Last month, I mentioned a fish called a lumpsucker; some of you might not know exactly what it is. Cyclopterus lumpus is a strange creature that lives in the cooler waters of the north Atlantic. The Latin name can be translated as ‘lumpy circular wing’; which refers to its knobbly, rotund body and the pelvic fins which are modified into a round sucker on its ventral surface. It is an ugly fish, but in a rather endearing way. It has many alternative names, e.g. lumpfish, stone clagger, sea owl and sea hen; the male is known as a cock paddle, the female a hen paddle. The Swedes call it sjurygg, or seven ridges, because of the rows of knobs along its back and sides; they also have different names for the sexes – stenbit for male, kvabbso for female. In German, the lumpsucker is a seehase, which means, quite inappropriately, sea hare.

Lumpsuckers belong to the family Cyclopteridae, part of the very large order Perciformes. There are 23 species, but only C. lumpus is found in this part of the world; four species live farther north in the Atlantic, the rest in Arctic or cold North Pacific seas. Lumpsuckers are related to the equally ungainly and confusingly named sea snails, two species of which may be found in shallow waters around our coasts.

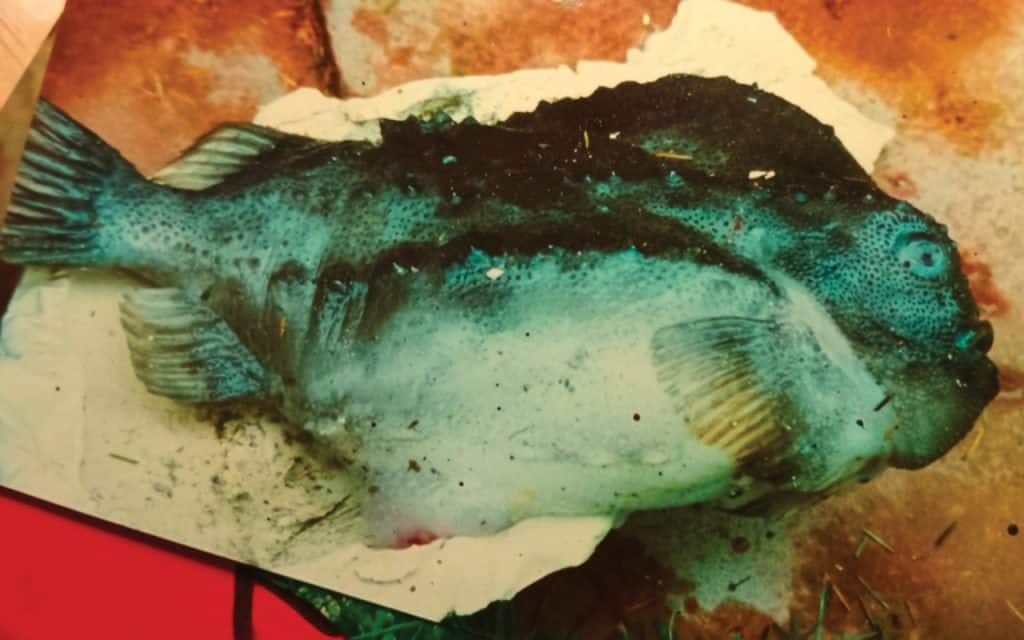

Lumpsuckers spend much of their time in deep water, down to about 200 metres, where they feed on planktonic organisms such as jellyfish and various small shrimp-like creatures. In the breeding season, spring and early summer, they move close inshore. The female can grow to a maximum length of 60 cm, and when full of eggs, is an obese, almost ball-shaped fish. Males are much smaller. Colours can vary, but they are usually a dark blue or greeny grey, lighter underneath. In the breeding season, the male develops an orangey-red belly.

They were given the chicken-related names because of the care with which they look after their eggs. The female lays up to 200,000 eggs, in rocky crevices above the spring tide low water level. Then she heads off back out to the deep sea, leaving the male alone to stand guard, attached by his sucker to the sea bed so he won’t be washed away. At very low tides, the eggs can be uncovered and some get eaten by seabirds, but the male stays with them, even if gulls peck holes in his back. He presses his nose into the mass of eggs to ensure aeration, he fans them with his fins, and he removes crabs, starfish or other predators, as well as any detritus. He is a very good parent.

Once hatched, the young fish spend their first few months in the surface plankton. You can sometimes find them hiding in clumps of drifting sea weed; they are adorable little things, coloured bright turquoise. At the surface, they are preyed upon by seabirds. As they grow, they descend to deeper water; their remains have been found in the stomachs of anglerfish, halibut, Greenland sharks and sperm whales. A blue shark on my boat once regurgitated a small adult. Seals also eat lumpsuckers and, according to the 19th century Cornish naturalist Jonathan Couch, know how to rip off the thick skin and eat only the soft flesh.

Lumpsuckers are not very important commercially; at least, they weren’t until recently. In Canada and the Nordic countries, they are fished for their eggs, which, when salted, pasteurised and dyed black or orange make a cheap substitute for caviar. In Sweden, it is common at Easter to have hard boiled eggs covered in mayonnaise and topped off with a dollop of lumpsucker eggs. The flesh of the females is not considered worth eating, but my old Scandinavian cookery book has recipes for ‘inkokt stenbit’ (male lumpsucker cooked in court bouillon); ‘stenbitsaladåb’ (male lumpsucker in aspic) and ‘Skånsk stenbitssoppa’ (male lumpsucker soup from Skåne). Couch wrote that “the taste is mawkish and unsubstantial, the flesh dissolving in the mouth like mucilage or oil”. However, Man has found another use for the lumpsucker.

Most fish have external parasites, generally known as sea lice, though they are not lice but crustaceans, either copepods or isopods. The latter are large – like woodlice; the parasitic copepods are much smaller. Many are host specific, e.g. garfish are mostly parasitised by an animal called Caligus belones; the blue shark by Echthrogaleus coleoptratus. In the wild, fish either put up with the parasites, or they go to special places where they know that cleaner fish, especially species of wrasse or shrimps, will be waiting. Sharks carry their own skin-care specialists with them – remoras, those strange fish related to scad whose dorsal fins have been converted into large suckers.

Garfish often have many parasitic copepods on their gill covers; very large infestations result in holes bored right through the bone into the gills. It is thought that their habit of leaping out of the water is sometimes an attempt to rid themselves of parasites. In early summer in Sweden, garfish migrate from the North Sea, through the Kattegat into the Baltic, where, in less saline waters, the parasites fall off. Similarly, wild salmon collect ectoparasites at sea, and when they migrate into rivers to spawn, the parasites die. But when large numbers of salmon are kept in cages at sea, the parasites have a wonderful time: they eat the skin, flesh and mucus of the salmon, creating open wounds which can cause stress, the introduction of diseases, death and, of course, loss of profit. So fish farmers have to add chemical delousers to the water to kill the parasites. Unfortunately, such chemicals are probably harmful to other crustaceans, so now cleaner fish are kept in the salmon cages. Most of these cleaners are various species of wrasse, but it has been found that lumpsuckers grow more rapidly than wrasse and survive better in colder waters, so since 2011, they have been bred specially and used in Norwegian and Scottish fish farms.

Biological control of pests is obviously better than using chemicals, but life for cleaner fish in salmon farms is not much fun. Caged salmon, unlike wild fish, are not always grateful for being cleaned and will eat their cleaners. And while wrasse are natural cleaner fish, lumpsuckers are not; studies have found that not all of them like eating sea lice and many die of starvation. Lumpsuckers in the wild can live up to 14 years; in salmon cages, they rarely last a year. So the poor lumpsuckers are forced into an unnatural existence, starved of their normal prey, sometimes attacked or infected by salmon, not allowed to swim into the shallows to breed, and unable to use their suckers to rest on the seabed. They have been turned into tools, not considered as sentient animals. Here again, nature is made to suffer, like the seabirds and cetaceans deprived of food by the capture of sprats and krill to make fish meal for fish farms. But most people don’t think about such things while they nibble their smoked salmon canapés.

I got to know lumpsuckers for a different reason. Many years ago, my academic career having stalled (there wasn’t much demand for garfish experts) and my old angling boat rendered illegal and uninsurable by new safety regulations, I taught myself fish taxidermy. I thought that with all the anglers who used to fish from Courtmacsherry, some might like to have their best catches mounted and preserved for posterity. They rarely did. But a friend of mine, a commercial fisherman, used to bring me odd fish to examine; they were already dead, so I thought I might as well make use of them. In four years, I prepared 104 fish, including wrasse, lumpsuckers, trigger fish, gurnards, dragonets and boarfish, as well as many crabs and lobsters that had gone bad. The easiest to work on were lumpsuckers: they have no scales to fly off, their skins are tough and leathery and their skeletons almost totally cartilaginous. And when mounted, grotesque as they were, lumpsuckers proved the most popular.

But it wasn’t a successful venture, and I barely made enough money to pay for plaster, paints and preservatives, which was just as well – I wasn’t happy trying to earn a living from dead animals. And that was in the nineties when, so it seemed, the Celtic Tiger was bestowing second homes, third cars and Polish au pairs upon the humblest of villagers (and removing much of Ireland’s traditional amity), while I was still living in a leaking caravan, alone but for a fat cat and dozens of unwanted stuffed fish. That is why I went abroad and became a wandering school teacher.