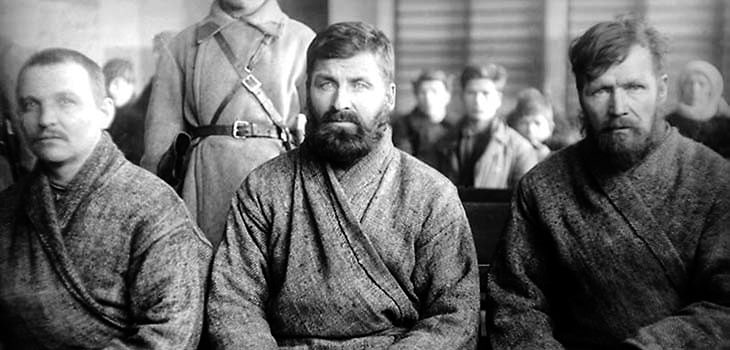

Defendants in the Moscow Show Trials of the 1930s.

Within these past few weeks, Trump’s audacious attempt to broker a peace deal in Ukraine, if accepted, could result in a humiliating defeat for Ukraine and a justification that if a bigger country like Russia wants something, then they can go ahead and just take it. The offer on the table would require Ukraine to cede territory that is currently occupied by Russian forces, as well as additional territory that is not. Ukraine would also be required to restrict the size of its army, while Russia would face no such limits. The proposal would give Russia joint control over a Ukrainian nuclear power plant, the largest in Europe. It would permanently bar Ukraine from joining NATO. Finally, it would allow Russia to rejoin the G8 and reintegrate into the global economy as if nothing had happened. When I broached the subject with two of my senior Ukrainian students, expecting them to share my disgust at this proposal, I was taken aback by the response: “I just want to go home,” “I just want the bombing to stop.” My armchair political analysis was superseded by the most human of reactions – the lore of home, family life and normality.

It’s almost four years since Putin’s Russia invaded Ukraine, which has certain parallels to Stalin’s invasion of Poland in 1939. Both wars have resulted in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of people. Both conflicts have centred on attacks on civilian towns and infrastructure, resulting in a mass exodus of refugees. And both conflicts have destabilised Europe. Another interesting comparison between then and now is that Western allies did not commit any troops into the theatre of war to defend the invaded territories. Stalin was a dictator ruling the USSR from 1924 to 1953, while Putin is a dictator in all but name, serving five terms as president or prime minister from 1999, doing so by changing the constitution that has allowed him to serve until now. Indeed, further constitutional amendments mean he ‘legally’ can remain in office up to 2036, thus surpassing the ‘Man of Steel’s’ thirty-year grip on the sceptre of power. Who would have thought this could happen again after the USSR was dissolved in 1991? It prompted the now infamous (and erroneous) political belief that the end of communism would now mean that western liberal democracy would become the victorious, final form of human governance – a kind of Darwinian political survival of the fittest. How wrong was Francis Fukuyama, the American political scientist who coined that phrase ‘End of History’ and wrote a book on it in 1992?

Instead we are in the midst of an era where illiberal and intolerant democracies and overzealous nationalist governments have blurred the lines between the independence of their judiciary and the reach of their rule. Perhaps Francis Fukuyama might be tempted to rebrand his as: ‘End of History for Liberal Democracy’. From the USA to Brazil, Hungary to India, Russia to Israel, the once vociferous voice of the free people is turning into a weakened whisper. Governments in these countries conflate criticism with anti-patriotism. We must not take for granted what we still have in Ireland – genuine freedom of our press, debate and our expression.

What is really a key component for any dictatorship is the control of media and thus public opinion. Putin creates laws that criminalise criticism of Russian military operations in the media and restricts foreign newspapers. In 2024 81 European broadcasters were banned from airing in Russia. His latest battle is to control individuals’ access to information that is not censored and controlled through their state media outlets. SnapChat has been banned, Apple FaceTime blocked, and WhatsApp is next, throwing a blanket further on the sharing of any stories that run counter to the Russian official line.

Stalin of course didn’t have to worry about digital or broadcasting media. Neither was he too concerned about print media, given that so many of the population of the USSR were illiterate and over 130 different languages were spoken across its landmass that spreads halfway around the globe across eleven time zones. But he was keen to get his message across to the masses. What was the best vehicle to do this? The trials of the 1930s. Invent a crime – one that betrays the state and therefore the people – make the message a simple one and punish mercilessly anyone who opposes you. Do it all in front of a judge and legal system in order to lend an air of legitimacy – even to foreign ears – and you have your magic formula.

There were three major ‘Show Trials’ in USSR during the 1930s. Stalin had seized control after Lenin’s death, though he was not his ‘anointed man’. Stalin had what Putin has: an unshakable belief in his own dogma. He executed 20,000 people in the early years, withstood all contenders, the most notable of whom was Trotsky, who fled to Mexico where he was eventually assassinated by Soviet agents. He was determined that the socialist revolution was to be led via the urban worker, to the detriment of the masses of peasant population who had to feed the urban Soviets. This would lead to collectivisation of their farms, widespread famine and subservience of the more well-off Kulak peasantry. Putin, likewise, has eliminated politically and by force, his political opponents, most notably Alexei Navalny, who was poisoned, an act widely attributed to the Russian state. When Navalny bravely returned home to rally his supporters, Putin had him imprisoned, and after a corrupt trial, he died in jail. Since then, it has become law that any Russian living outside of Russia is prohibited from running for office – a rule that affects many who fled the country to escape censorship for speaking out or to avoid unfair imprisonment.

Alex Navalny in court as part of the Kirovles trial, 2013.

Step back to 1936. The economy is not going well, and Hitler’s rhetoric against the USSR and communism is growing louder and more aggressive. Holding a trial that revealed an internal ‘danger’ would serve as a way to rally support and send an unmistakable message to the population that Stalin maintained complete control. It would also carry enough weight to have a disciplining effect on all the international communist movements that were attempting to foster communism abroad in their host countries. But not just any kind of communism – it had to be Stalin’s kind of Russian communism. The evidence used in the trials were a set of confessions from the accused that corroborated a conspiracy to overthrow the state through the assassination of key leaders. The accused were aware that these confessions would almost certainly result in their execution, yet they were still coerced into giving them. It also closed any debate. If they all agreed to their guilt, then there could be no rousing defiant defences or speeches that might capture the imagination of anti- Stalinists. The trial of course appeared legitimate. This is a task Putin has failed at – persuading international audiences that there is any semblance of fairness. On the other hand, the key prosecutor of the 1930 show trials, Andrei Vyshinsky, carried that air of legitimacy. He had a dress sense that caught the eye of British observers. One commented that he looked “like a stock broker from the city…a reliable kind of chap”. The American ambassador called him sober-minded, capable and wise. Years later, in the 1950s, he visited London, and the young Princess Margaret was eager to meet him because of his notorious prosecutions! Show trials by their nature imply a propagandistic element to the whole proceedings. They suggest a false narrative, a pretence that masks a dictatorial system that controls the judiciary. But Stalin succeeded in convincing his people and, for a while, the international community, of the authenticity of the proceedings

Comparing politics from different eras within a country is not straightforward given the prevailing conditions of any given time. Putin could not possibly get away with mass purges of Stalin. But mass jail sentences ultimately do the same thing. Silence opposition. Both men have a natural fear of the West – perhaps with good reason. Napoleon, Hitler and the collapse of the Soviet Union have all come from western assaults. The Russian Bear does not like to be poked. Throughout its long history, Russia has rarely experienced any form of liberal democracy. Instead, it has progressed from dynastic, feudal Tsars to communism, then dictatorship, followed by a one-party system, a brief experiment with democracy, and now a Putin-style autocracy. But it has been the Russian way. George Orwell, a contemporary of the 1930’s proceedings, observed. “What was frightening about these trials was not the fact that they happened – for obviously such things are necessary in a totalitarian society – but the eagerness of western intellectuals to justify them.” Perhaps that is the difference between then and now. For all our problems across the globe today, thankfully we can say we live in more enlightened times, and are more equipped to challenge the word of leaders who claim to be the voice of the people. This does not magic away all the horrendous conflicts; Sudan, Palestine, Ukraine and the many other regimes that suppress their own people. But there are enough dissenting voices out there that whatever or wherever the next show trial is – we will at least ask questions, look at the sources and view the evidence for ourselves. As long as we do that, there is always a chance.