The Irish Government has committed to restoring biodiversity and mitigating against climate change but traditional forms of aqua culture like oyster farming affect our eco-system and degrade the security of wild populations. With the closing date approaching for written submissions regarding the application for a licence to farm oysters on trestles in Clonakilty Bay and local residents voicing concern, Fiona Hayes looks at the company behind the application, the impact such a farm may have on Clonakilty Bay and how government investment in restorative acquaculture could support the shellfish industry in Ireland to safeguard rather than destroy marine habitats.

AG Oyster Limited was set up as a company partially based in Dublin on Friday, December 11, 2015 and is listed as a ‘micro company’; which means that it has a turnover of €734,158 or less and 10 employees or less. However Adrien Geay, the sole director of the company, is also a director/owner of Huitres Geay, which has an annual revenue of $1 million (USD) and employs 20 people, and he is also director of Geay Production, which has 10 employees and generates $639,000 (USD) in sales. Adrien is the fifth generation of Oyster farm operators in his family in France and continues the family business that was started in 1874 in the Marennes-Oléron’s basin on the west coast of France and supplies Oysters to Tokyo and Singapore as well as to France.

As Climate change warms up Mediterranean waters however, Oyster farmers are looking at more northerly territories, where the cooler water is more conducive to growing the shellfish. Warmer temperatures raise the oyster’s metabolic rate, which raises its oxygen and energy requirements.

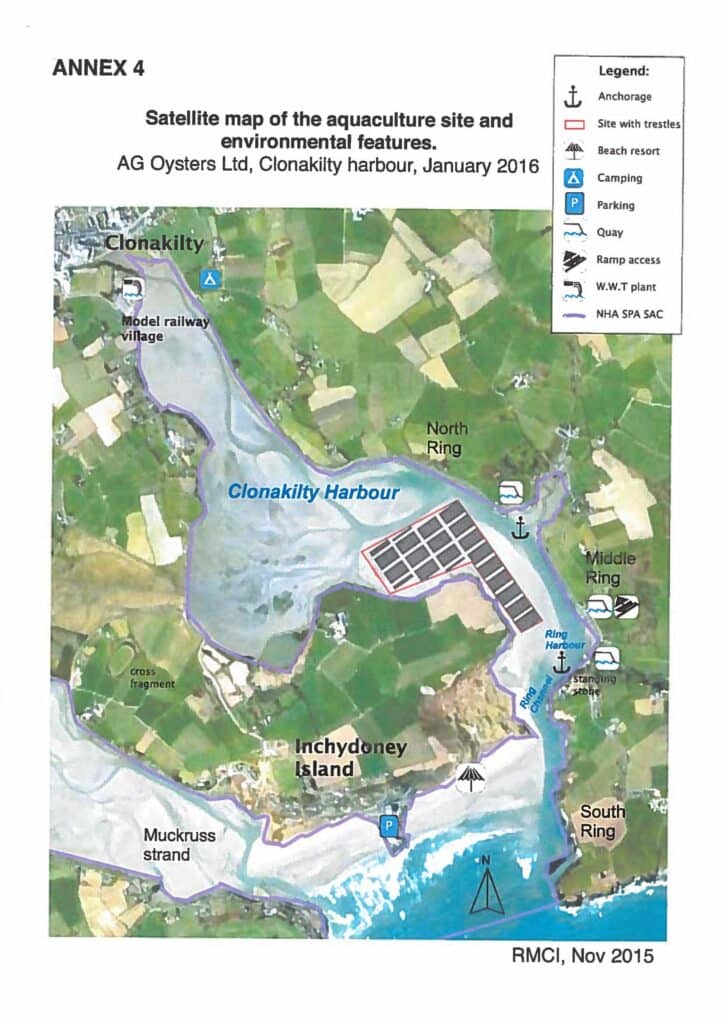

Adrien Geay, trading as AG Oyster Limited, has applied for numbers of licences to farm Oysters on trestle tables around the Irish Coast. To farm oysters in bags on trestle tables requires an intertidal area where the trestle tables are exposed at low tide. This allows access along the sand by tractors, trailers and workers; and in Clonakilty Bay he expects to eventually employ six full-time workers and some seasonal workers.

The oysters harvested will be sent to France for depuration, a process by which the oysters are held in tanks of clean seawater under conditions, which maximises their natural filtering activity, resulting in expulsion of contaminants before they are sold for human consumption.

The oysters that Huitres Geay/AG Oyster would grow in Clonakilty Bay are Pacific Oysters, a variety that originates in Japan and is listed on the Irish Statute Book as an invasive species. This listing is partly because it spawns prolifically competing with native oysters and partly because it can carry a small parasitic worm called Ceratstoma inornatum. This worm is an oyster driller that feeds on young oysters and mussels destroying whole populations of shellfish. In farmed populations of oysters it causes 25 per cent mortality. It is native to Asia and was introduced to other locations around the world by the stocking of Oyster Farms with Pacific Oysters. Sadly this worm not only attacks the farmed stock of oysters but also will attack Ireland’s native wild oysters and will attack mussels.

Ireland’s Native Oyster is ‘not’ the Irish Rock Oyster. That name is simply branding applied to the invasive Pacific Oysters farmed in Ireland. Native to Ireland is the much-depleted European Flat Oyster, currently being studied by The Marine Institute with a view to providing a project to restore populations.

Whilst Oysters farmed on trestles create a net loss of energy in the form of phytoplankton, extracted from the ecosystem, they also deposit organic nitrogen-rich bio-deposits to the bottom sediments. Bacteria then decompose these sediments forming ammonium.

Shading provided by the oyster bags and farm infrastructure; and farm activities, such as boat, vehicular and pedestrian traffic between and around the trestles, may have a detrimental impact on the flora and fauna such as the important seagrass beds; and is likely to compress the natural structure of the sea bed.

However oysters, in addition to being commercially valuable and a significant potential source of income for coastal fishing communities, provide valuable ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, maintenance of water quality and provision of a structural habitat that supports biodiversity.

Oyster reefs are one of the most severely impacted marine habitats on earth. A study led by The Nature Conservancy found that 85 per cent of oyster reefs globally have been lost due to over-harvesting, hurricanes, disease and changes in freshwater flows. This decline has serious consequences for marine and estuarine ecosystems especially those bays and estuaries that are plagued by eutrophication, often a side effect of the overuse of nitrogen based fertilisers. The nitrogen-based nutrients trigger dense phytoplankton blooms that occlude sunlight and create ‘dead zones’ under which life cannot be sustained. Shellfish are the biggest removers of excess nitrogen. They incorporate it into their shells and soft tissues, thus oyster reefs filtration can help reverse this eutrophication and consequent habitat loss.

A single adult oyster can filter more than 200 litres of water a day, removing excess nutrients, toxins and other pollutants and making the water clearer, which helps the seagrasses to grow, increasing nutrient availability for marine species such as crustaceans and worms. With the nutrients unlocked, oyster reefs can act as nursery areas, increasing the numbers of baby fish and thus increasing the fish stocks.

The ‘Supporting Oyster Aquaculture and Restoration’ (SOAR) programme run by The Nature Conservancy and funded by The Pew Trust advocates ‘restorative aquaculture’; a practice that pairs extraction with restoration in a type of circular economy. They postulate that the sea cannot be neatly portioned off, and that over-extraction collapses ecosystems. Many marine biologists believe that restorative aquaculture can create a positive feedback loop, increasing the productivity of marine ecosystems and benefitting the seafood industry in result.

The world’s biggest reef-restoration project is in Chesapeake Bay, Virginia where The Nature Conservancy (nature.org/en-us/) and Pew Charitable Trusts, along with multiple aquaculture companies, are creating 144 hectares of oyster reef. These are not trestle tables but are restored reefs which filter out $3 million (USD) worth of nitrogen annually, add $23 million (USD) worth of fish production to the waters annually and in this particular location, boost returns from blue crabs by $11 million (USD) per year.

As The Nature Conservancy and their partnerships have demonstrated, as well as being good for the environment Restorative Aquaculture is a wise investment; but for the benefits of Aqua Culture to be truly realised the distinction between restorative aquaculture and more traditional forms that degrade the security of wild populations must be recognised.

A whole report published last November – European Native Oyster Habitat Restoration Handbook – aims to provide foundational and practical guidance on the restoration and conservation of native oysters (Ostrea edulis) and native oyster habitat across the UK and Ireland (nativeoysternetwork.org).

With the public consultation to assess expanding Ireland’s Marine Protected Areas in full swing and the closing date for the receipt of written submissions regarding the application for a licence to farm Oysters on Trestles in Clonakilty Bay, closing on June 5, we ALL need to remind the government of their commitment to restoring biodiversity and mitigating against climate change.

There are other more eco friendly and more profitable ways of working. With the right support, the shellfish industry in Ireland can safeguard marine habitats – a responsibility that conservation bodies and the general public alone, cannot uphold.”

The closing date for the receipt of written submissions regarding the aquaculture application is June 5 and submissions can be emailed to APC@agriculture.gov.ie ahead of this date.

The public consultation on Ireland’s Marine Protected Areas runs to July 30, 2021. Submissions can be made online at gov.ie or by email to marine.env@housing.gov.ie or by post to MPA Public Consultation 2021, c/o Marine Environment, Dept of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Newtown, Wexford Y35 AP90.