Later this Spring, American archaeologist, anthropologist and chef Dr Bill Schindler will teach an online course at University College Cork focused on food heritage and sustainable enterprise. A leading voice in reconnecting modern eating with ancient food traditions, during the pilot programme, Dr Schindler will introduce food cultures from many parts of the world, including Ireland, exploring how traditional and indigenous foodways can be revitalised and reimagined as drivers of sustainable, ethical, and economically viable food enterprises. He chats to Mary O’Brien about his work and why we need to look to the past to reconnect with food for the sake of our health.

While his academic background is in archaeology and anthropology – he holds a PhD in archaeology and has taught at university level for over two decades – it was Dr Schindler’s interest in food, diet and subsequently health that prompted his research into primitive technology and experimental archaeology, relating to how food is actually made.

“Almost every prehistoric technology for three and a half million years had something to do with food, either allowing us to get food, process food, store food, share food or redistribute food,” he says.

Dr Schindler is convinced that using technologies to transform a raw material into something that’s safe and nourishing for our bodies is literally what helped make us human.

It was this realisation that directed his research into ancestral and traditional diets – a journey that transformed both his and his family’s relationship with food.

While filming ‘The Great Human Race’ for National Geographic, Dr Schindler lived for periods using prehistoric technologies, sourcing and preparing food as early humans might have done.

“I realised that there’s so much incredible traditional knowledge still today that can really help transform and inform our modern approaches to food and they’re disappearing very quickly,” he shares.

This life-changing experience reshaped the direction of his work. Taking his family with him, Dr Schindler travels around the world, living with indigenous and traditional groups and learning about their food traditions.

From being taught how to make mursik (ash yogurt) – a fermented milk product – in Western Kenya to getting instruction in how to harvest and prepare insects for a meal in Thailand, Dr Schindler began documenting this knowledge to redefine how we connect with food.

“We are incredibly disconnected. Our food chains have never been longer than they are before,” he explains. By removing some of those links and improving our diet, Dr Schindler believes that we can reclaim our health.

Ireland entered this chapter of Dr. Schindler’s life during a sabbatical year spent living at Airfield Estate, teaching at University College Dublin, and conducting global research – a period during which he also wrote his book ‘Eat Like a Human’. He describes his time in Ireland as transformative, shaped in part by his work with experimental archaeologist Aidan O’Sullivan and the Centre for Experimental Archaeology and Material Culture. Equally influential was his time with Jason O’Brien, founder of Odaios Foods, whose deep interest in hunter-gatherer societies helped inform the creation of a luxury food business rooted in ancient grains and high-quality ingredients.

“I fell in love with Ireland and its food traditions,” he shares. “When you start looking closely,” he adds, “you see that Irish food traditions were incredibly informed.”

Oats are one of the clearest examples. For generations, oats in Ireland were soaked overnight before cooking. This practice reduces phytic acid and other naturally occurring compounds that interfere with mineral absorption. It also makes oats easier to digest.

“Even going back a very short time in Ireland,” Schindler notes, “oats were always soaked. That wasn’t a preference – it was just how you prepared them.”

The widespread use of instant oats, eaten without soaking, is a modern departure from that knowledge. It reflects a broader shift away from process – the steps that once made food work properly in the body.

Butter tells a similar story. Ireland has one of the oldest dairying traditions in the world and there is a good chance butter originated in Ireland possibly as long ago as 6,000 years. For almost all of that time, butter was fermented.

That fermentation process produces vitamin K2, a nutrient essential for bone health and for directing calcium to where it belongs in the body. It also plays a role in how the body uses vitamin D. In a northern climate with limited sunlight, this mattered.

In other words, the diet worked. So it endured.

Milk reflects the same long familiarity. Ireland has one of the highest rates of lactase persistence in the world – the ability to digest milk into adulthood – a genetic adaptation linked to thousands of years of reliance on dairy.

“Traditional cultures,” he explains, “developed methods to make milk more digestible by replicating outside the body what infants naturally do inside it. What we used to do in our stomachs, we now do in a fermentation tank when we culture dairy into yogurt, kefir, butter, and cheese.” Just as cows rely on fermentation in the rumen to break down grasses and birds effectively pre-ferment grains before digesting them, humans learned to ferment sauerkraut and make sourdough bread.

Even the potato, often treated as the simplest of foods today, was handled with care in the past. Potatoes contain natural toxins, particularly concentrated in the skin, and any potato showing green indicates wider toxicity.

“That green isn’t the toxin,” Dr Schindler explains. “It’s a warning.”

Peeling potatoes and discarding damaged ones was once routine. It was not excessive caution, but learned behaviour.

Dr Schindler doesn’t suggest that traditional diets were perfect. Rather he explains how in the past there was a deep understanding of how to make limited food sustain people.

Modern food systems, he believes, have loosened that connection. Ingredients arrive quickly, often eaten out of season, with little sense of where they came from or how they were once prepared.

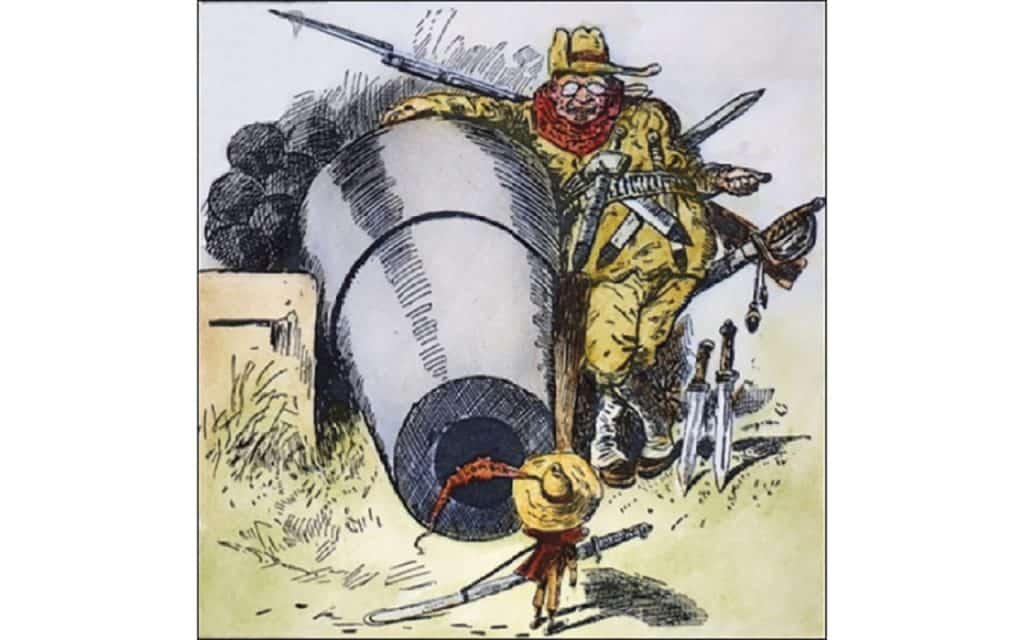

He points to maize as an example of what happens when food travels without knowledge of its processing methods. In the Americas, corn was traditionally treated through nixtamalization, a process that unlocks nutrients such as niacin and prevents deficiency

disease. When corn travelled without that knowledge, a disease called pellagra followed. This disease was seen in Ireland after the Famine when the country relied on corn supplied from the United States as a relief ration.

Foods today promoted as ‘superfoods’ would once have been eaten sparingly and seasonally.

Spinach is one example. It is rich in oxalates, natural compounds that in large amounts can contribute to kidney stones and joint inflammation. Traditionally spinach would have appeared for a few short weeks in spring. Today it sits on supermarket shelves all year, often eaten daily in smoothies and salads.

“I’m not saying don’t eat spinach. Just look at how often you eat it,” advises Dr Schindler.

Almonds are a similar story. Harvesting almonds by hand limited how many a person could consume. Modern almond flour, almond milk and snack packs deliver quantities never previously encountered. “For people sensitive to oxalates, like me, that can cause real problems,” he says.

Dr Schindler believes that modern diets have drifted away from the understanding of what makes food nourishing, with speed and convenience replacing proper process.

While he is not calling for grand changes out of reach to busy families, he suggests small acts like soaking grains, choosing real butter and buying food closer to its source.

“You don’t need to change your whole life,” he says. “You just need to start noticing food again.”

Speaking about the course, Dr Schindler said: “In a world dominated by ultra-processed convenience, the most innovative food solutions might come from the oldest diets. This course is about bringing those ancient lessons into modern kitchens, farms, and markets in ways that respect culture, support sustainability, and create real economic opportunities.”

‘Food Heritage in Action: Turning Tradition into Sustainable Enterprise’ runs for 10 weeks, commencing April 1 2026, and is open to domestic and international participants with full details available at: www.ucc.ie/en/ace/food-heritage/.