Be safe, listen to the experts and behave responsibly

As I write this article, I am conscious of how the current Covid -19 pandemic, is even affecting this very article. The editor of the West Cork People, Mary O’Brien, communicated to us that this month’s edition, was to be only an online version. The paper, like so many other parts of industry and society, is going into their own self-isolation, for the benefit of the public. For the first time since its conception, the West Cork People will not be printing a physical copy. With many pubs, restaurants, leisure centres closed down and less people about, we are writing ‘remotely’ to you.

As I pen this article, in the latter half of March, my job too has been affected by the spread of the virus and the phrase ‘teaching remotely’ has been coined for many of us. Delivering lessons online might sound modern and easy. However, I think I am speaking for the majority of teachers, in saying that the interaction, influencing and shaping of our students personally and daily, is what we cherish, more than simply ‘posting’ a lesson. Yet we are the lucky ones. Please God when this is over, we can return to our jobs. This may not be the case for many people, though our government is acting fast to address the economic uncertainty facing so many of society. In 2009 the people of Ireland bailed out the banks. In 2020, we hope the banks will stand up to the plate, and bail out the people. So far mortgages have been suspended for three months – a great start, but the repercussions of this pandemic may ripple further than we realise. Whatever the economic cost, the emphasis quite rightly for now, is on the human cost and protecting our people.

Mary suggested, quite rightly, to looks for ways in our writing to boost people. Many will do so. Yet I felt the need to use this opportunity to reflect on the last pandemic – the Spanish Flu. Too many falsehoods have been infecting social media, which is leading to concern, panic buying and unnecessary stress for many families’ and vulnerable people. Despite the government’s best efforts and Tony Holohan and his medical experts’ advice, behaviours still need to change if we want to beat this. We are being asked to learn from the mistakes of Italy. Perhaps we can learn from the past too. This article is based on author and researcher, Ida Milne’s book, ‘Stacking the Coffins: The Influenza, War and Revolution in Ireland 1918-19’. Though we can draw societal parallels, I want to stress to readers, that this was a very different type of flu to the Corona virus. I write this with a certain hesitation, bearing in mind how people may have been affected by Covid -19. But I also write it, because I feel a duty to be one of the many voices, asking us all to behave responsible to help stop its spread. In 1918-19, they didn’t have our knowledge of medicine or our ways of communicating. One hundred years on from that devastating pandemic, we know have more tools to cope. But ultimately it still boils down to just one thing – our behaviour.

Why was it called the Spanish Flu?

We now understand the flu did not originate in Spain. So where did that moniker for the flu come from? When the first high profile case became public, it was reported that King Alfonso of Spain and many of his courtiers had contracted this mysterious malady – dubbed the Spanish Flu – and as we know, names stick. How did this pandemic break in the media? First and foremost, unlike the Covid 19, it was not the main player in town. The Great War was still raging and obviously newspapers were preoccupied with the outcome of the war, which was still in the balance. The British Government were looking to impose conscription in Ireland to generate numbers to bolster their battered and broken army, for the ‘big push’, against an equally devastated German Army. Thus in the papers, the conscription crisis, war and anti-recruitment stories were initially more prevalent. On top of this, the spread of disease was not uncommon in that era. In 1918, people still lived in a time where there was no cure or vaccination for massive killers like Tuberculosis, Measles or Polio. While we have a housing problem in the 21st century, there were very different housing problems in the early 19th century. Due to penury and poor economic prospects, folks had little choice but to live in the overcrowded and unsanitary tenements in the cities. Thus the outbreak of disease and was not uncommon, or necessarily, headline catching.

Outbreak

Looking at the 1918/19 outbreak and the response from governments and local authorities, it has strikingly strong parallels to what is currently happening in Ireland and globally. I want to explore the effects of the virus in 1918/19 and how people and communities reacted to it. I stress once again, though lessons can be learned from it, we cannot super-impose what happened in 1918/19 on to what may happen now. It is a very different world and there are more changing variables each day. However, what history does show us, that when faced with the spread of a pandemic, there is only one effective way to deal with it – social distancing, which in its extreme from means lockdown.

Ida Milne’s extensive research produced figures of 23, 288 deaths from the virus in Ireland [which in 1918 was 32 counties]. The amount of people who were estimated to have contracted the disease was 800,000 and thus the fatality rate was 2.5 per cent. This is not so different form the approximately three per cent mortality rate for Covid-19. [Though Italy, frighteningly, is running at a 10 per cent death rate]. A massive difference was that the Spanish Flu paid no heed to age or fitness. Wexford’s champion handballer, Dan Farrell, died from pneumonia, and even more worryingly, only a few weeks after he seemed to have recovered from it. Louth’s top intercountry footballer Joe Ross, succumbed to the virus too. Currently as I write, Italy, France, California and Spain are in lockdown in an attempt to flatten the curve. Ireland and other countries have introduced a partial lockdown and social distancing. Just a few short weeks ago, it was questioned whether lockdown was a disproportion response to the disease. If we can ascertain anything from the Spanish Flu, we can learn that communities and local health boards began closing events and places to stop the spread of the contagion. There wasn’t quite the same national blanket reaction or ability to communicate on a wider basis, so the responses seemed to be more community-orientated. Initially paper editorials ran stories criticising the British government [covering Ireland also] for its lack of strategy in dealing with the disease. The same criticism has been made of Boris Johnson’s leadership in the face of the Covid-19 storm – how history repeats itself when we don’t learn from it!

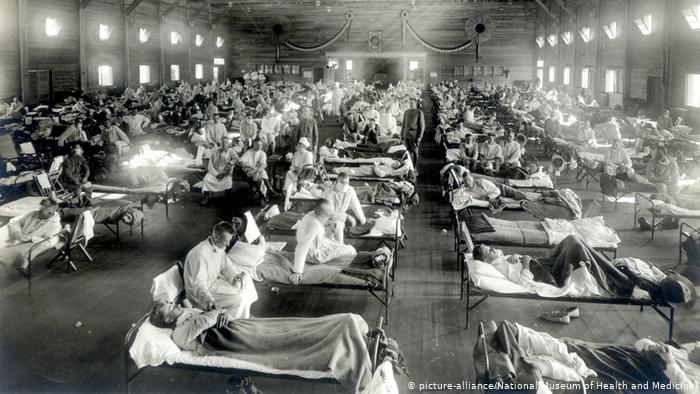

Hospitals were under massive strain. Whole workhouses were full and many families were confined to their homes, with no one to care for them. Doctor Pierse in Wexford strongly advised against the tending of wakes. Today, funerals are taking place but there have been calls to have little to no physical contact with mourners. Churches are one of many institutions that have been affected by the enforced closure of Covid-19. In my research for my book ‘Behind the Wall –the Rise and Fall of Protestant Power and Culture in Bandon’, I discovered that yearly accumulated church attendances in the two Protestant churches in Bandon fell by 1,390 between 1913 and 1919, extraordinary, in a town of only 499 Protestants [1911 census]. Surely the Great War was not the only factor in this dramatic fall?

In spite of hygiene not being practised at the same level as it is today, there were many theatres and shops disinfecting their premises and ‘businesses were being liberally sprinkled with antiseptic fluids’. Sport like today, was a massive part of society and it suffered too. Ireland sporting calendar has been wiped out. Gold riband events like the 1918 All Ireland hurling final between Limerick and Wexford was postponed until 1919. Sir Charles Cameron closed the schools, as the pandemic progressed, but was reprimanded for not going further and closing down music halls, theatres and picture houses. Eventually they did. A few days ago the government informed us that 200 prisoners have been released from various jails in case of an outbreak in prisons. There was a similar call to release political prisoners in 1918. One Sinn Féin internees, James Toal, died of that flu and their founder Arthur Griffin, was very ill while in captivity. A major problem at the moment is the panic and hysteria being caused by fake or misinformed ‘What’s App’ messages. Yet hysteria was also found in 1918/19, commented upon by doctors reporting to papers, in order to control ‘influenza hysteria’. One doctor quoted in the Democrat newspaper said, ‘there is a danger that the people may become panic-stricken by exaggerated accounts of the ravages of the epidemic and thus help on the disease.’ The HSE has dropped the embargo on nursing and medical staff in an attempt to prepare for an increasing wave of the disease. Many Irish medical personnel are selflessly returning home from abroad to lend their expertise to the fight against Covid-19. Ida Milne, tells us many frontline doctors in 1918/19 caught the disease and because of the shortage of physicians and nurses, ‘Many had to continue working beyond which was wise to do so’. Sound familiar? Shopping habits changed too. One leading grocer remarked that ‘the great bulk of his customers were sending in written orders by messages rather than coming to collect them themselves’.

Milnes book is a fascinating read and makes you ponder on how society responds to pandemics. For all our modernity, very little has changed. It amazes me why some countries like the UK and USA took longer than others to grasp this, but as Milne said herself, she too was amazed how we have forgotten the historiography of one of the world’s most devastating pandemics, which was estimated to have cost 50 million lives globally. While history isn’t a crystal ball, it should be heeded. It is worth stating that this pandemic came back in three waves. It started in the spring of 1918, reappeared in the autumn of 1918, before a third wave hit again, in late spring of 1919. We might have to prepare for a longer haul than expected. And please learn from our ancestors. They too had to suffer the loss of loved ones, closures, layoffs and practise social distancing – but they did overcome it. So will we. Be safe, listen to the experts and behave responsibly.