‘This Is The Mizen’ presents a rigorous and wide-ranging investigation into the history and landscape of the Mizen Peninsula in West Cork. Drawing on extensive research and a journalist’s eye for detail, John D’Alton, a long-time Mizen resident, brings clarity to a region often obscured by myth, assumption, and romanticisation.

Rather than relying on local lore or well-worn narratives, D’Alton interrogates the available evidence – archaeological, geological, historical and anecdotal – to construct a grounded and nuanced account of The Mizen’s past. The result is a study that not only corrects common misconceptions but also uncovers overlooked aspects of the region’s cultural and physical history, from prehistoric structures and medieval trade to famine-era injustices and modern misinterpretations.D’Alton, also a published photographer, has filled the book with beautiful and unique views of The Mizen. ‘This Is The Mizen’ is a comprehensive and accessible exploration of a rugged landscape often seen but never before examined in depth.

A must-have history and guide for residents and visitors alike, it is available in selected bookshops and online at buythebook.ie. Softcover €30, hardback €60.

An extract (condensed) from the book telling the story of how Europe got to learn of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, featuring Crookhaven, County Cork.

When an attempt was made on Donald Trump’s life during the 2024 US election the news went around the world in seconds. This is the world we live in. Consequently it is impossible today to believe that the news of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865 took almost twelve days to reach the first place in Europe to learn of it: tiny Crookhaven in far West Cork.

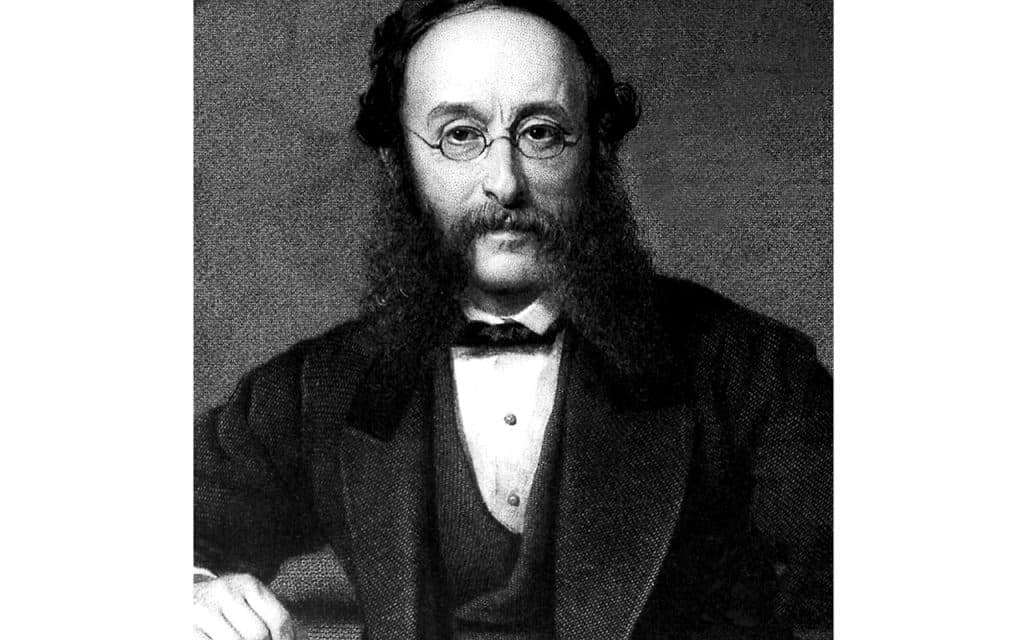

Why Crookhaven? Julius Reuter, of the eponymous news agency, by 1863, was in a fight for survival with his customers to be the first with the news from the United States of America. He had a contract with the Associated Press (AP) in New York for the exchange of news. The American news was dropped off from Cunard liners at Roche’s Point, Cork, conveyed to Reuter’s office there and telegraphed to his subscribers throughout the United Kingdom. His news supply chain began in New York where the AP put newspapers and other dispatches onto Cunard ships departing for Southampton or Liverpool. Anything newsworthy that occurred during the following four days was telegraphed to Cape Race on the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland, and transferred to the trans-Atlantic liners which passed close by. This was the fastest method to get the latest news from America after the failure of the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable in 1858, the Atlantic Ocean having proved a more formidable obstacle to the spread of the telegraph than the English Channel and the Irish Sea.

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 threw the cotton industry in England into turmoil. Before the war, America’s southern slave states were the source of eighty per-cent of cotton used by the British textile industry. By August 1861 that figure had dropped to zero. As one-sixth of the English population was dependant on cotton for its livelihood, this caused widespread unemployment and enormous hardship, particularly in Lancashire. It also increased the British demand for up-to-the minute news from America to fever pitch.

It was a British inventor, Frederic Gisborne, who first identified the potential of Newfoundland as a suitable location for the exchange of news between the Old World and the New. Westbound news, deposited at Newfoundland, could be forwarded telegraphically to New York. Likewise, eastbound news, having left New York could be updated at Newfoundland. Newspapers and news-agencies would pay handsomely for this four-day advantage. When Gisborne realised that ships were not going to put into port he came up with a novel solution: intercept them at sea. He proposed that the telegrams be put in a barrel for the ship’s crew to throw overboard as they passed Cape Race eastward. Once the barrel was retrieved, its contents would be transmitted to New York. Although not implemented by Gisborne, this transfer method became operational when the AP became aware of the telegraph at Cape Race, and in 1859 stationed a ‘news boat’ – a small steamer – there and a boatman to operate it, one John Murphy. Updates to news already on the ship, were telegraphed to Cape Race, placed in a watertight metal container (much like a marker buoy) and then conveyed by the ‘news boat’ out to sea. According to a Reuter employee in Crookhaven, the watertight containers were about two feet six inches in height, conical in shape and ballasted with lead. Reuter contracted with the shipping companies, principally, Cunard, for the transport of the canisters between Cape Race and Cork. The canister arrangement suited the shipping lines who were on tight schedules: the fees were welcome; the ships did not have to put in to a port to collect the telegraphed dispatches any more; they didn’t even have to slow down as they collected and dropped off the news. From 1859, “Via Cape Race” began appearing in the headings of news stories in the Irish, English, and American newspapers.

Reuter’s business model was based on being first with news, which he sold primarily to the mercantile and banking communities. The invention and widespread adoption of the electric telegraph had created a new industry, the news agency, and Reuter’s, established in London, was one of the first. The scramble at Roche’s point presented his business with the greatest challenge yet encountered. With the war raging, and the outcome far from certain, Roche’s Point was no longer feasible as a telegraph terminus for Reuter.

The rapidly expanding telegraph industry in the UK was first regulated by the 1863 Telegraph Act, which allowed any incorporated company to construct telegraph circuits “…under any Street or public Road and over, along, or across any Street or public Road…”. For Reuter the timing was perfect. If he was to be first with the news he would have to intercept the liners further west, as close to the shipping lane as possible. He commissioned the Siemens brothers of London to construct a private telegraph line from South Mall, Cork to Crookhaven, which was operational by December, 1863 where he established an office, stationed a small steamer and employed four men. His staff used the Brow Head Napoleonic-era signal tower to sight liners which were signalled using rockets. He would have to intercept the liners south of the Fastnet but he would now have a three to five hour advantage over his customers and competitors. Once again he would be first with the news.

Good Friday, April 14, 1865 had all the signs of being a slow news night for New York’s journalists until the news that President Abraham Lincoln had been shot in Washington arrived at AP’s New York office at 11pm. The brief message read: ‘President Lincoln Shot.’

Pandemonium ensued. The scramble was on to find the next, fastest available steamer heading east which, it transpired, wouldn’t leave New York until 5pm the following day. However, further east, the Nova Scotian was preparing to depart from Portland, Maine, at noon on the 15th, five hours earlier and one day closer to Ireland. The AP had a private telegraph line to Portland and immediately telegraphed the news about Lincoln to be put aboard the Nova Scotian which would drop off the news at Greencastle, County Donegal.

Meanwhile, across the river in New Jersey, at midnight on Friday, April 14, an hour after the news of the shooting had reached the AP’s office, the Teutonia had cast off from Hoboken dock bound for Hamburg via Southampton. Reuter’s representative in New York, James Heckscher, one of his most trusted journalists, acting independently of AP, chartered a fast tug to chase down the Teutonia as she steamed out of New York harbour. Against the odds, the tug caught up with the Teutonia and Heckscher threw aboard his news that Lincoln had been shot (not killed, the president was still alive by the time Heckscher caught up with the Teutonia).

The terrible and important news that Lincoln had died from his wound Saturday morning at 7:22am, was in time to be telegraphed to Portland. The headline now changed from: President Shot to: President Assassinated.

The Teutonia was the first of the two ships to make landfall when she appeared off the Fastnet eleven-and-a-half days later at 8am, Wednesday, April 26. Her news was transferred to Reuter’s steamer and telegraphed to London from his Crookhaven office. The Nova Scotian, delayed by fog, but because she had departed after the Teutonia, carried the critical news that Lincoln was dead, which was conveyed ashore to Greencastle at 9:45am and telegraphed to London.

Reuter simultaneously distributed the first news dispatch to his business clients. This subsequently leaked to the wider public from a client, Peabody & Company, an American bank. This initially led to the news being thought a hoax perpetrated by market speculators. The arrival, two hours later, of the news that Lincoln had expired, carried by the Nova Scotian, as well as an official report from the American Legation, confirmed the accuracy of the dispatch telegraphed via the Teutonia from Crookhaven.

As for Heckscher: his valiant effort to provide Reuter with a news-scoop lost all significance once the Nova Scotian made landfall: President Lincoln had not only been shot, he had been shot dead.