“Maolra Seoighe was wrongly convicted of murder and was hanged for a crime that he did not commit…” – Michael D. Higgins

On December 15, 1882, Maolra Seoighe was convicted of murder and hanged. One-hundred-and-thirty-six years later, in 2018 – after it was discovered he was innocent and had been incorrectly sentenced to death – he was pardoned of the crime. In pardoning Maolra posthumously, President Michael D. Higgins said the case itself was a miscarriage of justice and linguistic discrepancies had played a part in his wrongful conviction. The interesting curiosity in Maolra Seoighe’s case is that he was a monoglot: He solely spoke Irish and had no English. His case was tried in English and he could not understand his defense lawyer, the judge, or the jury. Speaking in Irish throughout his hearing, at all stages he vehemently denied the allegations put forward against him. More famously known as the Maamtrasna Murders Case, Seoighe was accused of killing five members of the same family to whom he was related. The victims were the Joyce family, all killed in a very peculiar manner: The men were shot and the women were bludgeoned over the head with such force that their brains were found outside of their skulls.

Irish Language translation is the focal point of this story. Recently Independent Cork County Councillor Diarmaid O Cadhla, a fervent Irish speaker, had his case adjourned because he insisted on conducting his trial ‘as Gaeilge’. Judge Olann Kelleher granted his request, adjourning the trial until an Irish translator could be employed to translate the case for which Mr. O Cadhla was required to answer. In the case of Maolra Seoighe, the failure of the courts to translate from Irish to English is the hinge on which the point pivots; for the purposes of simplicity the courts did not use Maolra’s actual name, instead choosing to use a rudimentary English translation in which Maolra Seoighe became Myles Joyce – the namesake of the family he was accused of killing. In the play ‘Translations’ by Brian Friel, the objective is to portray a lyrical exposure of the failure of the English language to express Irish sentiment. In the case of Seoighe and the Maamtrasna Murders, the failure of the Irish language to be granted the reverence it deserved, allowed a linguistic loophole to evolve from just that, into a genuine life and death scenario. A scenario that played out in a packed English-speaking murder trial courtroom, in which an Irish-speaking innocent man was the protagonist.

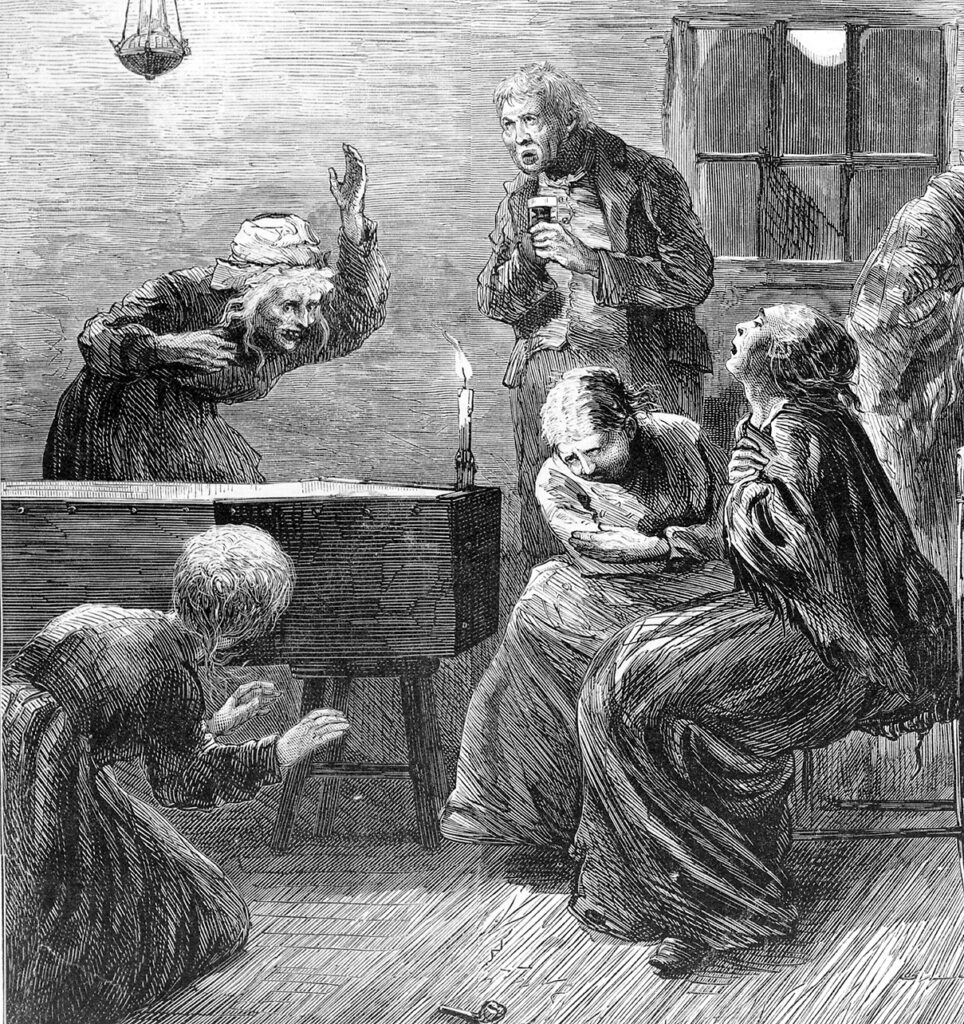

The unfolding drama of the case portrays a kind of raw cruelty that has enthralled a wide range of the public since the murders were committed the night of August 17, 1882. Maamtrasna is a remote village roughly 40 miles from Galway City, with less than 24 cottages. Maamtrasna, in the barony of Ross, in which Myles Joyce lived, had a population of 8,260, of which 7,350 people were Irish speakers and over half of these (3,714 people) spoke Irish only. Who spoke what language was imperative in the Maamtrasna Murders trial. The victims were a married couple, Bridget and John Joyce, two of their children, Margaret and Michael, as well as John’s mother, Margaret. They were found in their home, beaten to death. In total, 10 men were arrested in connection with the murders, two of whom, Anthony Philbin and Thomas Casey, spoke English very well. They used this to their advantage, testifying against the other eight accused. As a result, five pleaded guilty and were sentenced to prison. The remaining three, including Maolra were tried, convicted and hanged. Maolra was the third man in the dock to be questioned.

From the outset, the investigations failed to take account of the need for accurate translations of eyewitness statements. Even the jury of 18, that was sworn in to pass judgement on the case, included monolingual speakers with very limited understanding of what was unfolding in front of them. An interpreter was employed by the court for the trial, Constable Thomas Evans, a member of the RIC. Evans was a Protestant and a member of the Protestant Evangelical Branch, which is assumed to be where his knowledge of Irish originated.

The Freeman’s Journal an 1882 publication reported that; “At the sitting of the court, the attorney-general asked the learned counsel for the defense if the prisoner understood English.”

Henry Concannon was the defense solicitor representing Maolra. The reply the attorney general received was; “Mr. Concannon replied that he thought he did not, and that it might be better to have the evidence of the witnesses who speak English interpreted to the prisoner in Irish.

“The interpreter asked the prisoner in Irish if he understood the evidence that was being given in English, and informed the court that the prisoner replied in the affirmative.”

Here lies possibly the most important detail of the entire case. A translation issue and crucial mistranslation resulted in a vital miscommunication. Concannon, incredibly, was unsure as to his client’s knowledge of English and requested the services of an interpreter. Myles Joyce’s answering “in the affirmative” (namely, that he understood what the interpreter said in Irish) was taken to mean that he understood evidence given in English. Because of this, the service of the interpreter Constable Thomas Evans were deemed to be no longer needed in the course of the trial and Evans was only brought back into the courtroom to announce the guilty verdict.

The jury in the case of Maolra retired at 3pm on Saturday, November 18, after deliberating for six minutes in which they decided Maolra was guilty. The trial transcript records show that at this point Evans was recalled to the courtroom in order to give Maolra’s response to the guilty verdict.

A clerk in the courtroom asked: “What have you to say why judgment of death and execution should not be awarded against you according to law?”

Maolra replied ‘as Gaeilge’ to the interpreter. Constable Evans translated as follows;

“He says that by the God and Blessed Virgin above him that he had no dealings with it any more than the person who was never born; that against anyone for the past 20 years he never did any harm, and if he did, that he may never go to heaven; that he is as clear of it as the child not yet born; that on the night of the murder he slept in his bed with his wife that night, and that he has no knowledge about it whatever. He also says that he is quite content with whatever the gentlemen may do with him, and that whether he be hanged or crucified, he is as free and as clear of the crime as can be!”

Both Patrick Casey and Patrick Joyce stated that Myles was innocent, even as they accepted their own death sentences. Furthermore, the two men of the 10 initially arrested, who gave evidence against the other eight in return for leniency, retracted their statements after Maolra was hanged. It would later emerge that one of the men that gave evidence was nowhere near the crime scene on the night in question and it would have been impossible for him to have known who was guilty.

Due to pressure from the Seoighe family, the case was reopened; and with undeniable evidence proving beyond doubt that Maolra was innocent of the crime, in 2018 President Michael D. Higgins saw fit to pardon him.