In part one of a two-part article, Kieran Doyle introduces us to one of the world’s most savage civil wars. While Irish society remained democratic after its civil war, the Russian people still know repression today.

I want to begin by congratulating the organisers and contributors who took part in the Michael Collins Centenary celebrations, as well as those who ran and took part in the Bandon Walled Town Festival, that ran parallel to each other at the end of August. Both festivals showcased historical lectures and events, as well as family fun activities. Behind the thrills and frills and the serious business, are the hardworking committee members and organisations, who deserve great credit for making West Cork the place it is, (along with all the other community festivals this summer).

On the theme of civil war, It was fantastic in my opinion to see the leader of Fianna Fail and Fine Gael share a stage at the Béal na Bláth centenary commemoration. It reflected a maturity in our society, which has been long overdue. People often talk about the bitterness of the Irish civil war and its generational divide. Yet if you look at the historical record, it’s hard to understand why the wounds were not healed a long time ago when you put the Irish conflict in context with other European civil wars, which were far more savage, extreme and longer. The Spanish civil war left 100,000 ‘disappeared’, who are still unaccounted for, to this day. The Finnish civil war, a contemporary conflict of Irish civil war, was more brutal and bloodier ours. But the Russian civil war from about 1919 to 1921, was the most savage of any. It is estimated up to 12 million Russians perished in the most vicious manner. Context is everything and, in fairness, most students and adults are never exposed to the writings and histories of the aforementioned foreign conflicts, so we tend to imagine what happened here in Ireland as being the worst.

The aftermath of the Irish civil war amounted to our politicians shouting nasty things at each other or some refusing to take their seats in the Dáil, and hereditary grudges passed on like a baton in a relay. In spite of these seemingly ‘irreconcilable’ differences, Irish society remained democratic, with a free press, an unfettered and independent judicial system. It was far from perfect, as we have seen from the darker side of our history, but there was space to grow, which has led over time to the evolution of the country. We are currently the 15th oldest standing democracy in the world, since our civil war.

In contrast, when the Russian civil war ended in 1921, during the next seventy years, common Russian/Soviet men and women were subjected to an oppressive regime, which denied their citizens freedom of speech, freedom of movement, fairness under the law. The Cheka, and its descendant, the KGB, kept its citizens in terror. The judicial system was there to uphold the regimes politic indoctrination. Even after the fall of communism in 1991, Russian society has only superficially come of age, with an increased level of economic prosperity. Yet their politics, policing, press, and education have remained in the control of state influence, that has kept the common Russian man and woman in metaphorical chains. Meanwhile they have little to no freedom to change leaders or a system that claims to represent them with their increasingly hostile foreign policy.

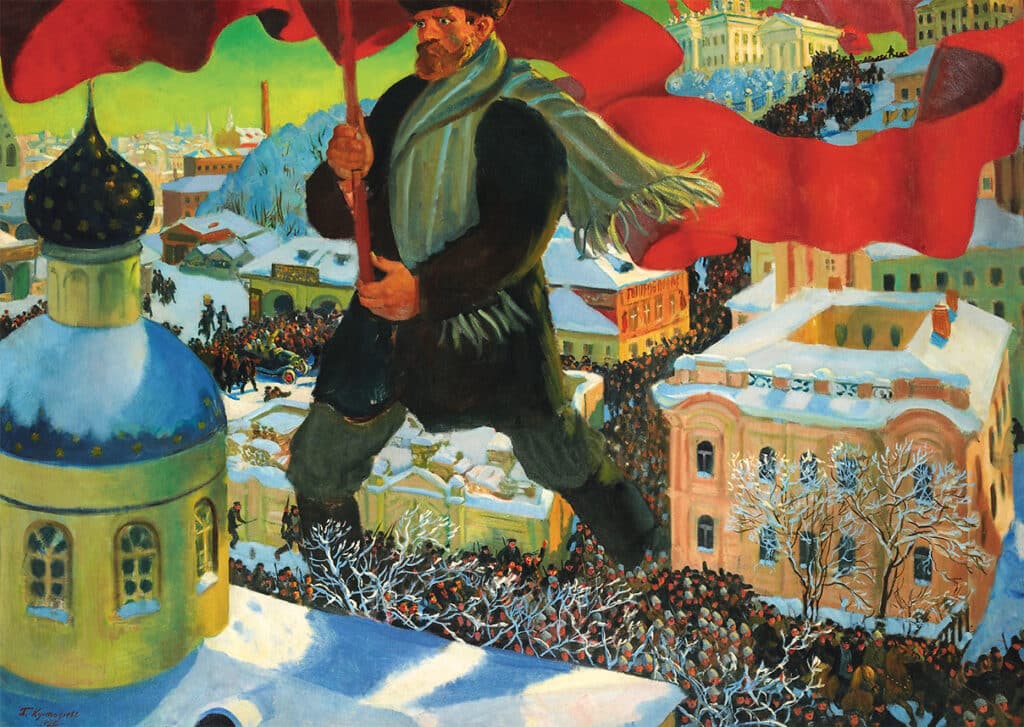

Considering the history of Russia, one of the things that has always gripped my imagination, is the evolution of communism as a form of governance. At the end of World War One, the great powers’ aristocrats and moneyed began to lose a grip on their power and the masses of people finally wanted a say in their own destiny. Indeed up to 1914, there were only ten democracies currently in existence. It wasn’t as if democracy was a ‘given’. The end of the Great War led to the rise of nationalism in places like Ireland, the popularity of working class political parties such as Labour in the United Kingdom, the dismantling of monarchy’s in places like Germany and Austria and of course the rise of communism as a political reality, first envisaged in the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engle’s in 1848. Communists in Russia initially sought to give the peasantry control over their own land, dismantle the Tsar and the aristocracy, which had bled and suppressed the people, and create a political system that was no longer dominated by class.The best book I read over the summer was Anthony Beevor’s ‘Russia: Revolution and Civil war 1917-23’. It was a forensic account of these conflicts. Beevor shows however, that the communist model envisaged by Marx and Engles, was choked at birth. Vladimir Lenin never had any intention of creating a socialist society, that the early months of the Russian revolution had promised. Together with his inner circle, including Trotsky and Stalin, had their designs on dictatorship, control and terror. In the first phase of the Russian revolution, Lenin and the communists broke free from the chains of the tsarist imperialist regime, with the support of the common man and woman. The horror that followed in their civil war, paled into existence compared what people had endured under their aristocratic jailers.

So where does one begin explaining the Russian civil war? It was dubbed a proxy World War. Because it was a war of ideology [initially], it cannot be categorised or defined easily, by national identity. On the side, was Lenin’s ‘Red’ communists, what we call Bolsheviks. They amalgamated a force from an eclectic mix of indigenous Red Guards [mainly built from the ranks of the industrial working force] Latvian Rifleman, Chinese recruits, Baltic sailors, released German prisoner of wars, with communist sympathies and even conscripted Tsarist officers who had no choice but to fight with them or die.

While you try to digest this, consider the opposition. This melting pot of groupings was an equally bewitching concoction. Collectively called the ‘Whites’, they were not ideologically aligned and even had opposing interests and political goals. Their only common objective was simply to stop the spread of Bolshevism. The Whites also contained communists, labelled Mensheviks who believed in socialism and a constitutional political assembly. They were paradoxically fighting with Tsarist officers and aristocrats who wanted to turn the clock back to the old regime. There were British, Allied and American troops, though small numbers, who were there to hinder the tentacles of communism’s global spread. [Who would have thought that, in 1919, Communism would become a global phenomenon] In this orgy of alliances there were also nationalist groups who, having gained independence from the collapse of the Russian empire, now did not want to be subsumed by the tentacles of the new Soviet Union either. Ukrainians, Finnish, and Polish troops, as well as soldiers from the Baltic States, rallied against the Bolsheviks [though each of those countries had communist supporters too, who wanted the Reds to succeed]. Also in the alliance were Cossacks from the semi-autonomous Steppes regions whom the Bolsheviks wanted to eliminate as class enemies. Looming menacingly in the Far East, were Japanese troops who had designs on the imperialistic empire, one that would play out fully in World War Two. Despite this vast rainbow coalition of collective power in the White corner, it doesn’t take an analytical genius to foresee that such disunity and paradoxically opposed ideologies would never unite to beat the Red wave of communism and its ideological unified and driven allies.

But you don’t win a war simply because the other side is simply disorganised. Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin knew the best way to win the civil war was brute savagery and they unleashed a hell on their own people to make sure they would be the ultimate victors. In next month’s article I want to explore the Russian Civil war in more detail. What will surprise many readers, is the role the Ukraine played too. When reading Beevor’s book, the parts relating to Ukraine were scarily like reading contemporary accounts of what is unfolding before our very eyes today. History is cyclical. Putin knows this only too well and we have often been informed in the media with his obsession to remould the old Russian empire. It is also a tale of the suppression of the common Russian people, who let’s face it, are still repressed today. I hope you will read part two in next month’s West Cork People, where I illuminate the horrors and crimes of a civil war like no other.