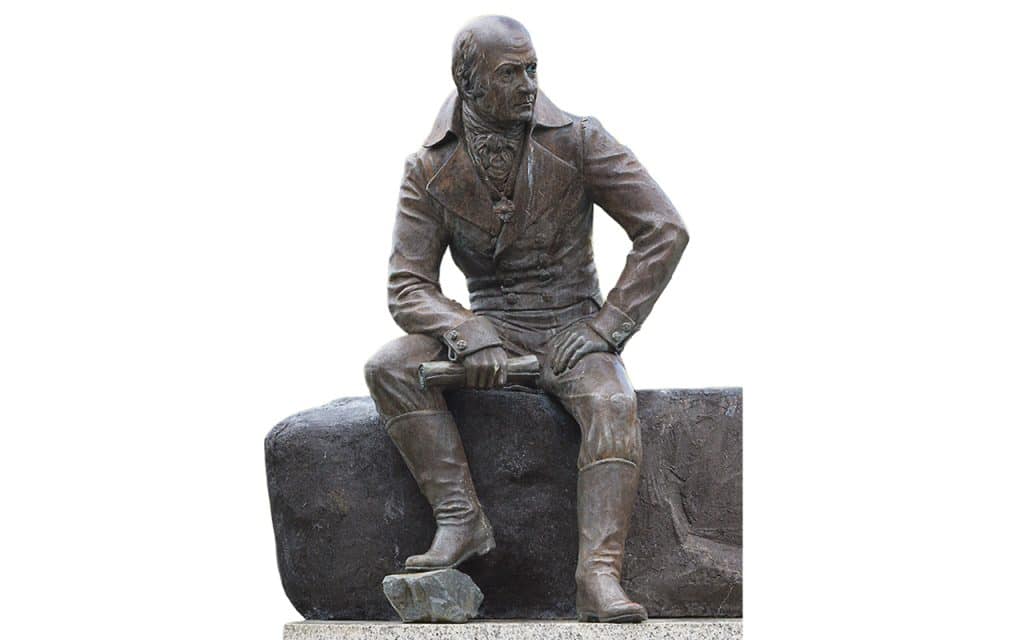

Six thousand miles away in the tiny Alaskan town of Sitka (formerly New Archangel – named after a Russian city), a place only accessible by boat or sea plane, much to the disgust of the local indigenous population, a statue of a Russian was erected on the town square in 1989. This decision was made in honour of Alexander Baranov, the man responsible for bringing commerce and trade here as part of the ‘Russian-American Company’ (RAC) organisation in what was deemed Russian’s first American colony in 1799. To widen the context a little, have you ever looked at a world map and wondered why Alaska is separated from the USA and not part of the Canadian territory it is adjacent to? The Europeans, including the Russian Empire, scrambled for potential riches of the new world. Under the rule of Tsar Paul I, an edict was released claiming “all the islands and coastland down to the 55th parallel” (modern Alaska). Just like that – a colony was carved up, regardless of the hundreds of thousands of indigenous people and their culture and religion. It was a dream that envisaged further expansion, one that would encapsulate a coastal empire as far south as northern California. It was a dream that was never realised. Why not? After all, in 1799, the USA was a very new nation, a century away from becoming a world power. It consisted of a thin sliver of colonies that hugged the east coast with a population smaller than Ireland’s today – not much of a danger.

Over the centuries, the Russians had been expanding east from Moscow all the way up to Siberia and Eurasia, driven predominantly by a lust for timber and fur. The small body of water that separates the USA from Russia, the Bering straits, is named after ‘Russian’ explorer Vitus Bering. (He was actually a Danish national but employed and funded by the Tsar of Russia).

Bering ultimately would fail. On his return to the Americas on a second exhibition, he perished on the island that was named after him, but had laid down a template for the ambitious, brash and destructive Grigory Shelikhov to follow. He had ambitions for a ‘New Russia’ yet had some convincing to do in persuading the then-Russian monarch Catherine, to fund and patronise his initial American venture in 1783. Much like Napoleon at his pomp, who sold greater Louisiana to the USA to fund his European ventures, Catherine was far more interested in the established, European theatre of influence, rather than the potential of a ‘new’ world. But Grigory Shelikhov was determined. He recognised the magnitude of the fur trade. China at that time produced goods that the rest of the world desired and coveted; silk, porcelain, tea. The Chinese themselves had an insatiable appetite for fur, in particular sea otter, (for its warmth, durability and texture) and thus there was a huge market for the Russians to monopolise, if they could.

His ventures would take him from the most eastern tip of Russia, and a voyage of discovery and cruelty inflicted upon the indigenous populations he encountered, across the Pacific archipelago off the mainland. It culminated in 1785 with the massacre of the Alutiiq, bringing about their ultimate serfdom. Shelikhov broke the Alutiiq resistance at Refuge Rock, near Kodiak island, massacring an estimated 3,000 natives, a battle often referred to as the ‘Wounded Knee Massacre’ of Alaska. (Wounded Knee was the destruction of the Lakota ‘Indians’ by the USA army in South Dekota in 1890).

However it was Alexander Baranov, who is credited with growing and keeping alive the hope of a Russian colony in America, serving as Russian’s ‘colonial governor’ from 1799-1818. It is to him that homage was paid to with the erecting of his statue in 1989. He dreamed of something greater than just trading posts. Places such as ‘New Archangel’, and ‘New Russia’ were some of the settlements that were born. The Russians even had a station in California, the Fort Ross colony in near present-day Bodega Bay, but in reality their settlements never amounted to more than trading outposts with small numbers of colonists – with Sitka peaking at 550 people at any given time. Yet they claimed vast swathes of land and would stubbornly defend them and their colonial rights for another half century.

So why did Russia fail to grow their colony? There are a number of reasons put forward by historians, both Russian and American. One is that it was never a colony in the proper sense of a settlement. People went to these outposts to embark on working opportunities, not new lives. Was work solely enough reason to settle? The harsh climate is often cited, but this part of the world is no different to north east Russia, where many settlers hailed from. It is certainly true that the colony, despite its lucrative trade in furs, was always in debt and needed constant supplying. The fur trade would eventually be exhausted and China would cool on furs.

In recent years, historians have given more scholarly attention to the role of resistance by native peoples. This was often underestimated or ignored by a generation of culturally superior ‘academics’ who didn’t consider it. There’s enough evidence to demonstrate that the interference of Spanish, British or Americans privateers, all undermined the Russian settlement, and all were impediments to its growth. But the greatest threat came from the local indigenous tribe called the Tlingit.

In this vast Pacific wilderness, location was everything. Baranov had set his sights on Sitka Island as the heart of ‘New Russia’ for a combination of reasons; accessibility to huge otter regions, shipping access and a gateway to unclaimed territory by Europeans. What he didn’t bargain for was the Tlingit who, unlike many other indigenous peoples of America who capitulated or were crushed, offered stiffer resistance. There is now more scholarly focus on how their resistance was the reason behind why Russian colonialism never actually established a strong foothold.

The Tlingit, like so many other native American tribes, were not just going to let Europeans take the land. Baranov, in contrast to the cruelty of the conquistadors in South America and later the Americans on the western plains of the USA, initially tried to implement a measure of diplomacy and coexistence. His longterm plan was that the Tlingit would eventually accept becoming Russian subjects. The fiercely proud and independent Tlingit somewhat reluctantly agreed to a trading post (after all trading could be beneficial both ways). As Baranov became more ambitious, and his colonists more aggressive, killing many Tlingit and oftentimes ravaging and raping some of the local women, the natives had enough and demanded that Russians quit their ancestral land.

What transpired was a war between the two, culminating in a defeat for the Russians in 1802, on a par with General Custer’s defeat at the ‘Battle of Big Horn’, but a lot more damaging. This was called the first battle of Sitka. In 1804, Sitka became the centre point of the battle at the mouth of the Indian river, where once again the Tlingit showed themselves to be more than able to match the Russians. On this occasion, a tactical retreat was taken and thus began the great survival march over a mountain range, consisting of a clan of 900 warriors, elders and families. Incredibly this was still not the end of the Tlingit of Sitka Island. Together with their other clan members in the greater region they created a trade barrier blocking outsider routes and neighbouring tribes from trading with the Russian outpost. They even encouraged English and American traders to isolate the Russians.

However the Tlingit defiance could not last, and not because of Russian might. What wore them down was a changing way of life. Nearly a million seals were killed for their fur in the North and West Pacific coast, culminating in their near extinction. Tlingit clans would be weakened because they could no longer live independently. In time they would have to work for the European newcomers and as a result the fabric of their society unravelled. But they had been detrimental to the colony’s growth, prospects and standing amongst Russians.

By 1867, Alaska had consequently been sold to the expansionist USA for 7.2 million in gold. Just a few short years later, gold was discovered in the Klondike region of Yukon in northwestern Canada promoting boom towns along the route through Alaska, which opened the floodgates for European settlers to migrate north, something Russia failed to do in this vast and oftentimes, indomitable land. Alaska would become a place of boom and bust towns, rising and falling over gold, timber and salmon. Even today its tiny population lives amidst the great mountains, glaciers and forests that seem almost as impenetrable a landscape as it was when Shelikhov, the self-proclaimed ‘Russian Columbus’, and Baranov, dreamed of a new Russia. Today there are tiny reminders of that dream; an old Russian Orthodox church in Juneau; placenames like Russian Square or the Russian Gardens in Anchorage. There is an island called Baranof (from Baranov) and there is a lingering number of Russian surnames to be found. But what defines them most today is the remembrance of the Tlingit and their totem poles. The tribe that stopped an empire.