“From about the middle of the 18th century it began to be realized that you could learn from a dead body; and that’s when some families were starting to be persuaded that they should allow post mortems.”

– Wendy Moore

In the 18th and 19th centuries medical and surgical students needed bodies to dissect. The rise in surgery’s popularity meant that there was a greater demand for bodies to work on and study. However, at the time, it was only legal to dissect the body of a convicted murderer. The ‘Murder Act’ of 1752 decreed that the bodies of all murderers be dissected as an additional punishment for the crimes they committed. Most of the bodies used for dissection were taken from Tyburn in London. Tyburn was the site of execution since the 12th century. Locals called the permanent scaffold there, ‘The Deadly Nevergreen’, as it was the tree that bore fruit all year long. Between 1169, which was the year the first recorded hanging took place, and 1783, when the executions were moved to Newgate prison, an estimated 60,000 people died at Tyburn.

When the ‘Murder Act’ was passed Tyburn became a battleground where people fought for the bodies of the corpses. Fights took place between surgeons who needed to procure bodies for dissection and the victims’ families who wanted to keep and bury the bodies of loved ones. In 1740 Samuel Richardson wrote of one battle he witnessed;

“As soon as the poor creatures were half dead, I was much surprised before such a number of peace officers to see the populace fall to hauling and pulling the carcasses with so much earnestness as to occasion several warring encounters and broken heads. These are the friends of the persons executed and some persons sent by private surgeons to obtain bodies for dissection. The contests between these were fierce and bloody and frightful to look at.”

The public’s desire to see justice did not necessarily include a desire to see the criminal body dissected. It was a common belief at the time that after death the body should remain intact. Fears about what happened to the body after death were extremely prominent in the 18th and 19th centuries. The idea of organs or body parts being removed, led to the possibility of having to live without them in the afterlife and this was terribly disconcerting for people and cause genuine concern. Before the day of execution, the condemned went to great lengths to protect their bodies from being removed to the ‘dead house’, which was the surgeon’s dissection table. They would write letters from jail and appeal to their families, friends, husbands and wives to organize a group of people of some form of security to prevent their body being taken and anatomised by surgeons.

Martin Grey begged his uncle to come and be present at his execution in 1721 to prevent his body from ‘being cut and torn and mangled after death’. Children were also hanged for murder and on July 29, 1831, John Amy Birdbell, age 14, was convicted of robbing a young boy of his money and murdering him. At his trial, it is recorded that John showed no emotion upon being sentenced to death, however, he cried when he was informed, his body after execution, would be given to a surgeon for dissection. It is written in historical evidence that, as he made his way to the gallows, he turned to the Constable and asked “He, the murdered child, is better off than I am now, do you not think so Sir?’ After his execution, his body was removed for dissection.

Surgery in the 18th and 19th centuries was an incredibly rudimentary practice. This was prior to the invention of antiseptic, anaesthesia or antibiotics. Germ theory had not been discovered yet, the job itself was filthy; the dissection rooms were known as ‘death houses’ and were filthy.

In 1793, James Williams, a 16-year-old student, described his living quarters next to John Hunter’s anatomy schools in a letter to his sister:

“My room has two beds in it and in point of situation is not the most pleasant in the world. The dissecting room with half a dozen dead bodies in it is immediately above and that in which Mr. Hunter makes preparations is the next adjoining to it, so you may conceive it to be a little perfumed. There is a dead carcass just at this moment rumbling up the stairs and the resurrection men swearing most terribly. I am informed this will be the case most mornings at about four o’clock throughout the winter.”

Dissecting was considered a winter sport, and the bodies, if they had not been operated on the day of the corpse’s execution, were often already at an advanced state of decomposition. A body begins to decompose immediately after death and cells and tissue begin to break down in a process known as autolysis. During this time oxygen present in the body begins to deplete creating an ideal environment for the proliferation of anaerobic organisms in the gut and respiratory organs. Eventually the body begins to bloat and can cause ruptures in the skin as gases escape. As time passes the body begins to digest itself and organs become liquefied. The bodies would have been swollen, leaking, and the smell of rotting flesh would have permeated the surgical rooms. Insects, rats and mice would have been present in the dissection rooms; they are known to have been feeding on the cadavers. There are recorded journal entries of surgeons feeding the rats and mice pieces of the dead to keep them off the tables.

Because surgeons were not aware of germs yet and had no understanding of surgical hygiene, they didn’t wear gloves and often operated on cadavers in their own casual, everyday clothes. This meant the blood and infectious diseases, as well as germs that fester in a decomposing body, would have been all over their clothing, which wasn’t washed, and which they wore home where they prepared meals and went about their daily lives!

The death rate of surgeons was extremely high due to infection. There are many recorded cases of surgeons dying within 48 hours of cutting their finger during a dissection, as the wound would be infected almost immediately. Antibiotics had not been discovered yet. So death was almost guaranteed. In 1788 a young medical student cut his finger while dissecting the dead body of a child. A few hours later he began suffering from headaches and later began to haemorrhage. Within 24 hours he was dead. His name was Charles Darwin: The uncle of the now famous evolutionary biologist of the same name. With the high death rate and the need for improvement in surgeon’s skills, as well as surgical practices, the demand for bodies increased. By the 19th century demand for bodies was extraordinarily high. Acquiring bodies at executions and the difficulties in obtaining the bodies became more and more difficult, as chaos ensued, with people fighting for the corpses at every event.

This led to a huge demand for dead bodies. With that came the invention of bodysnatching. Grave Robbers or ‘Resurrection Men’, as they became known, would monitor funerals that were taking place all over Britain. This practice was also used in Europe and America. They would wait for the funeral to take place, make a note of the burial site, and return under the cover of darkness to remove the bodies from the coffin and take it to the ‘dead house’ to sell to the awaiting surgeon. Unusually Resurrection Men would strip the body naked because it was illegal to steal possessions from the corpse but not the body itself, as there was no concept of the body being property. They would throw the clothes and jewellery back into the grave after removing the corpse. The process of bodysnatching was highly lucrative and, because of its profitability, it became widespread all over Britain. Resurrection Men could charge £10.50 per corpse. By comparison, the weekly wage of a master tailor or a carpenter in the same period was £1.50; the body trade took off and the need to protect graves from body snatchers became a necessity for those who could afford it. The ‘cemetery gun’ was invented to prevent the theft of bodies.

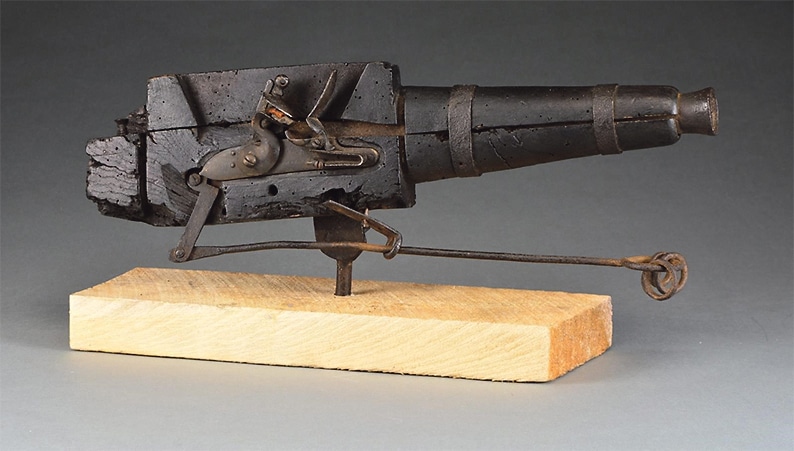

To combat the problem, creative cemetery workers fashioned what is known as the first ‘cemetery gun’, a flintlock pistol, mounted on a rotating base and stand, which would allow it to swing freely. Set near the foot of the grave and pointing towards the head, the gun would have been triggered by a series of three or four tripwires extending in an arc pattern and encompassing the fresh grave. Unsuspecting thieves, working under cover of darkness, would presumably not notice the tripwires, stumble upon them, and meet their own demise, or at least get a dose of lead. Though it is not clearly documented whether the guns actually worked, it would be safe to expect they were at least a great deterrent if not a truly fatal tool of defense.

There are accounts from around the US of these guns being available for either rent or purchase by families who wished to protect their recently-deceased loved ones. Those who could not afford the gun rental were at the mercy of the body snatchers. Resurrection men evolved to meet this challenge. Some would send women posing as widows, carrying children and dressed in black, to case the gravesites during the day and report the locations of cemetery guns and other defenses. Cemetery keepers, in turn, learned to wait to set the guns up after dark, thereby preserving the element of surprise. One of the only known surviving examples of cemetery guns is on display at The Museum of Mourning Art at the Arlington Cemetery of Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. Museum curators date the gun to 1710, making it one of the earliest models of cemetery guns. Part of its original rotating pedestal and three rings for tripwire attachment are visible in the photo

The ‘Anatomy Act’ of 1832 was introduced in Britain, which meant the bodies of any unclaimed poor people could be used for dissection. It was thought that this would reduce the trade of bodysnatching. It did. The late 1860s marked not only the end of the Civil War, but also the heyday of body snatching. By the 1870s, cemetery gun technology advanced into what became known as ‘Coffin Torpedoes’. These were essentially very short-barrelled shotguns mounted inside the coffin lid and triggered by the raising of the lid. Success must have been limited because they quickly gave rise to ‘Grave Torpedoes’, which were not really firearms at all, but rather small explosives packed with black powder and ignited by percussion caps. The torpedoes would rest either atop or just inside the coffin lid. When disturbed, the explosive would detonate into the face of unsuspecting diggers.

The ‘Anatomy Act’ of 1832 was unsuccessful in its attempt to stifle the rise of body snatching, however, the aforementioned methods were a successful deterrent and the trade rapidly declined. While grave robbery of valuables still occurs on occasion today, body snatching has faded into the annals of history. Undoubtedly, there are some coffin torpedoes still locked and loaded in many undisturbed 18th and 19th centuries graves now in the 21st century, although, with the passing of time, they are unlikely to detonate.