At the start of a sultry August the West Cork arts scene is brimming with life. Cnoc Bui, in Union Hall, is once more hosting West Cork Creates, Working Artist Studios, in Ballydehob, boasts a fabulous members exhibition, and the Blue House gallery, in Schull, is presenting a diverse show of gallery artists’ work. Meanwhile Uillin, in Skibbereen, is showcasing a selection of work from the Crawford Gallery, titled Grá, whilst Gallery Asna, in Clonakilty, is once again hosting Cork Potters. Painting, ceramics, sculpture, printmaking, photography; it’s all in the mix, and a proliferation of group shows means that more artists are represented across the region than at any other time of year.

August is, thus, a great time for visiting galleries. It is, however, perhaps not the best time for producing lithographs. Litho what? Most people will be familiar with offset printing. Before the digital age, this was (and largely still is) the mainstay of the publishing industry, the paper you are reading being a classic product of this process. In a nutshell, offset printing is enabled through photo-plate lithography, which in turn is derived from the principles of stone lithography. And stone lithography is what I wish to discuss, for August is also craft month, and it’s time to get technical.

Firstly, a disclaimer; stone lithography is a dark art. Truly. Trying to explain it to the uninitiated (99.9 percent of people) is like trying to explain to a Sami person, in the northern tundra, how a caterpillar turns into a butterfly. We can describe some things, of course; the before and after. But what happens within the cocoon leaves most of us speechless. So, deep breath, and here goes.

To begin with, as the name suggests, one draws on a slab of graded, level limestone. This is very primal, stone age even. And so far you’re with me, excellent.

Then, and here’s where things get wooly, the lithographer-mage treats the stone with varying mixes of gum arabic and nitric acid. Some words may be said, some prayers, even. The stone is left alone for a while to absorb both prayers and chemicals. When the lithographer-mage returns, perhaps a day later, they may decide to ‘proof’ the stone. This is a way of checking that the treatment (and the prayers) have worked.

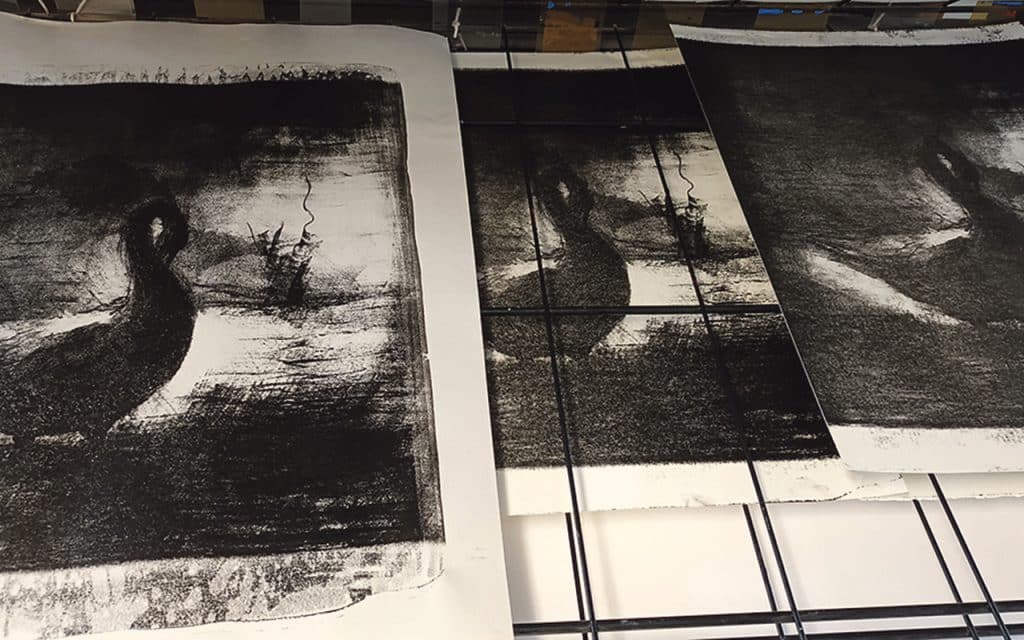

Firstly the drawing is removed from the stone with white spirits. Yes, that’s right, sayonara stone age drawing! If all has gone well, however, an x-ray-like image remains ‘lit’ in the stone, as if the spirit of the drawing remained whilst its body departed. Following this cathartic moment, a greasy substance called asphaltum is rubbed into the ghost-image, after which the previously applied layers of gum arabic are washed away with a sponge.

Now for the ink. The lithographer rolls up black proofing ink, dampens the stone with water, using a sponge, then rolls the ink onto the stone. The stone, like a thirsty camel in the desert, must stay ‘hydrated’ at this point, especially when being rolled with ink. Simply put, the damp areas repel the ink, whilst the previously drawn and treated areas, attract it.

Now, summertime, when the sun comes slanting in, warming the studio, is not the best time to do this, as I found out at Cork Printmakers, one simmering July afternoon. Keeping the stone sufficiently damp, between passes with the roller, is a race, in such conditions, against the elements. But all going well, after inking, the ghost image should once more appear as it was originally drawn.

After all this, and here is where it truly becomes a dark art, the printmaker-mage goes through the gum arabic process all over again. This is to ensure the ‘stability’ of the image for a large print run. Following another period of absorption, the image is once again inked up and printed using a litho press, keeping the stone damp all the while.

So, given the time-consuming, laborious process, why are artists today attracted to stone lithography? Firstly, printmakers by their very nature, enjoy discovering new processes, new ways to make an image magically appear out of the ether (or, in this case, the stone). They also enjoy the labour. In a fast, digital age, stone lithography is a way of slowing down, of stilling time. Then there is the drawing process itself: limestone is one of the most beautiful surfaces an artist can draw on, whilst the richness of the printing inks are unparalleled. Artists have, additionally, often collaborated with master lithographers, thus bypassing the more elusive, time-consuming and alchemical aspects of the process. Virtually every major artist who has ever produced an ‘artist book,’ from Miro to Matisse, has engaged with specialist studios in this way. Quite simply, it is a beautiful, limited edition means of reproduction.

Hopefully you are now looking at these printed words in a different way; the secrets that enabled their eventual journey to newsprint originated in an alchemist’s laboratory and a lithographer’s stone. Keeping the art alive are the stone whisperers, the copper kabbalists; pilgrims of print, ever magnetised by the mysterious elements of the earth and the riches they can bring.

A big shout-out to Dominic Fee, master lithographer, at Cork Printmakers, for his expertise and stone midwifery. In other news, the Clonakilty Arts Centre will be holding a ‘Save our Arts Centre’ rally on August 2, 2pm at Asna Square, the previous having been cancelled due to rain. I also must make a correction to last month’s column: I erroneously stated, that in West Cork, only Gallery Asna | Clonakilty Community Arts Centre, and Uillin curate year-round exhibition programmes. Working Artist Studios have been doing so in various locations since 2000. That’s some achievement; hats off to Paul, Marie and their team.