Easter Sunday may fall on any date between March 22 and April 21 with a wealth of lore and customs attached to Holy Week.

People in all parts of Ireland held to the pious belief, common in many parts of Europe, that on its rising on Easter Sunday morning, the sun dances with joy at the Saviour’s resurrection and may be seen dancing on the surface of a lake or river. Generally it was held that one should go to a hill top or other high place to view the sun properly. St Patrick used bonfires to celebrate Easter since the Irish were used to honouring their gods with fire, and bonfires are still lit in some areas on Easter morning to herald the dawn. Mass is celebrated outdoors, usually on top of a high hill, in some areas on Easter Sunday morning. The Pascal Candle, decorated with studs to depict Christ’s wounds, is lit at Easter and is burned from Easter to Whit Sunday.

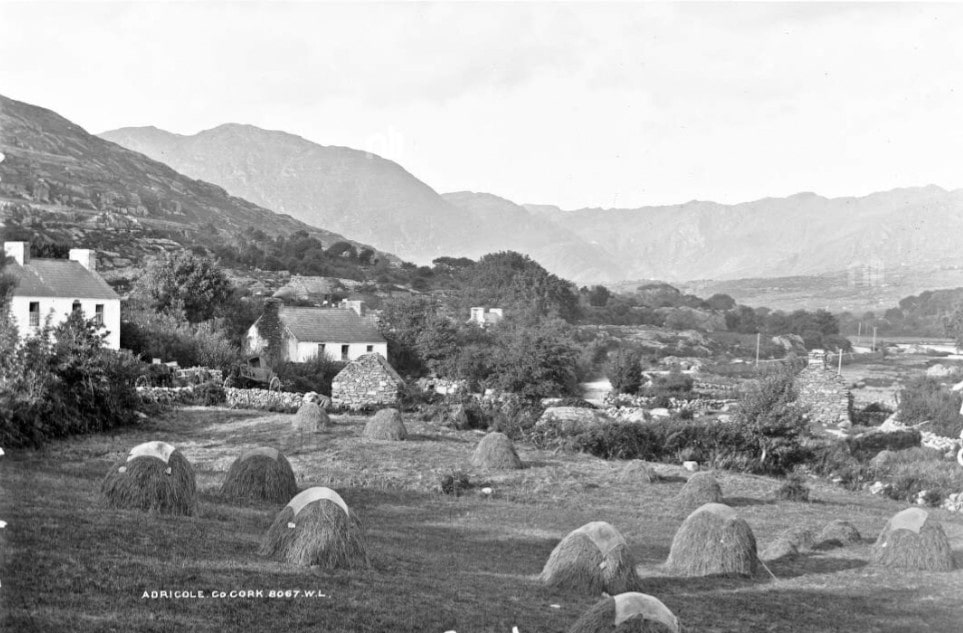

After Christmas, Easter was and is the most important Church festival in Ireland. As at Christmas, tradition demanded that the dwelling house, the outhouses and the farmyard should be set in order before Easter. The home was swept and cleaned, the walls were whitewashed, the furniture scrubbed clean. The cowbyre, the stable and other outhouses were swept and tidied. To the best of their means, people bought new clothes at this time, which were shown off by the proud owners at church on Easter Sunday. The Easter season was also seen as the occasion for the first outing for new clothes and a beautiful new Easter bonnet.

Good Friday was a day of austerity, a day of ‘black fast’. Many people ate nothing until midday; even then, some took no more than three mouthfuls of bread and three sips of water. No nails were driven into timber on Good Friday out of respect for Christ’s death and women would let their hair hang loose as a sign of sorrow. Nobody would move house or begin any important enterprise on this day. No blood should be shed, so no animals or bird would be slaughtered. Between midday and three o’clock, traditionally the period when Christ hung on the cross, silence was observed as far as possible.

On the islands and in the coastal areas of West Cork most people collected shellfish on the strands – periwinkles, cockles, mussels, limpets. This was called the ‘cnuasach trá’, the strand gathering. Since meat was strictly forbidden, coastal people ate ‘bia trá’ (shore food).

It was considered a great blessing for an ailing person to die on Good Friday. A child born on Good Friday and baptised on Easter Sunday was expected to have the gift of healing.

In medieval times, the sun was seen as a symbol for Christ, ‘the true light of the world’, and a superstition spread throughout the Christian world that on Easter morning the sun danced in the sky with joy at the Resurrection. The sun’s image does indeed shimmer on many spring mornings due to the mingling of hot and cold air at the earth’s surface.

The Orkney Island writer, George Mackay Brown, writes about children going from house to house where they got presents of ‘Pace’ eggs. The word Pace is a variation of ‘Pasch’, an old name for Easter. Christ is often called the Paschal Lamb. The association of eggs with Easter is familiar to us all, especially in recent times in its modern commercialised form of the sale of chocolate Easter eggs. This springs from the old custom of eating hen eggs on Easter Sunday morning. In former times it is told that the people, after their breakfast of Easter eggs, decorated the trees with the shells, as blossoms, in honour of the occasion.

The origin of the Easter egg customs is probably derived from the fact that formerly during Lent people abstained from eggs and all animal products. So there would be a large accumulation of eggs by the coming of Easter, which provided a surplus for feasting, presents, games and so on. The general feeling was that ‘nobody should be without an egg at Easter’ and most farmer’s wives gave presents of eggs to their workers and poorer neighbours and no tramp or beggar was denied an egg at Easter. Mothers often added a little colouring matter, such as washing blue or onion skins, to the water in which the eggs were boiled, so that the children got theirs attractively coloured, or drew patterns and decorations on the egg shells. There was a time in Ireland when duck eggs would be eaten in large quantities on Easter Sunday and there was often a competition to see who could eat the most.

Children often had their own Easter parties with the eggs they gathered, supplemented by other ‘goodies’, cakes, sweets, and so on. They retired to a quiet place where they built a ‘house’ or fireplace to cook the eggs. This custom was known as the ‘clúideog’, a term which could mean the custom, the collected eggs or the place where they were cooked.

In the Irish of West Cork, there are at least two ‘seanfhocal’ (old sayings) referring to Easter: ’Bia is deoch I gcomhair na Nollag, éadach nua i gcomhair na Cásca’ – Food and drink for Christmas, new clothes for Easter. And also: ‘Bia glan na Nollag agus ‘éadach glan na Cásca’ – good food for Christmas and new clothes for Easter.

The Easter Sunday dinner was a festive meal, second in importance only to that on Christmas day. All who could afford it ate meat, roast lamb being a traditional favourite. Better-off farmers killed an animal for the festival and sent presents of portions to friends and neighbours. Often the animal had been slaughtered in November and salted down; special joints of this graced the farmhouse on festive days. Irish people often had ‘corned beef and cabbage’ as festive fare and this custom was brought by them to America.

When Christianity came to Ireland, the symbol of the hare was used deliberately to transfer old pagan religion into a Christian context, especially at Easter. As harbingers of spring, hares were held in high esteem. Over time the hare became the Easter rabbit or Easter bunny.

Easter is a time of joy and hope, with lengthening days and brightening weather. It was even more joyous in former times as it followed the austerity of Lent when no jollification was allowed. One pastime beloved by young and old was dancing, a community outdoor affair when weather permitted and there were few parishes in which an outdoor dance was not held on the evening of Easter Sunday.

Outdoor dancing on Summer Sunday evenings on concrete platforms was very popular in West Cork up to the 1960s. The Easter Sunday dance often included a contest for which a large cake was the prize, probably because the dance held on the day was almost always the first in the year.

Many holy wells, especially those named ‘Tobar Rí an Domhnaigh’ or ‘Sunday’s Well’, were visited on Easter Sunday and water taken from them on this day was believed to have more than usual curative powers.

Easter Monday was a favourite day for fairs and markets, at which there were not only buying and selling of livestock and merchandise but also games and sports, sideshows, dancing, eating and drinking, gambling, and faction-fighting. Horse-racing is also popular on that day – the Irish Grand National at Fairyhouse being the most important.

Easter Monday will always be remembered in Ireland as the day of the ‘Easter Rising’ in 1916. Yeats, in ‘Easter, 1916’, immortalised our patriots in verse:

‘And what if excess of love / bewildered them till they died? / I write it out in verse / MacDonagh and MacBride / And Connolly and Pearse / Now and in time to be, / Wherever green is worn, / All changed, changed utterly / A terrible beauty is born’.