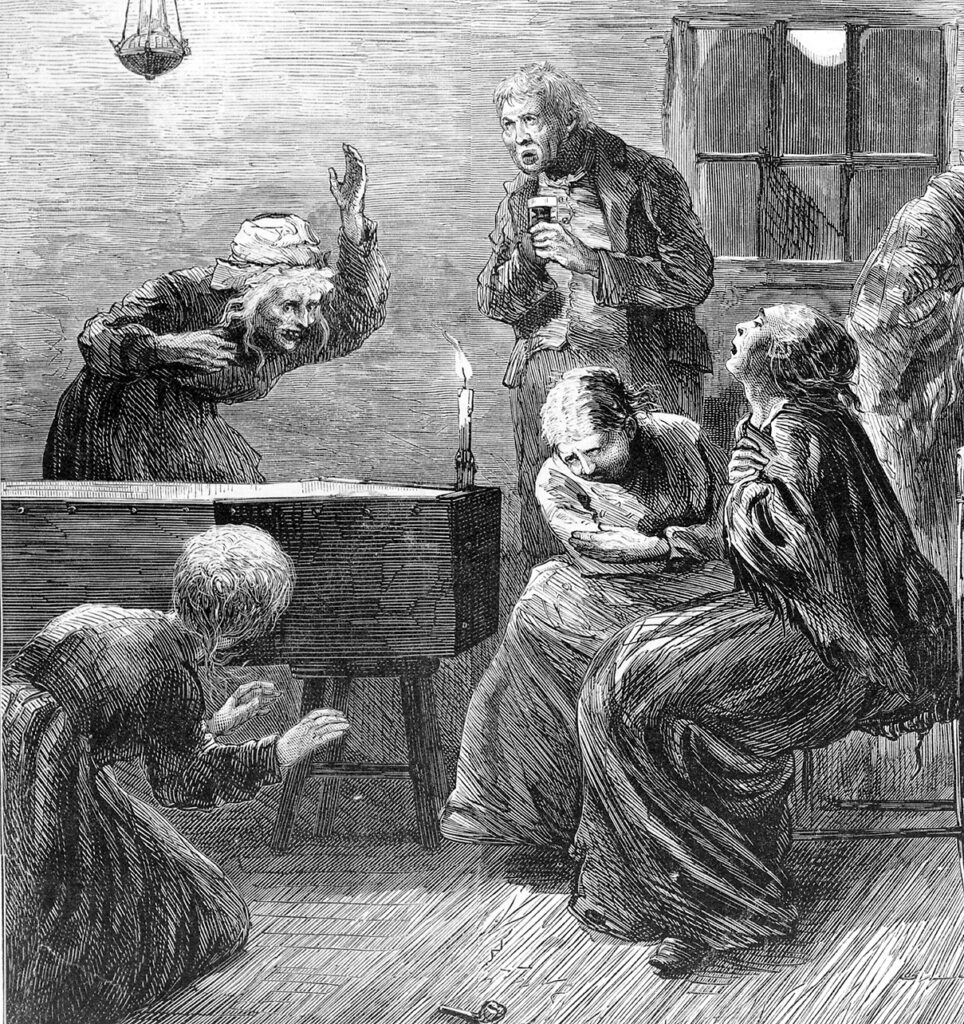

The ancient custom of ‘waking’ the dead at home still survives in parts of Ireland; at one time it was always done. When a family member died, someone went immediately for provisions of food and drink for the wake. The corpse was usually laid out by neighbouring women who washed the body, put a habit on it, and prepared the bed on which the corpse was placed. A crucifix was laid on the breast and rosary beads entwined in the fingers. Candles were lit on a table near the remains. The immediate relatives then approached the corpse and expressed their grief in either muffled sobs or loud wailing or keening (keen comes from the Irish word ‘caoin’, to cry). The practice of women keening the departed was common in our grandparents’ time. It was practiced on Cape Clear and Heir Island up to the mid twentieth century.

When a person died the clock in the house was stopped immediately. All work ceased in the townland when the news spread. The neighbours came in to express their sympathy (‘I’m sorry for your trouble’ is often the usual expression), prayed for the dead person and then retreated to another room. Custom demanded that the corpse must not be left unattended for the duration of the wake before being brought to the church on the evening before the burial. The wake-house was visited during the day mainly by elderly people, and at night all the other neighbours came to pay their respects. All were given food and drink, and in earlier times, snuff or tobacco. In olden times large numbers of new clay pipes already filled with tobacco were put in charge of a neighbour, whose task it was to see that every man who came got a pipe, and every man had to light up and take a few puffs whether he was a smoker or not. Any woman who wished to smoke also got a pipe. Most of the ladies, however, contented themselves with pinches of snuff.

The Rosary was recited at least twice during the night, around midnight and again towards morning. Most of the neighbours would leave after the midnight Rosary, but relatives and close friends kept an all-night vigil.

‘Waking’ the dead suggests that death was an integral part of life and should be acknowledged publicly as a transitional experience to be shared with family and friends. References to death are ubiquitous in Irish literature. In Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’, Leopold Bloom proclaimed that ‘the Irishman’s home is his coffin’. Many Irish autobiographies begin with accounts of death or dying. For example, the first words of Peig Sayers life story ‘Peig’, reveal that she is old and poised between two worlds: ‘Seanbhean is ea mise anois a bhfuil cos léi san uaigh is an chos eile ar a bruach’. (I am an old woman now with one foot in the grave, and the other foot on its edge’). Hugh Leonard revealed amusingly in ‘Home before Dark’ that his grandmother had made ‘dying her life’s work’.

Several proverbs emphasise the inevitability of death. Among them we find the following: ‘Nil luibh ná leigheas in aghaidh an bháis’ (There is neither herb nor cure against death). Some proverbs reveal a combination of humour and fatalism in the face of one’s mortality, for example, ‘Lia gach boicht bás’ (The cure for all poverty is death). The term ‘fatalism’ involves an expectation that one’s life is determined largely by forces outside one’s control, such as luck, fate or the influence of powerful other people. Irish folklore is full of references to fatalism.

The brevity of life is emphasised by proverbs, which contrast its transience with the more enduring aspects of natural phenomena. For example: ‘Maireann an chraobh ar an bhfál ach ní mhaireann an láimh do chuir’ (The branch lives on the hedge but the hand that planted it is dead). Another example of this idea is the saying: ‘Is beag an rud is buaine ná an duine’ (the smallest of things outlives the human being).

Some proverbs explore the way our perspective on death may be influenced by our age and our emotions. Older people naturally tend to think more about their mortality than do young people. ‘Bíonn an bás ar aghaidh an tseanduine agus ar chúl an duine óig’ (death is in front of the old person and behind the young person).