‘The great appear great, because we are on our knees: Let us rise.’

– Jim Larkin, Union leader, and Founder of the Irish Labour Party.

When any union goes on strike, be they nurses, rail workers, teachers, retail employees, the media usually likes to take to the streets to get a vox pop of public opinion. A typical response usually comes in the form of, ‘well, what about all the upheaval and inconvenience the strike will cause?’ It seems to me, some people are happy to support strikers, as long as they are not inconvenienced. But what would be the point of a strike if it didn’t upset the apple cart? I always thought that was the intention. One must remember – strikes usually are the product of a breakdown in dialogue or a failure of compromise between both sides. We live in a society where there is a malaise against unions as some sort of regressive anachronistic institution that holds our economy back. What so many of us take for granted is that our rights as workers have been hard won, not simply handed over. Part of the problem lies in the public versus private pitched battle that raises its head when industrial action is mentioned. The private sector can feel that unions hold the country to ransom, leaving them to hold the can. This divide and conquer is one of the oldest tricks in the book and has been used by the unscrupulous elite and powerful since the Industrial Revolution. The alienation between fellow workers, from different industries, is mainly fostered by the lack of a company’s willingness to recognise unions; or worse still, not allowing unionisation of a work force. Forty per cent of multinational companies, using an Irish workforce, do not allow their employees to unionise. That rises to 60 per cent if you work for an American company. Do not be surprised – the ‘land of the free and home of the brave’ has always fought hard against the unions throughout its history. So too did Churchill when he had to deal with millions of workers who found their voice after getting the right to vote at the end of World War One. By disbarring workers from unions, it weakens the supportive fabric of a unified workforce, thereby creating the conditions where unions are despised, rather than seen as beneficial organisations.

While all Irish employees have a constitutional right to join a trade union, there is, however, no legal obligation on an employer to either recognise or negotiate with that union. Worse still, is that the right to strike is not recognised by Irish law (thankfully, it is under EU law). Even then, a union has to meet strict conditions before they can strike, which means any union would have had to undertake a process before taking on industrial action. It’s not as ‘knee jerk’ as many of us believe. When we think of great Irish socialists like Jim Larkin, James Connolly, Countess Markievicz and Thomas Johnson, one would expect unions and Labour to have had more historical influence in Irish society. So why not?

Kevin O’Higgins, who was in the Irish Volunteers and a member of Sinn Féin in the first Dáil, went on to have a prominent position in the Irish Free State. Famously he remarked: “We were probably the most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a revolution.” Despite the massive slums in Dublin, often cited as the worst in Europe, a socialist revolution never happened in Ireland. TB was rampant in the tightly packed tenements and laneways of the city, with a death rate 50 per cent higher than other British cites. Yet, being chiefly an agrarian society, factories and slums may not have been as high on the agenda as one thinks. The Land Acts that were introduced in the 1870s evolved and made purchase a more affordable right into the early twentieth century. This largely enabled Irish people to purchase fairly their own land, thus ending landlordism and the dominant aristocracy. The War of Independence was never about land, because the land question had been largely solved before a bullet was fired. It was about political power and nationhood. The Proclamation advocated many fine ideals of this nationhood, and Padraig Pearse is credited with its creation. It also espoused some progressive socialist ideals, framed by James Connolly, a socialist republican. He was more aligned with the French revolutionary republicanism of ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ and his fingerprints can be seen on the Proclamation where it states, ‘Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts, cherishing all the children of the nation equally.’

Connolly didn’t create this in a vacuum; himself and Jim Larkin had literally fought for the workers in the 1913 Dublin Lockout.

William Martin Murphy, originally from Bantry, was one of Ireland’s most successful and influential businessmen. He was chairman of the Dublin United Tramway Company and ran the Irish Independent, amongst other enterprises. Not unlike some of the big companies today, he did pay his workers a fair wage but worked them hard in tough conditions. And in parallel with some companies today, he refused to recognise the biggest union founded by Jim Larkin, the ITGWU (Irish Transport and General Workers Union) and also refused to hire anyone who was a member of this union. It was this stance that was the catalyst for him firing hundreds of tram workers simply because they joined the ITGWU.

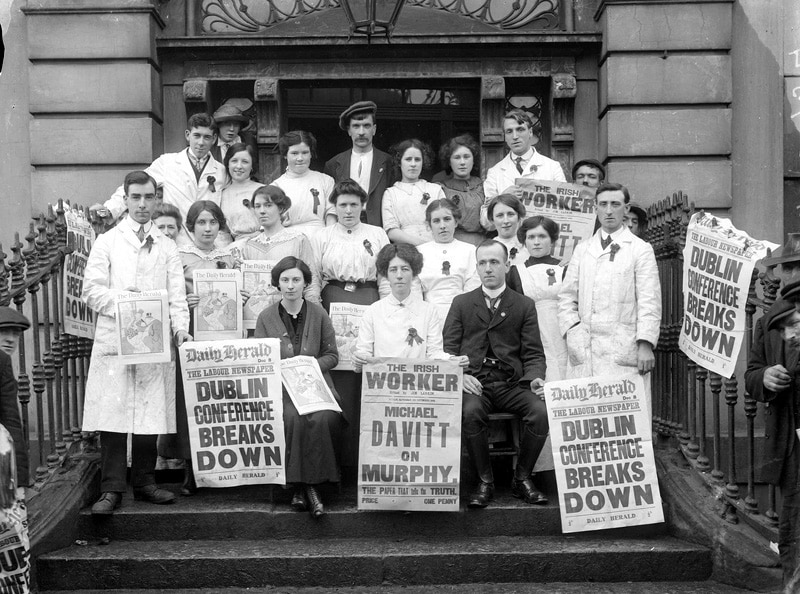

Larkin and Connolly encouraged union workers across the board to come out as sympathetic strikers, which they did in their thousands. What transpired was an example of the mighty few crushing the will of the majority. The employers, under the influence of Martin Murphy, struck back and locked their workers out of work without pay. The Catholic Church, then the epiphany of conservatism, sided with the employers instead of the aggrieved, downtrodden and hungry masses.

What happened next showed what workers could do if united. Nationality and religion should not, and did not, matter when the British Trade Union Congress sent over £150,000 to the ITGWU, to feed the starving families on the strikes. They even went further when they tried to initiate a scheme to foster the striker’s children in their homes in England, so there would be less mouths to feed. This spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood was broken when the Catholic hierarchy once again intervened, using their influence to claim that Catholic children would end up in Protestant homes.

If that wasn’t enough, another pillar of the Establishment physically crushed them. The DMP (Dublin Metropolitan Police) baton charged workers to break up strikes on August 13, 1913, resulting in two dead and hundreds injured. Connolly vowed that this would never happen again and set up the Irish Citizens Army to protest the worker. Significantly, men and women could join, unlike the Volunteers, and they took part in the 1916 Rising. (In contrast De Valera, who fought in Boland Mills in the 1916 Rising, was asked would he like assistance from Cumann na mBan, in the mill during Easter week. He turned them down, saying it was no place for women).

And so it came to pass, that the 1913 Dublin Lockout was defeated by the triple alliance of the elite business class, the church and the Establishment police force. A year later, many of these men would join the British army, out of economic necessity to elevate the poverty their families continued to endure. They would ironically be fighting so the elites of society could keep their colonies and possessions, and the yet majority of the soldiers, still could not even vote until 1919. A few short years after the Great War, many Irishmen fighting for the IRA found themselves pitted against ordinary ‘Tommys’, the same ‘Tommys’, who had donated money to their fellow Irish workers in 1913. Religion and nationally didn’t matter before, only empathy for a fellow worker. Now they were thrust into a cauldron where it was made to matter once more. Once again, it was a case of divide and conquer; when the common ground uniting them should have been their working-class grievances.

During this turmoil when Ireland was trying to assert its independence, the Labour Party chose not to contest the 1918 election in the interests of a united front based on self-determination. Would it have mattered? Arthur Mitchell, Labour historian, claimed that the party had not sufficiently appealed to small farmers or labourers, but overall lacked a large enough industrial base for support, in what was still a dominant agrarian and rural society. Some commentators believe that had they stood, it would have eaten significantly into Sinn Féin’s numbers. Either way, Labour left the other parties get a head start in the political race, which proved costly. Thomas Johnson, the Labour leader wrote the first draft of the 1919 Democratic Programme for the first Dail, though Sean T. O’Kelly watered down some of the left leaning policies, because he perceived it as ‘quite radical and left-wing in its ideology’. ‘Conservative revolutionaries’, indeed Mr O’Higgins.

I leave the last words to one of Ireland greatest playwrights – George Bernard Shaw. He was a philanthropist, socialist, and was one of the founder members of the British Labour Party. He wrote, ‘The first duty of every citizen is to insist on having money on reasonable terms and this demand is not complied with, by giving men and women three shillings each, for ten or twelve hours of drudgery, and one man a thousand pounds for nothing.’ Little has changed.